Mental Illness Rulebook Gets a Rewrite: MED psychiatry chair gives revised DSM good prognosis

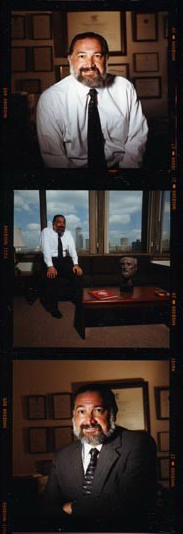

Domenic A. Ciraulo, MED chairman of psychiatry, says that for teachers, clinicians, and researchers in the fields of psychiatry and psychology, the DSM serves as a dictionary.

The 58-year-old bible of psychology and psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, best known as simply the DSM, recently released the much-anticipated proposed revisions for its upcoming fifth edition, with additions of new mental disorders and narrowing or expanding working definitions of others. The changes will resonate far beyond the mental health field, affecting not only physicians, therapists, patients, and their families, but health insurers, drug companies, teachers, and employers.

Domenic A. Ciraulo, MED chairman of psychiatry, says that for teachers, clinicians, and researchers in the fields of psychiatry and psychology, the DSM serves as a dictionary.

Domenic A. Ciraulo, MED chairman of psychiatry, says that for teachers, clinicians, and researchers in the fields of psychiatry and psychology, the DSM serves as a dictionary.

What seems at first glance a forbidding volume laden with technical jargon, the DSM is the gold standard for defining mental illness, and those definitions evolve to reflect changing societal norms, and more important than ever, scientific research. For example, it wasn’t until 1974 that homosexuality was removed from the manual, and academic debate still simmers over gender disturbances and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The complete revised edition won’t appear until 2013, but many of the proposed changes have already sparked debate. The new edition will, for example, broaden the definition of autism to include Asperger’s syndrome and relabel behaviors in young children that would currently be diagnosed as bipolar disorder. And the revised manual may include some newly coined disorders, such as “binge eating disorder” and “hypersexuality.”

What does the DSM’s fifth revision since 1952 reveal about the state of psychological and psychiatric treatment and research, and how might the changes affect us? BU Today spoke with Domenic Ciraulo, chair of the School of Medicine’s department of psychiatry and chief psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center, about the DSM, its significance, and a shift toward research-based diagnoses.

BU Today: How important is the DSM?

Ciraulo: The DSM is huge. It’s really how we describe our patients in talking with one another and in discussing treatment, which should be tied to the diagnosis. It’s very important, first of all, to recognize what is a mental disorder, and that’s what DSM V has attempted to do. It distinguishes mental disorders from expected changes such as grief when a spouse dies. If you think about DSM and what purpose it serves, for someone like me, a teacher, clinician, and researcher, it’s really a dictionary. So when I say, this person has a certain type of schizophrenia, we’re all talking about the same disorder. We at least need to know if a person presents with, say, depression, even though all clinicians are aware that these disorders are very heterogeneous and can have a much different prognosis. And DSM makes it easier for psychologists and psychiatrists around the world to communicate with each other.

What do you think about the proposed changes?

I’ll start with what they’ve done with addiction, which is my specialty area. I think they made some real progress by eliminating the term “dependence” for anything that isn’t physiological, with withdrawal symptoms. That’s important, because in the context of medical treatment people get physiologically dependent on lots of drugs. People with hypertension have withdrawal from beta-blockers, and they’re not addicted. Or someone with pain syndrome being treated with opiates, that isn’t the same as someone using heroin on the street. I think changing it to “addiction and related disorders” is a better, more general term, and allows people to consider if behaviors like gambling or even Internet use can be addictions.

When the revisions were publicized, there was a lot of news coverage about the proposed broadening of the definition of autism. Is this a good thing?

It makes sense. After examining the newer research data on autism, some terms will now be included in autism spectrum disorders. So Asperger’s syndrome, which has been a separate diagnosis because factors like language are often unimpaired, and a number of other autism-related disorders will now fall under that term.

Do medical insurers’ reliance on DSM-based diagnoses make it difficult for doctors when a patient’s disorder is a combination of problems?

Well, insurance generally gets in the way of me doing my job. I don’t think it’s related to DSM. They don’t have to pay for something because it’s in DSM; they can say they see it as a learning disorder. I’ll give you an example from this week. We were asked to do a neuropsychological evaluation on a college student with ADHD (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and what we got back from the insurance company was, we don’t pay for this because it’s not a psychiatric disorder, it’s an educational disorder, even though it’s in DSM IV. They make their own rules. Depression has been in DSM from the start, and many times my patients don’t get reimbursed for antidepressant medication.

Do DSM definitions have any effect on the stigma associated with many mental and behavioral disorders?

I think the stigma remains a big problem for psychiatric disorders, and I’m not sure any diagnostic system is going to help that. I think that most of the argument has been around gender identity issues; that’s a very controversial area. I think that in the end it’s going to be research that establishes a genetic and biological basis for the disorders we treat. And that will minimize the stigma attached to them. That being said, even though there’s a strong genetic component to alcoholism, there’s a lot of stigma.

How strong is the connection between DSM revisions and the R&D and marketing tactics of pharmaceutical companies?

Certainly, individual members of the DSM task force have received drug company support and revealed those conflicts to the American Psychological Association (APA), which oversees the appointment and consulting process. I think you’re quite right that it’s important for drug companies to go after the particular implications of new or different diagnoses. It happens already — if, say, Paxil is approved for depression, the drug company will try to get it approved for anxiety and PTSD. But there are reasons for this beyond greed and extending patents. It also protects doctors to some extent. Every time a physician prescribes something off-label, he or she is taking a chance. In Massachusetts it’s easier to support that choice with an explanation, but other states are not so lenient.

The proposed revisions include adding to the lexicon “temper dysregulation disorder with dysphoria” as an alternative to bipolar disorder, widely believed to be overdiagnosed. Can you explain?

Bipolar disorder in children is an issue that’s vigorously debated. It was rarely diagnosed in kids 30 years ago, but then it became common as a diagnosis combining temper outbursts with attention deficit. This new disorder will change treatment to some extent, discouraging doctors from immediately rushing in with certain drugs used for bipolar disease. However, if drugs are used, and the treatment focus is drug therapy, it would probably be the same type of drugs that were used before. The jury is still out on whether the new definition will be accepted; doctors may try more behavioral interventions before using things like lithium to control aggression, or anticonvulsants.

How is the DSM committee selected?

Some people lobby to be on the committee. The APA picks the lead group, and the lead group picks the working groups. Each of the subcommittees has well-known experts, for the most part. The actual process may be politically biased, but I think what happened with DSM V is there’s been a lot of openness; on their Web site they give you the opportunity to have input. In the past that wasn’t the case.

This BU Today story was written by Susan Seligson. She can be reached at sueselig@bu.edu.

View all posts