Trauma Case 1: Stab to Left Chest

Boston Medical Center – Trauma Case of the Month

Case #1: Diagnostic Laparoscopy in Penetrating Chest Trauma

by Rie Aihara, M.D. and Wayne LaMorte, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H.

Pre-Hospital Data

A 17 year-old male from Michigan was visiting his cousins and friends in Boston, when he became a victim of a stabbing. This all began when the victim confronted an old friend about a personal conflict which occurred between them years ago. What started out as a verbal argument eventually resulted in physical violence. The victim sustained a single stab wound to the left chest in the mid axillary line, just below the level of the nipple. He was transported to our emergency department by Boston EMS. He was noted to be awake and alert throughout the entire transport.

Past Medical/Surgical History: Asthma

Family History: Non-significant

Medications: Inhalers as needed

Allergy: No Known Drug Allergy (NKDA)

Trauma Room Assessment:

The patient was moved from the stretcher onto the examination table, and the only complaint obtained from the patient was shortness of breath.

Cardiac monitors, blood pressure-cuff and oxygen saturation probes were then placed on the patient.

Vital signs:

Heart rate- 90/min

Blood Pressure- 130/70

Respiratory rate 25

Temperature- 97 F

Primary Survey:

Airway- patent airway as demonstrated by his ability to talk.

Breathing- decreased breath sounds at the left base.

- Oxygen mask with 100% FiO2 was placed; & an oxygen saturation of 100% was obtained

Circulation – no active external bleeding

Deficits – neurological exam grossly intact

Exposure – the patient’s clothes were removed to throughly examine for other injuries

Secondary survey:

HEENT: no lacerations, no hematomas, no fractures palpated

Neck: midline trachea, no JVD, no crepitus

Chest: clear on right, single stab wound to the left chest in the mid-axillary line in the 4th intercostal space, no crepitus, no bleeding, decreased breath sounds at the left base

Cardiac: regular rate and rhythm (RRR), normal S1 and S2

Abdomen: present bowel sounds, soft, non-tender, non-distended

Extremities: warm, present distal pulses

Neuro: awake, GCS 15, no focal deficits

Radiological Survey:

Chest X-ray: left sided hemopneumothorax

- An upright CXR was obtained. We were able to sit the patient up because he had an isolated penetrating injury to the chest, and the mechanism of injury did not warrant spinal precautions. A pelvis and lateral C-spine films were also not obtained because of the isolated nature of the injury.

Other Pertinent Studies:

Transthoracic Echocardiogram: no pericardial effusion

- Because the weapon can be aimed at any direction (medially, superiorly, inferiorly), the heart can be potentially injured. A pericardial tamponade is lethal unless discovered and treated quickly.

Blood Work Ordered:

- Type and screen

- Coagulation panel

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Arterial blood gas

- Toxicology screen

Blood typing is essential because the patient may need transfusions and possibly surgery. The coagulation panel and CBC will be helpful as baseline and to see if other factors such as plasma may be required. Note that the hematocrit is not going to reflect the amount of bleeding this patient may have because the hematocrit is a percentage of red blood cells in the blood. When a trauma victim bleeds, the shed blood is whole blood (both red cells and plasma) which has the same hematocrit as the intravascular blood. It is only after the movement of interstitial fluid into the vascular space in an attempt to increase the total volume does the hematocrit drop from dilution. The arterial blood gas is an important indicator of blood loss, therefore hypoperfusion, resulting in metabolic acidosis (decreased bicarbonate).

ER Procedures:

Chest tube placement: drained 300cc of frank blood

Change in status:

The patient at this time began complaining of a new subscapular pain, or pain between the shoulder blades. This was alarming to the trauma team for the following reasons.

- Patients with diaphragmatic injuries and irritation from the blood frequently exhibit referred pain in this distribution. If the knife wound had projected inferiorly penetrating the diaphragm, there was also a high likelihood of intraabdominal injuries. Therefore, it was decided that the patient required surgical exploration, and the patient was taken to the operating room.

Operating Room:

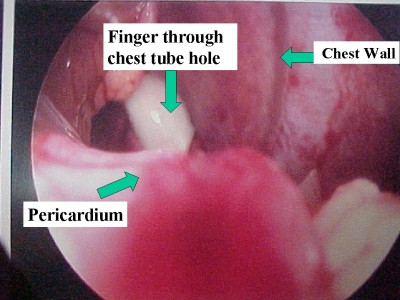

The surgical team performed a diagnostic laparoscopy in order to determine whether or not the diaphragm had been penetrated. The laparoscopy demonstrated an obvious defect in the diaphragm, as shown here.

Inspection within the abdomen demonstrated blood clots on the anterior surface of the stomach and the left lateral segment of the liver. In order to more carefully assess the extent of intra-abdominal injuries and carry out repair, the procedure was converted to an open laparotomy.

Upon exploration, there were three lacerations on the surface of the liver which required suture closure. There was also a 2 cm perforation of the anterior surface of the stomach which was closed primarily in two layers.

In order to assess the extent of intrathoracic injuries more closely, the laparoscope was advanced from the abdomen into the thorax through the diaphragmatic defect.

Examination of the pericardium showed no evidence of bleeding, contusion, or penetration.

We therefore proceeded to close the diaphragmatic perforation with interrupted Ethibond suture with pledgets.

Upon completion of the procedure the patient recovered without complications and was discharged to home in four days.

Major Teaching Points:

- Arterial blood gas is a better indicator of hemorrhage than hematocrit for the reasons described above.

- The peritoneal cavity can extend into the thoracic cavity as high as the 4th intercostal space. Any penetrating chest injury at or below that level has the potential to injure intra-abdominal organs.

- The presence of subscapular pain in a patient with a penetrating injury to the chest strongly suggests penetration of the diaphragm and a high risk of associated intra-abdominal injuries. This situation warrants surgical evaluation of the abdomen in the operating room.

Surgical exploration can be undertaken in one of two ways: a) the conventional approach is to perform an open laparotomy, and b) the alternate approach is to do a diagnostic laparoscopy. The primary purpose of the laparoscopy is to determine the presence of diaphragmatic perforation. If the diaphragm is intact, then there should be no intra-abdominal injuries. In this case, a midline incision can be avoided, and the recovery period will be shortened significantly. This can be beneficial to high risk patients such as those with pulmonary disease, cardiac disease and morbid obesity where a long midline incision can be a source of morbidity such as infection and respiratory compromise