Medicine is Global: Our alumni, faculty, and students are engaged all over the world.

Cover Story

Our alumni, faculty, and students are engaged all over the world

Christopher Strader, MD’15, MPH’09, first traveled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the summer before his second year of medical school to work on a BU-sponsored project. Initially, what struck him was seeing residential front doors tied shut with string.

He asked the physician with whom he was traveling about it and was told that break-ins were epidemic in a war between Congolese soldiers and rebel insurgents, with soldiers using rifle butts to knock on the door handles.

“At some point, you just stop putting the door handles back on,” says Strader, now a cardiothoracic surgery fellow at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

Healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa presents challenges, including political and social unrest, lack of medical personnel and the infrastructure to train them, limited surgical care, and medicine shortages. But Strader found something on his first trip to the Congo that has inspired him to keep working in global healthcare.

“I started doing it because I felt this is the human contract, that we should help each other,” says Strader, who was named a Harvard Medical School Paul Farmer Global Surgery Fellow in 2018. The fellowship was created to train leaders to tackle inequities in surgical care, education, and research related to global health.

Strader keeps returning to work in low-income countries, as doing so renews his faith in medicine as a force for good. The Congolese physicians he works with aren’t mired in the complexities of electronic medical records or upset because their on-call schedule has changed.

“These men and women show up each day to do what is difficult. They do it for the love of the art of medicine,” Strader says. “Being with people who do it because they love it reminds me why I’m doing it—because I love it.”

From medical students, to midcareer professionals, to retirees with hundreds of medical missions overseas, the desire to do good—to help improve global healthcare by creating programs and collaborating with partners in-country to improve access, availability, and affordability—runs strong among Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine alumni.

“You go into medicine because you like people; because you want to take care of people,” says Andrew Wexler, MD’80, a retired plastic surgeon. “Working as a volunteer, in low-resource countries, distills the practice of medicine to its essential core. You have skills, these people need your help, and you receive their thanks for doing so. It’s a wonderful feeling and it’s why I went into medicine.”

Wexler, who splits his time between homes in Los Angeles and Cape Cod, has been doing surgical missions for 30 years, traveling to 27 countries where he often cares for children.

“The love of a parent for their child is universal and a palpable energy. When you intervene and help their child, some of that energy comes back to you in the love and care the parents have for you,” he says. “That feeling is as addicting as a drug, and it makes you want to go back, time and time again, to do the work.”

Wexler does a lot of cleft palate surgery. Sadly, children with facial deformities and their parents are often stigmatized, living isolated from their communities.

“You go into medicine because you like people; because you want to take care of people.”

“When you fix a child, you fix a family, and you add to a community,” he says. “It’s a bit like throwing stones in the water and watching the circles radiate outward. If we throw enough stones, we can make waves, and those waves can really make a difference.” Access to affordable healthcare is a global problem. According to the World Health Organization/World Bank “Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2023 Global Monitoring Report,” almost 58% of the world’s population—4.5 billion people—are not covered by essential health services, and 1.3 billion people are pushed into poverty each year by catastrophic out-of-pocket healthcare spending, primarily in lower- and middle-income countries.

Surgery is the most expensive of the global medical missions. But 90% of the world’s poor lack access to safe and affordable surgical care even though the Global Surgery Foundation has determined that each year, total surgically avertable deaths alone are approximately six times greater than total deaths from HIV, malaria, and TB combined.

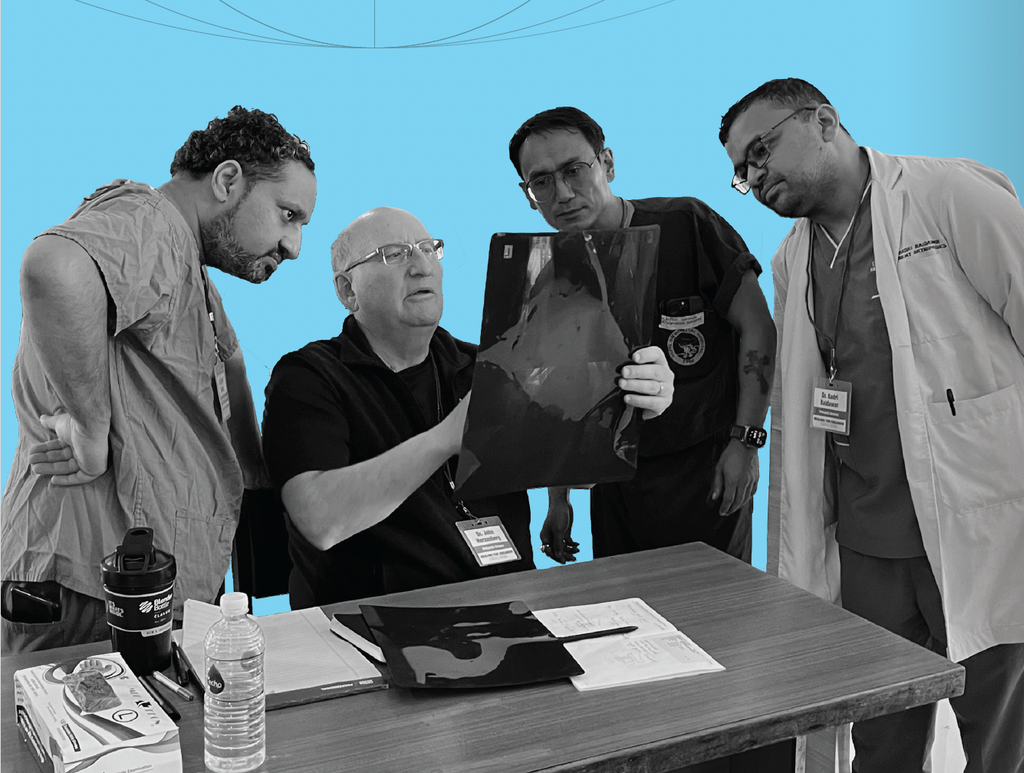

“A lot of injuries don’t get treated,” says John Herzenberg, MD’79, (page 23, seated) a retired orthopedic surgeon specializing in pediatric orthopedics and a surgical technique known as limb lengthening, which uses the bone’s capacity to grow in small increments over time to help heal crippling deformities, some of which are directly attributable to the lack of surgical care.

“It is restoring hope, altering a person’s life,” he says. “In many of the cases we treat, if we weren’t there doing it, it wouldn’t be done.”

In countries with limited or no access to surgical care, a femur break, for instance, can be both physically and financially crippling.

“If they don’t have the ability to operate on you, they just put you in traction or a cast and you’ll be lying in bed for three months, not going to work, not making money for your family, and incurring costs for being in the hospital,” says Herzenberg, who has been volunteering and organizing overseas surgical missions for 26 years.

“It is restoring hope, altering a person’s life. In many of the cases we treat, if we weren’t doing it, it wouldn’t be done.”

He stresses that the key to successful surgery is follow-up, which was problematic for short-term medical missions until recent technological developments.

“Even in the most remote portions of Africa, people have cell phones,” he says. “I can maintain direct contact with the doctor and with the patient, and it’s almost like I’m there.”

Technology also has improved efforts to train local doctors. Herzenberg was recently in Nepal, working with a team of four local orthopedic physicians.

“We taught them a lot of new procedures. They loved operating with us,” he says. Post-departure, the US surgeons formed a WhatsApp group with the Nepalese physicians, who would send them x-rays of patients they had worked on together, asking questions about follow-up care and patient progress.

The drive to help individual patients often leads to the desire to tackle systemic problems like access, availability, and affordability. According to Jamel Patterson, MD’88, helping people is part of her Christian faith. Now retired, Patterson was an emergency room physician in New York City’s public hospitals for most of her career. Originally from Jamaica, she participated in medical missions to her native country, but it was her first mission to Uganda that opened her eyes to the enormity of the global need for healthcare access.

“A lot of people come out when we go to Jamaica, but it’s not like that [in Uganda],” Patterson says. In Uganda, thousands would show up.

“They waited patiently. Nobody pushed; nobody fussed. They sat quietly in the sun, waiting to be seen,” she recalls. “When we were finished, during the debriefing, I cried.”

The disparity of her work in a fully equipped Harlem hospital and what she’d experienced in Uganda weighed on her.

Conversations with other doctors from the medical mission produced an initiative to buy mosquito netting, a malaria preventative, and distribute it in the regions where they’d worked. That led them to form the Ageno Foundation. After consulting with locals, the foundation used donor money to drill deep wells and install pumps that ultimately provide clean water to 500,000 people in Africa and India. Their programs have expanded to include education, economic empowerment, healthcare, and nutrition.

“Healthcare should be universal, for everyone. It shouldn’t be a privilege,” Patterson says.

Early in his career, the goal was to help as many patients as possible, says plastic surgeon Larry Nichter, MD’78 (shown above with the 14th Dali Lama). Cleft palate surgery is the most frequently performed procedure for short term medical missions. In part, that’s due to the condition’s prevalence in low and middle-income countries, where factors like poor nutrition, smoking, and genetics make it more likely to occur.

“You see these kids with these wide cleft lips, and they can’t speak, they can’t really eat well, and the whole village is affected because the mom can’t work; she must stay with the child,” he says. “We operated as fast as we could and as furiously as we could, and we’d do 14, 16 hours of surgery…and we trained no one.”

But on one trip, Nichter decided he’d stay a little longer. He spoke to local surgeons, and they told him the foreign surgical teams undermined the confidence of the local population in the skills of local physicians and surgeons to the point where patients were delaying necessary surgeries until the foreign team returned.

“The [local surgeons] were bright, they had great surgical skills, and they would have loved to work with us, but we didn’t work with them because it was faster to do it ourselves,” Nichter says. Critics of the short-term surgical missions charged that the missions had exhausted the local hospitals’ stock of drugs and surgical and recovery supplies, and also saddled them with high personnel costs due to the increased sta.ng necessary to support their busy operating schedule.

Initially, Nichter couldn’t get nonprofits interested in funding trips that would spend part of their time training local providers or expend money purchasing extra supplies to shore up local healthcare capacity.

“The donor always wanted to know ‘How many cases did you do?’” he says. “It was always the same question, but to me the metric of success was how many cases were done after you left.”

In 1999, Nichter founded Plasticos Foundation (now known as Mission Plasticos), an all-volunteer organization with the goal of leaving behind the best, most sustainable footprint by working closely with the local healthcare network and providers.

They purchased supplies in-country to put money into the local economy and trained local surgeons and other healthcare professionals onsite and in the US through fellowships.

“The [surgical missions] industry is basically coming around to the model we have at Mission Plasticos,” says Nichter, who recently received the 2024 Noordho. Humanitarian Award from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan.

Sometimes, the mission is intensely personal, immediate, and fraught with risk.

A month after a devastating earthquake struck Armenia on December 7, 1988—leveling three major cities and the surrounding countryside, killing between 25,000 and 50,000 people, and injuring up to 130,000— Carolann Najarian, MD’80, found herself in a very bumpy descent into the country on a cargo plane full of donated supplies.

“We weren’t thinking about our safety,” Najarian recalls. “You don’t think about it because what you’re thinking about is that you have to get help to these people.”

Hospitals and apartment buildings had collapsed. People were living in temporary housing, often metal containers used to transport goods on ships, in winter conditions without heat, water, or insulation. Najarian, whose parents survived the Armenian genocide and emigrated to the US, founded the Armenian Health Alliance to coordinate and deliver medical supplies and expertise to the region. She made more than 60 trips to Armenia and established a primary care clinic and a center for pregnant women.

Although she was there to deliver aid, Najarian saw patients, too. She hadn’t delivered babies since her third-year medical school rotation, but she worked in a maternity ward. The earthquake happened in the middle of a war with Azerbaijan, and Najarian made frequent trips into the war zone on Soviet helicopters that were easy targets, and triaged patients in a front-line surgical unit set up in an abandoned house.

“You are using every single bit of medical training you ever had,” she says. “I’m not a religious person but I do feel there’s some kind of destiny involved. I got my training; I became a doctor, and I was able to answer the call.”

When she returned to Liberia in October 2005, Mardia Stone, MD’78, MPH, found her native country was greatly changed. A civil war had killed between 150,000 and 250,000 people, displaced half the population of 3.5 million, and reduced the country to rubble.

“The Liberia I knew as a child when I was growing up doesn’t exist anymore,” says Stone. “Monrovia was a developing metropolis, but after the war it was like a shantytown.”

“I felt a sense of duty, a sense of responsibility.”

Stone was a member of the newly elected, first female president Ellen Johnson Sirfeaf’s transition team, chairing the team focused on health and social welfare. Her first task was an in-depth analysis of the country’s healthcare system.

Despite the chaos and profound lack of infrastructure, Stone found it rewarding and exciting to deal with a broad range of people, politicians, international aid organizations, activists, and committed Liberians who were working to rebuild the system.

“I had only worked in hospitals or in clinics previously in Monrovia. Chairing the health sector transition team broadened my horizon, and I began to actually enjoy the work and my service to the nation,” she says.

Stone worked in Liberia from 2006 to 2013 and was called back there in 2014 by Tolbert Nyenswah, LLB, MPH, DrPH, who was leading the country’s response to Ebola. At the time, not much was known about the disease except that it was nearly always fatal. Fear and distrust of government and outsiders prevailed. A law made it a crime to hide Ebola patients, physicians and healthcare workers were dying, and government officials and foreigners were fleeing the country.

“People would literally die in the street,” she says.

Stone traveled on fact-finding missions in convoys guarded by soldiers, driving on rutted and flooded dirt roads to remote villages whose citizens distrusted their government and healthcare workers and feared strangers who might spread the disease. Each time Stone returned from a trip, she’d bag the clothes she’d worn that day and dispose of them. Then she would wipe down her shoes with bleach.

“I felt I had a sense of duty, a sense of responsibility,” she says. “I had an affinity for this place, the land of my birth. I felt if I had not gone, I would have been remiss. So, once I decided to go, I was fearless.”

To Joshua Feder, MD’86, living with and managing fear is integral for his patients. For half of his time on California based psychiatrist, works pro bono with conflict areas dealing with the psychological impacts of war on children.

Feder is the programmatic lead for the International Networking Group on Peace Building with Young Children and the cochair of the Disaster & Trauma Issues Committee of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

“Our big concern is that children are going to be traumatized and radicalized by these wars, whatever side they are on,” he says.

A US Navy veteran who attended BU’s medical school on a Navy scholarship, Feder has traveled to the Middle East, Northern Ireland, and the Balkans on missions supporting those communities and is an adjunct professor at An Najah National University in Nablus on the West Bank.

“I am working with Palestinian, Israeli, and Lebanese communities in the current war, trying to help people to remain responsive to the children and protect them as much as possible from the violence,” he says, adding that psychiatry is poorly funded compared to other international medical missions and that unlike a cleft palate or a broken limb, the damage is hidden and harder to repair. “It’s gratifying work, and our data gives us real hope that children impacted by conflict can go on to build more functional,

peaceful societies.”