Research Week 2022 – Faiz Khan, MD, ScM

| TITLE: Cancer, not COVID: Juvenile granulosa cell tumor presenting with fever and elevated inflammatory markers after initially suspected COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AUTHORS (FIRST NAME, LAST NAME): Faiz Khan1, Swati Patel Varshney2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| INSTITUTIONS (ALL): 1. Internal Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, United States. 2. Infectious Diseases, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, United States. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

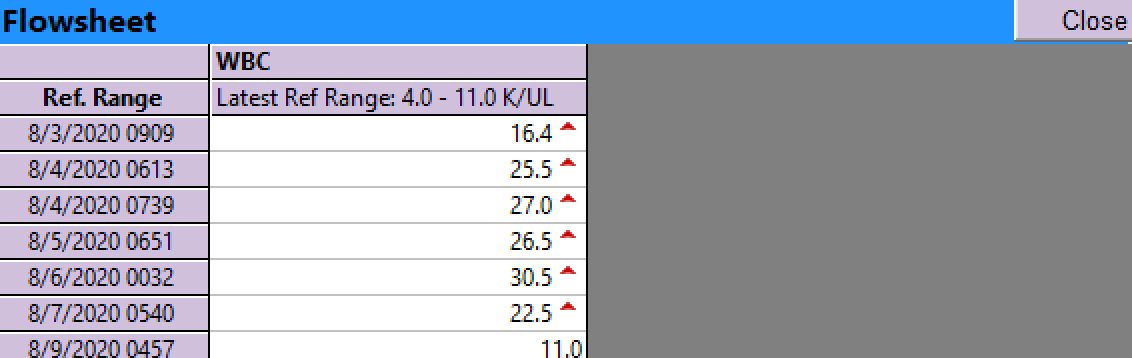

| ABSTRACT BODY: Learning Objective 1: Recognize malignancy as a cause of unexplained fever and elevated inflammatory markers in patients initially suspected to have COVID-19 infection. Learning Objective 2: Assess the role of imaging in evaluation of unexplained fever and elevated inflammatory markers. Case: A 23 year old female with a history of remote intravenous heroin use presented to the emergency department with one week of fevers, pleuritic chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting. Prior to the onset of her symptoms she had been working as a nursing assistant in a group home. She denied family history of malignancy or rheumatologic disease.At admission she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypoxic requiring 2L of nasal cannula. Her laboratory testing was notable for a leukocytosis of 16.4 K/uL with neutrophilic predominance and lymphopenia, ESR 123 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) 292.5 mg/L, fibrinogen >800 mg/dL, ferritin 332 ng/mL, D-dimer 305 ng/mL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 325 U/L and procalcitonin 0.90 ng/mL. SARS-COV-2 nasopharyngeal swab was negative. Chest X-Ray revealed new bilateral pleural effusions. Computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram was negative for pulmonary embolism. She was admitted to the COVID-19 service for ongoing suspicion of COVID-19 infection, despite initial negative testing.

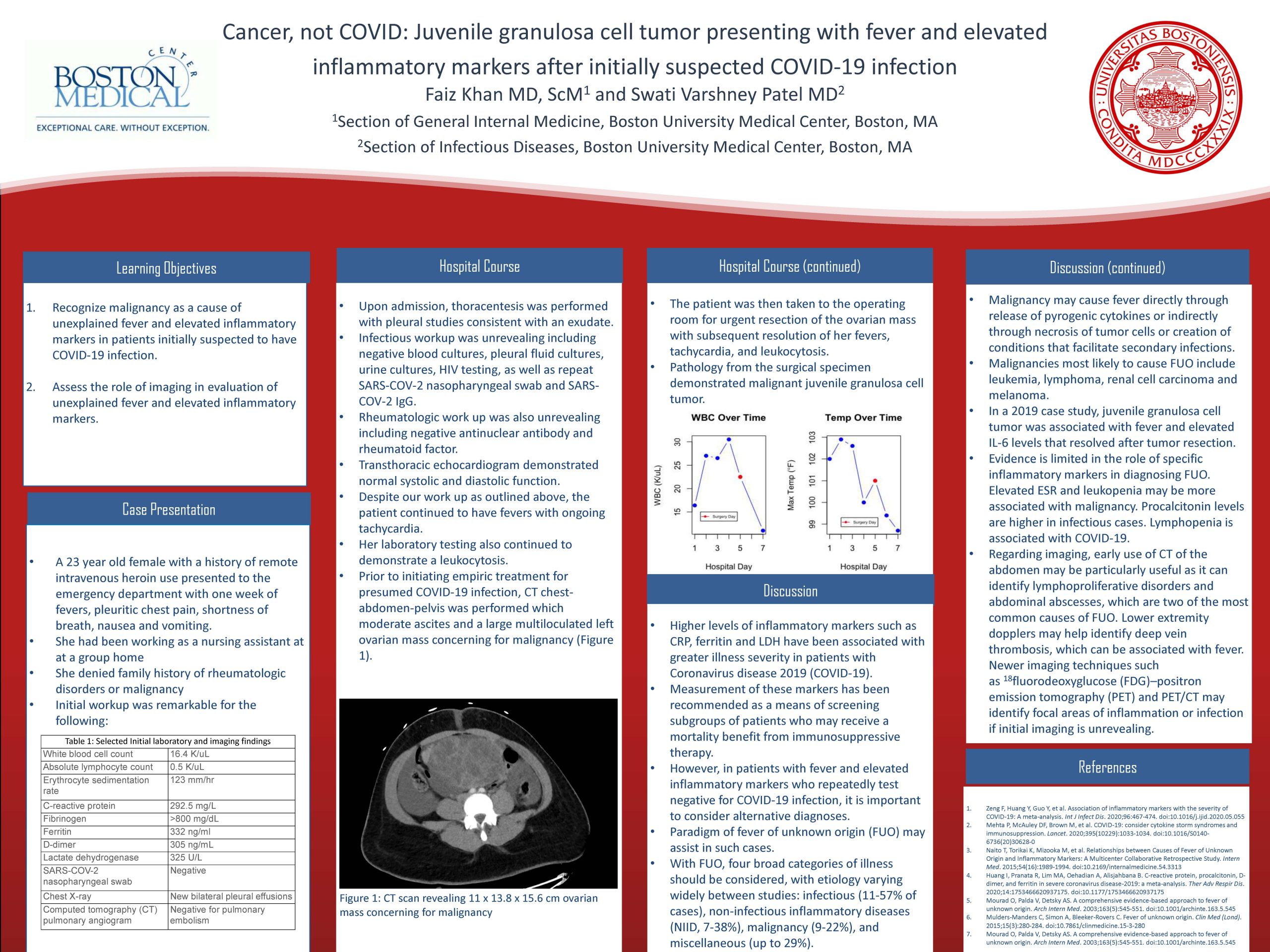

Upon admission, thoracentesis was performed with pleural studies consistent with an exudate. Infectious workup was unrevealing including negative blood cultures, pleural fluid cultures, urine cultures, HIV testing, as well as repeat SARS-COV-2 nasopharyngeal swab and SARS-COV-2 IgG. Rheumatologic work up was also unrevealing including negative antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated normal systolic and diastolic function. Despite our work up as outlined above, the patient continued to have fevers with ongoing tachycardia. Her laboratory testing also continued to demonstrate a leukocytosis. Prior to initiating empiric treatment for presumed COVID-19 infection, CT chest-abdomen-pelvis was performed which revealed moderate ascites and a 11 x 13.8 x 15.6 cm multiloculated left ovarian mass concerning for malignancy. The patient was then taken to the operating room for urgent resection of the ovarian mass with subsequent resolution of her fevers, tachycardia, and leukocytosis. Pathology from the surgical specimen demonstrated malignant juvenile granulosa cell tumor. Review of the literature regarding fever of unknown origin (FUO) may assist in such cases. FUO is defined as a temperature of >100.9oF recorded several times over three weeks despite at least 3 outpatient visits, 3 inpatient days or 1 week of invasive outpatient investigation. Four broad categories of illness should be considered, with etiology varying widely between studies: infectious (11-57% of cases), non-infectious inflammatory diseases (NIID, 7-38%), malignancy (9-22%), and miscellaneous (up to 29%). Malignancy may cause fever directly through release of pyrogenic cytokines or indirectly through necrosis of tumor cells or creation of conditions that facilitate secondary infections. Malignancies most likely to cause FUO include leukemia, lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma and melanoma. In a 2019 case study, juvenile granulosa cell tumor was associated with fever and elevated IL-6 levels that resolved after tumor resection. Evidence is limited in the role of specific inflammatory markers in diagnosing FUO. In a retrospective study of FUO in 121 patients, all 13 patients with malignancy had an ESR>40 mm/hr. Leukopenia was more associated with malignant causes of FUO. Another retrospective study found ferritin levels were higher in patients with non-infectious causes, while procalcitonin levels were higher in patients with infectious causes. Lymphopenia is found in as many as 83% of patients with COVID-19 (CDC), though specificity is unclear. Various algorithms include the use of imaging to help diagnose FUO. Of evidence-based modalities, CT of the abdomen may be particularly useful early in investigation as it can identify lymphoproliferative disorders and abdominal abscesses, which are two of the most common causes of FUO. Lower extremity dopplers may help identify deep vein thrombosis, which can be associated with fever. Newer imaging techniques such as 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–positron emission tomography (PET) and PET/CT may identify focal areas of inflammation or infection if initial imaging is unrevealing. |