New Study Investigates How Diet May Slow Normal Brain Aging

As the brain ages, cells in the central nervous system experience metabolic dysfunction and increased oxidative damage. These cellular issues impair the ability to maintain the myelin sheath (the protective covering around nerve fibers), which leads to age-related white matter degradation. Microglia are the brain’s primary immune cells, and their activation is a normal response to injury or infection. In conditions like aging or Alzheimer’s, microglia can become chronically activated, leading to a harmful inflammatory state that damages neurons, but the exact reasons are not fully understood.

A new study from researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine has found that consuming 30% fewer calories than usual for more than 20 years, can slow down signs of aging in the brain. The study was done using an experimental model closely related to humans.

Ana Vitantonio

Ana Vitantonio“While calorie restriction is a well-established intervention that can slow biological aging and may reduce age-related metabolic alterations in shorter-lived experimental models, this study provides rare, long-term evidence that calorie restriction may also protect against brain aging in more complex species,” says corresponding author Ana Vitantonio, a fifth-year PhD student in the department of pharmacology, physiology & biophysics.

The study was initiated in the 1980’s in collaboration with the National Institute on Aging and included two groups of subjects. One group ate a normal, balanced diet, while the other group ate approximately 30% fewer calories. The main goal of the original study was to determine if eating fewer calories could extend their lifespan. The subjects lived out their natural lives; their brains were analyzed postmortem.

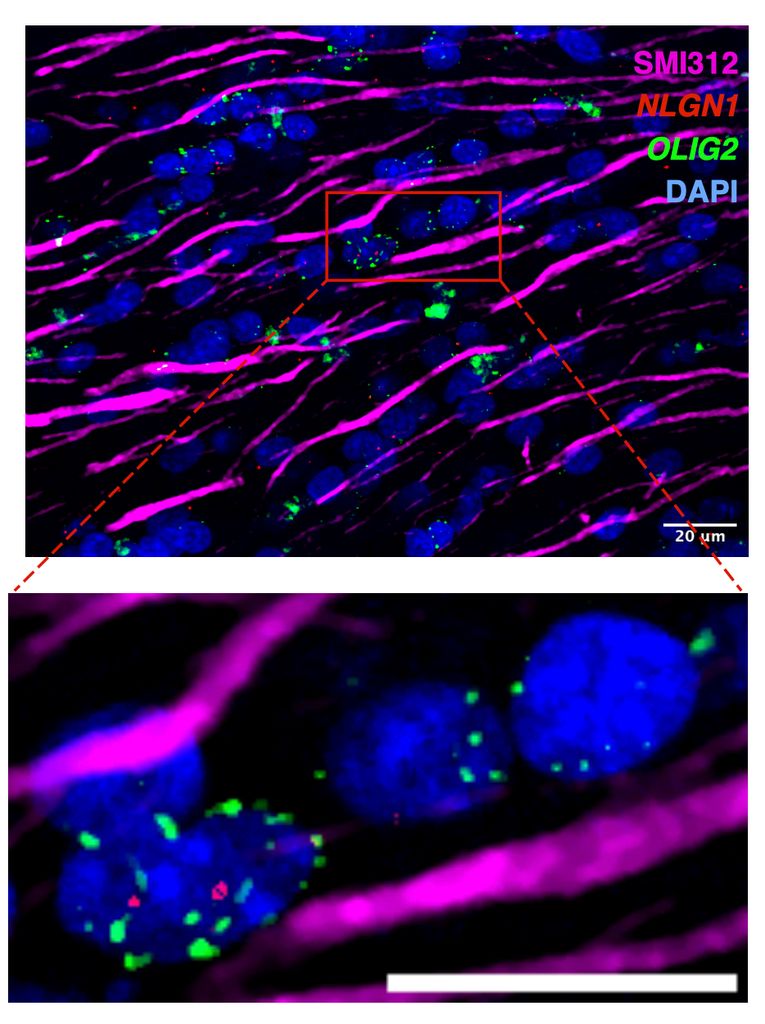

Axonal nerve fibers (magenta) surrounded by supporting brain cells, whose nuclei are stained blue. Green puncta show OLIG2 mRNA, which identifies oligodendrocytes the brain cells that form the protective myelin sheath around nerves. Red puncta show NLGN1, a molecule that helps these oligodendrocytes connect to nerve fibers. Normally, aging reduces NLGN1 levels, disrupting myelin formation. However, researchers found that long-term calorie restriction helps maintain NLGN1 expression, potentially preserving healthy nerve insulation and communication.

Axonal nerve fibers (magenta) surrounded by supporting brain cells, whose nuclei are stained blue. Green puncta show OLIG2 mRNA, which identifies oligodendrocytes the brain cells that form the protective myelin sheath around nerves. Red puncta show NLGN1, a molecule that helps these oligodendrocytes connect to nerve fibers. Normally, aging reduces NLGN1 levels, disrupting myelin formation. However, researchers found that long-term calorie restriction helps maintain NLGN1 expression, potentially preserving healthy nerve insulation and communication.

The researchers used a technique known as single nuclei RNA sequencing which allowed them to assess the molecular profile of individual brain cells. They compared the brain cells from subjects who ate a normal diet versus the calorie restricted diet, which allowed them to see how eating fewer calories influenced the expression of genes and activity of pathways linked to aging in brain cells.

The calorie restricted brain cells were metabolically healthier and more functional, exhibiting increased expression of myelin-related genes and enhanced activity in key metabolic pathways (glycolytic and fatty acid biosynthetic pathways) that are crucial for myelin production and maintenance.

Tara Moore, PhD

Tara Moore, PhDAccording to the researcher, these findings support that long-term dietary interventions can shape the trajectory of brain aging on a cellular level. “This is important because these cellular alterations could have implications that are relevant to cognition and learning. In other words, dietary habits may influence brain health and eating fewer calories may slow some aspects of brain aging when implemented long term,” adds co-author Tara L. Moore, PhD, professor of anatomy & neurobiology.

These findings appear online in the journal Aging Cell.