GMS Faculty Spotlight: Esther Bullitt, PhD

Esther Bullitt, PhD, is a professor of pharmacology, physiology & biophysics at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. She is the director of both the biophysics and physiology graduate programs within Graduate Medical Sciences.

Esther Bullitt, PhD, is a professor of pharmacology, physiology & biophysics at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. She is the director of both the biophysics and physiology graduate programs within Graduate Medical Sciences.

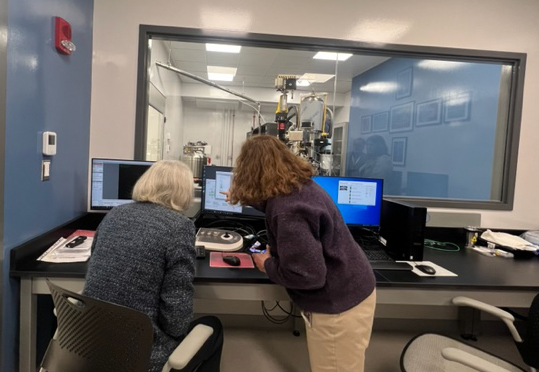

Dr. Bullitt was recently awarded a Shared Instrumentation Grant by the National Institutes of Health, which helped to fund BU’s new Cryo-EM Core Facility. The facility celebrated the “First Light” of its Glacios-2 cryogenic electron microscope (cryo-EM) in April 2024. The instrumentation allows investigators to determine structures of macromolecules at near-atomic resolution.

Graduate Medical Sciences spoke to Dr. Bullitt about her career at BU, the Shared Instrumentation Grant and the novelty of the new Cryo-EM facility. Learn more below:

Can you tell me a bit about your journey to Boston University?

I graduated from college and said I was never going to school ever again. I worked in the aerospace industry for a couple of years. I decided that wasn’t the right path and that I wanted to do something more biological and more biomedically relevant, so I went back to graduate school.

I have a PhD in biophysics. I’m working on macromolecular structures, complex things that are important for biomedical purposes. I originally worked on actin, one of the muscle proteins, and then switched as a postdoc. I was actually a postdoc in the BU physics department on the Charles River Campus and worked on bacterial adhesion, which is something that is still my primary research.

Can you tell me a bit more about your research?

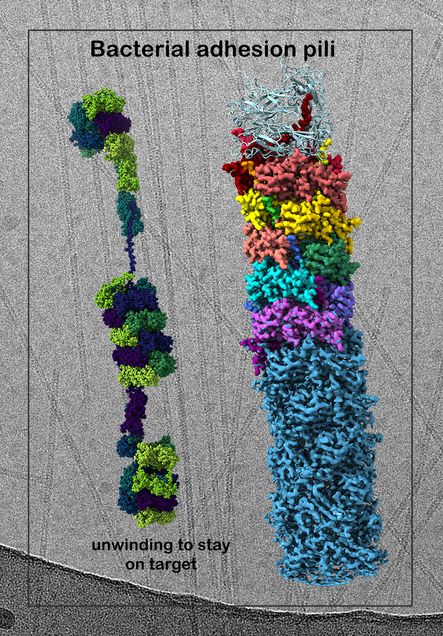

Bacteria have these very thin filaments on their surface that are helical. These helical filaments can unwind and rewind, because that reduces the force at the tip. So, it gives them the ability to stay bound during, for example, fluid flow events in the gut.

These days, I study mostly traveler’s diarrhea bacteria, but I’ve also worked on urinary tract ones and ones that cause respiratory infections. In traveler’s diarrhea, in your digestive tract, there’s peristalsis and there’s a lot of forces going on. Instead of being like uncooked spaghetti, where it would break, it’s more like a slinky and it unwinds. Then, when the force goes away, it rewinds. I study those structures in order to figure out how they work and find ways to make them not work.

What drew you to working at BU?

BU is the most collegial place I’ve ever worked. I’ve been places where people feel like their success has to come at the expense of someone else’s. At BU, I feel like anyone’s success is everyone’s success, and that’s such a different and refreshing attitude that I have stayed.

Can you tell me about your mentorship role at GMS?

I’m the director of both the biophysics and physiology programs. It’s great to be able to help [graduate students] figure out what their plans are and how to succeed at BU. Sometimes, a student comes in with a plan, and when you talk to them about it, they decide, “Maybe that isn’t really what is going to make me happy and successful.” So, you see them evolve over time. It’s really quite wonderful.

Can you tell me about the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant you received and its application to the new Cryo-EM Core Facility?

For an NIH Shared Instrumentation grant, you need to have a large group of scientists and show that you really need this instrumentation to support a lot of significant research at the University. We got together a group of 25 investigators who are interested in using the Cryo-EM Core Facility to learn about their biomedical structures and macromolecular assemblies, so that they can advance their research. It’s a very broad range of departments on both campuses. There are people from chemistry, from biomedical engineering, from the dental school, as well as from the medical campus.

The instrumentation that we have is wonderful and functional, but one of our electron microscopes is over 20 years old. The other is over 30 years old. What we were aiming for is to bring us up to the 21st century and to be able to look at structures at near-atomic resolution. That’s an order of magnitude better than what we are currently able to do. So, I wrote the grant proposal with these 25 investigators, and we received the funding for it.

What we requested was for the low end of the new microscopes, which was going to be great and easy to use. However, our department chair decided to invest in cryo-electron microscopy. So, with department and university support we’ve been able to buy a fantastic microscope that does near-atomic resolution. The one that we were going to buy was semi-automated, but the one that we have bought is fully automated, which means it can run 24/7. You can use half of a day to decide exactly which are your best samples and which ones you want to do automated collection on, then overnight, it just takes care of everything. There’s a workflow in which you simply tell it, “This is the best sample,” and at the other end, you see the beginning reconstruction of your sample. It’s just amazing.

Can you expand on the novelty of the device and how it’s different from what you had before?

A car has all these parts that make it run properly. It’s the same thing with bacteria, viruses, and human beings. To figure out how it works, we look at the pieces. If you can determine their structures at high enough resolution, then you can learn a lot about how it works. What we do is we take the sample, and we freeze it so quickly in liquid nitrogen-cooled liquid ethane so that the buffer freezes as a glass. If you think about the water in your ice cube tray, it freezes as a crystal. All those sharp points would both get in the way of the pictures and jab into your sample and ruin it. So, we’re freezing it so quickly that we have the object preserved in essentially a glass.

When you take pictures of the sample, it’s in a really close to native state. It’s very much like where it was in the cell or where it was on the bacterium. In an electron microscope, when you take a picture, the sample is moving just a little bit. These new microscopes take a series of pictures and then use a computer to realign them and get one perfect picture back. That is totally not possible in the old microscopes.

We can take 500 pictures an hour now. In the old microscope, if you were lucky, you could take 200 pictures in a day. You had to do it all manually. So, it’s a totally different order of magnitude of what you’re able to do and the data you’re able to collect. The more data you can collect, the more pictures of your object you can average together to get the best structural information. We have a workstation that can do a lot of this work, then we use the BU supercomputer to analyze all these thousands of pictures. Up until this point, those of us that have done high resolution structures have always had to go elsewhere to collect our data. We couldn’t collect our data at home, and now we can, which is huge.

Can you share more about the facility’s staffing and use by various BU departments?

We’ve been able to hire a Cryo-EM Scientist, Chad Hicks, PhD, to run the facility and assist people. He is fantastic. He just received his PhD from Johns Hopkins, and we are so lucky to have him. He came a week before the microscope arrived, and so he’s gotten to do everything. Chad is able to help coordinate all this interdisciplinary research and cross-campus collaboration. I would say two-thirds of the people who are planning to use this microscope have no experience with this, so this will be a totally new and wonderful thing for them to be able to add to their science toolkit.

The university has been unbelievably supportive. We have the ability to charge extremely low rates for three years, so that gives people enough time to write grants in order to be able to pay the full costs later on. People can try it with a very reasonable cost input. They can try it and see if it works for what they want to learn.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.