To Isolate or Not? Diagnosing and Managing Mumps

Joan Savage, MD

Learning objectives:

- Diagnose mumps through PCR of a buccal or nasopharyngeal swab or urine sample and through mumps serum IgM and IgG testing.

- Recognize a patient at risk of transmitting mumps and manage his or her isolation status accordingly.

Case:

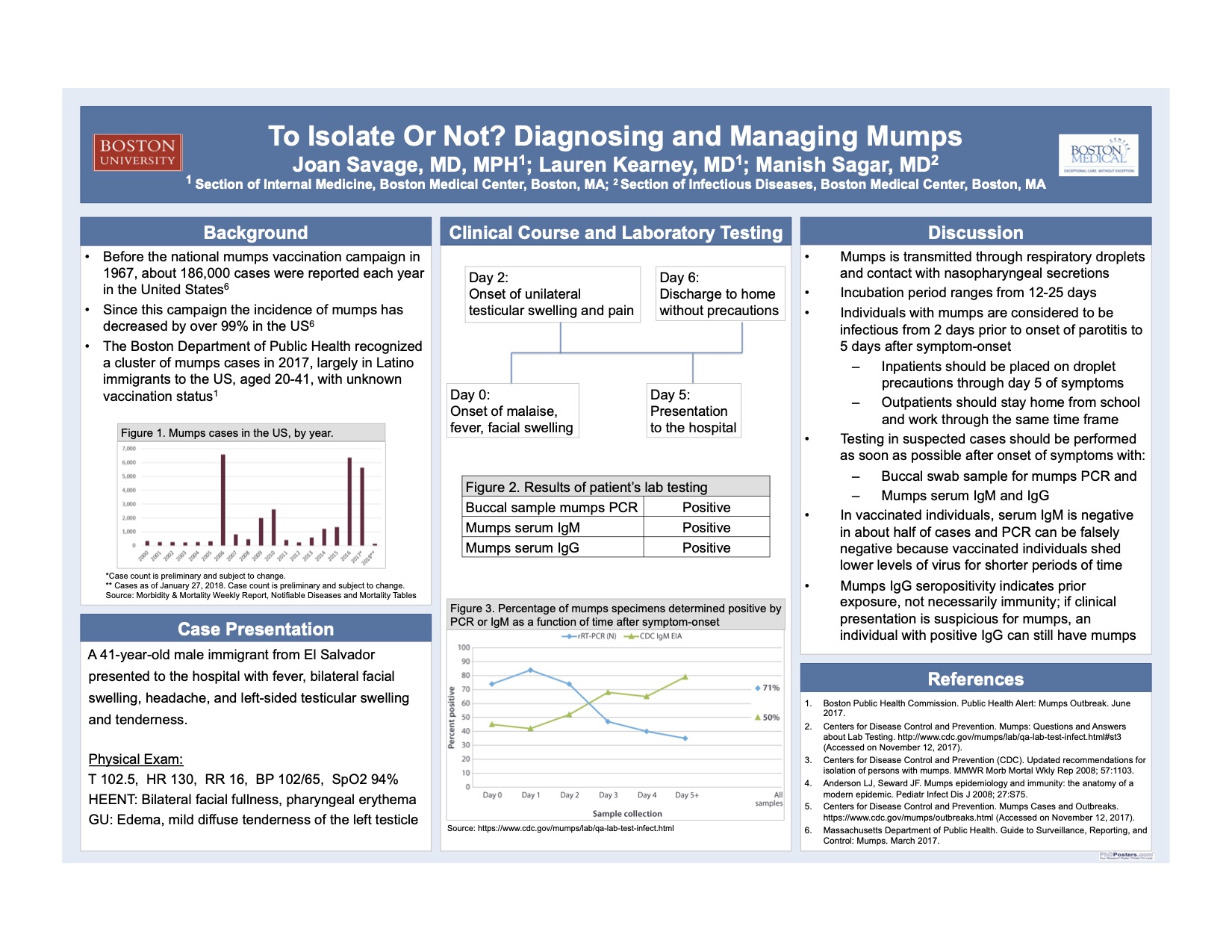

A 41-year-old male presented to the emergency department with fever, bilateral facial swelling, headache, and left-sided testicular swelling and tenderness. He immigrated to the United States from El Salvador 19 years ago. His vaccination status is unknown. Six days prior to presentation, his symptoms began with malaise, low-grade fever, chills, and facial swelling. Three days later, he developed left-sided testicular swelling and pain. He reported no neck pain, photophobia, phonophobia, confusion, difficulty swallowing, voice changes, recent travel, or known sick contacts.

On examination, the patient was febrile to 102.5, with a pulse of 130, blood pressure of 102/65, respiratory rate of 16, and a SpO2 of 94% on room air. He had bilateral facial swelling, pharyngeal erythema and edema with no exudates, normal heart and lung sounds, and left testicular edema with mild diffuse tenderness to palpation. He did not exhibit nuchal rigidity, and had no focal neurological deficits or skin rashes.

Buccal PCR, serum IgM, and IgG were all positive for mumps, indicating active mumps infection. Additional testing for mononucleosis, pharyngeal streptococcus, respiratory viruses, HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, urinary tract infection, and bacteremia were all negative. Testicular ultrasound was consistent with left-sided orchitis.

The patient was admitted for symptomatic management of mumps infection and discharged to home without isolation precautions two days later.

Discussion:

Before the mumps vaccination campaign in 1967, about 186,000 cases were reported each year in the United States. Since that initial campaign, incidence of mumps has decreased by over 99% in the US, with numbers of mumps cases ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand in any given year. While generally self-limited, serious complications of mumps can include meningitis, encephalitis, permanent hearing impairment, and pancreatitis, among others, and it is important to recognize and prevent the spread of the disease.

The Boston Department of Public Health has recognized a cluster of mumps cases in Boston in 2017. These cases have largely affected Latino individuals between ages 20 and 41 who have immigrated to the United States and have unknown vaccination status. Typically, mumps outbreaks have occurred in settings where prolonged close contact is common, even in populations with a relatively high level of vaccination, like in college dormitories; affected individuals in these circumstances are frequently evaluated in the same student health center, often leading to quicker diagnosis and isolation of patients.

Mumps is transmitted through respiratory droplets and direct contact with nasopharyngeal secretions. The incubation period ranges from 12-25 days. Individuals with mumps are considered to be infectious from 2 days prior to onset of parotitis to 5 days after symptom-onset. In the outpatient setting, recommendations are to stay home from school or work through day 5 of symptoms. Inpatients should be placed on droplet precautions during this time frame. Asymptomatic and mildly ill individuals may also spread the disease. Unvaccinated individuals who have had contact with a confirmed case of the mumps should also be advised to stay home from school or work during the incubation period.

Testing in suspected cases should be performed as soon as possible after the development of parotitis with PCR of a buccal sample. This is preferred compared to nasopharyngeal swabs and urine samples. Serum IgM and IgG for mumps should also be obtained. History of vaccination for mumps can pose a challenge in laboratory confirmation of mumps infection. Serum mumps IgM will be negative in about half of cases in vaccinated individuals and PCR can also be falsely negative as vaccinated individuals shed lower levels of virus for a shorter period of time. Mumps-specific IgG indicates prior exposure to mumps virus or vaccine, but does not necessarily indicate immunity.

- Boston Public Health Commission. Public Health Alert: Mumps Outbreak. June 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mumps: Questions and Answers about Lab Testing. http://www.cdc.gov/mumps/lab/qa-lab-test-infect.html#st3 (Accessed on November 12, 2017).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for isolation of persons with mumps. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57:1103.

- Anderson LJ, Seward JF. Mumps epidemiology and immunity: the anatomy of a modern epidemic. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27:S75.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mumps Cases and Outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/mumps/outbreaks.html (Accessed on November 12, 2017).

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Guide to Surveillance, Reporting, and Control: Mumps. March 2017.

5 comments

An important presentation in light of anti-vaccine movem,ent, and especially so in comparison with COVID-19

an extremely relevant piece of work in light of the current pandemic. i was also interested in the issue of the cluster in the Latinx community and the impact of disparities.

Nice work, Joan!

Joan, terrific report! Many important lessons from this case!! Well-done! Dave

Having had a fellow medical student with mumps orchitis and the risk of future sterility, the importance of vaccination, early recognition and isolation of cases really hit home. Important messages here. Thanks, david