Five Stories from the Front Lines

Since late February, once it became clear that Boston would not escape the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the city’s hospitals have been preparing for the greatest patient surge in their history. Planned surgeries were canceled, workflows redesigned, doctors reassigned, and special clinics erected.

At Boston Medical Center (BMC), the city’s safety net hospital serving the most underserved, vulnerable patient populations, and home to one of the country’s busiest emergency departments, doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and other staff are running both a sprint and a marathon. It is an all-hands-on-deck moment to help rescue a tidal wave of patients from a novel disease they know little about—and whose transmission can put their lives and their loved ones’ lives at risk.

In barely two months, in addition to admitting more than 180 patients with confirmed or possible cases of coronavirus, BMC has more than 100 employees who have tested positive for the disease. And the presumption is that it’s going to get worse before it gets better.

BU Today talked with five BMC physicians—who also hold faculty positions at the Boston University School of Medicine—about working on the front lines, their efforts, fears, and frustrations, as well as their reasons for hope.

From chaos, progress

Evan Berg

The emergency department at Boston Medical Center is a place where doctors and nurses are ordinarily unfazed by patient surges and where the staff take pride in their ability to handle any injury or infection—or even mass casualty event—the city can throw at them. But COVID-19, says Evan Berg, an attending emergency room physician for 16 years and vice chair of clinical operations for the emergency department, is something entirely different. Read more

The emergency department at Boston Medical Center is a place where doctors and nurses are ordinarily unfazed by patient surges and where the staff take pride in their ability to handle any injury or infection—or even mass casualty event—the city can throw at them. But COVID-19, says Evan Berg, an attending emergency room physician for 16 years and vice chair of clinical operations for the emergency department, is something entirely different.

“This particular infection poses a lot of additional challenges, as we have had to rapidly learn about how best to protect ourselves and one another, patterns of transmission, and best practices for treatment,” says Berg. “There is a lot of uncertainty about the disease process. Even though the majority of people do exceedingly well, there is a minority of people who don’t do well. Trying to understand why that is—and find some clinical markers and understand the risk factors—has been a learning process for all. That has been a challenge that all in the healthcare system have readily and capably responded to over the last six weeks.”

The good news, says Berg, is that approximately 80 percent of people with COVID-19 don’t need to go to the hospital. The challenge, however, is understanding how to efficiently evaluate and manage the patients who do need hospital care. “Our understanding around the transmission, the continuum of the disease, the duration of symptoms, best practices around treatment, and the outcomes for those needing hospitalization continue to evolve as we learn more and gain experience,” he says.

Curiously, the number of patients coming to the emergency department has actually dropped from roughly 400 patients a day to about 250, he says, and he thinks that’s because people are heeding advice and staying home. But fewer patients doesn’t mean less stress, he says. For one thing, a greater percentage of those who show up may have COVID-19.

“It feels like you’re walking through molasses,” Berg says. “You have to be so careful. The doctors and nurses have to be careful about how they don the PPE [personal protective equipment], and how they take it off. They have to be careful about which patients go into which room and which patients should go into a hallway.”

Emergency physicians are actively learning about the red flags and understanding which patients are safe to send home, he says. “We know much more of these things with diabetes and congestive heart failure. We don’t yet with COVID-19. So there is uncertainty, and this can lead to fatigue.”

Despite the anxiety, and because of it, Berg says, emergency room staff are adapting.

“It’s like learning to drive. As we [treat patients] again and again, it can be draining, but it creates a kind of muscle memory as we try to be efficient and safe and consistent. It’s amazing to see how far advanced we are today from where we were a week ago. But it’s like we are building the ship as we are passing over the seas.”

Still, Berg sees “enormous steps forward” on several fronts. Clinicians have a better understanding of what kinds of PPE should be used in different areas of the hospital. After relying on tests whose results could take up to a week, they now have in-house testing that provides results in 8 to 24 hours. And the care for homeless patients with suspected COVID-19 who don’t need hospitalization has seen tremendous progress, thanks to work by many people.

“Just a couple of weeks ago we had to admit any homeless patient who had suspected COVID-19 to the hospital because shelters could not take them in and there were no other safe housing options,” Berg says. “Also, we were relying on tests whose results were taking up to seven days, and initially testing required Department of Public Health approval. Now we have in-house testing at Boston Medical Center and we can get results in 8 to 24 hours. Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program is taking patients who have pending tests and positive tests, but aren’t in need of hospitalization and who can be discharged and cared for at Barbara McInnis House and in tents being staffed with healthcare personnel.”

Berg’s department has added significant provider and nursing hours on the fly and changed hours based on needs. They worked with IT leadership to make critical updates to electronic medical records, so providers know which patients may have COVID-19 so they can make proper decisions on bed utilization. With help from BMC’s ambulatory clinics, they also set up an influenza-like illness (ILI) clinic in the Shapiro Building that treats many patients who might have ended up in the emergency department.

“The amount of collaboration is amazing,” Berg says. “We have such a better footing now than we did two weeks ago. We have better anchors on fundamental stuff like PPE, test turnaround, medical records, admissions, how we handle homeless patients. All of that is the silver lining.”

The pandemic has also prompted rapid innovation, he says. Before COVID-19, hospitals’ telehealth services were limited, but patients now get regular phone and video visits from clinicians. And the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has loosened practices to reimburse hospitals for services provided outside the hospital. “The way people are trying to figure things out on the fly and test them, analyze, and adjust is amazing,” Berg says. “Part of the reason we’re in this predicament with surge and capacity is because we didn’t innovate, because we didn’t have to. I’m curious to see what the system-wide, long-term outcomes are. I hope we can learn from this. I hope we can take lessons about efficiency and connectivity across departments and clinical siloes. I hope those lessons aren’t forgotten.”

Service and sacrifice

Kristen Goodell

At the end of a recent three-mile run with her teenage daughter and son, Kristen Goodell raised her hand for a congratulatory high five. Then she lowered it. That familiar gesture, she remembered, was no longer permitted. In the new normal, Goodell, associate dean for admissions and an assistant professor of family medicine at Boston University’s School of Medicine, cannot touch her children. And her children cannot touch her. Read more

At the end of a recent three-mile run with her teenage daughter and son, Kristen Goodell raised her hand for a congratulatory high five. Then she lowered it. That familiar gesture, she remembered, was no longer permitted. In the new normal, Goodell, an assistant dean for admissions and assistant professor of family medicine at BU’s School of Medicine, cannot touch her children. And her children cannot touch her.

That new normal introduced itself to Goodell on Saturday, March 14, three days after BU announced that it would move to remote learning in an effort to slow the spread of coronavirus. Goodell was hiking up Mount Wachusett with her family when she got a call from Tu-Mai Tran, medical director of Boston Medical Center’s family medicine clinic on Melnea Cass Boulevard. Tran asked if Goodell would be willing to test patients for coronavirus in a new pop-up influenza-like-illness (ILI) clinic. Goodell said yes.

“I knew my family was not going to be crazy about me doing this,” she says. “But I said, ‘OK. Here’s what we’re going to do. I’m going to work in this clinic, and I’m going to move into the guest room on the lower level, and I am not going to make food for anyone. I’ll come home, throw my clothes in the wash, take a shower, and try to keep away from everybody.’

A New Home for the New Normal. In this iPhone video, Kristen Goodell tours her temporary residence, which helps distance her from her family while at home. (Click image to view video)

A New Home for the New Normal. In this iPhone video, Kristen Goodell tours her temporary residence, which helps distance her from her family while at home. (Click image to view video)

In admissions, Goodell’s days were usually dedicated to reading MED applications and interviewing applicants. This time of year, in addition to speaking engagements and panel discussions, she also saw patients on Tuesday mornings and Thursday evenings, mainly at the family medicine clinic. The first hint that that might change, she says, arrived in early March.

“We were starting to keep our eye on the pandemic,” Goodell recalls. “There had been one case in Boston—a UMass student who had come from China. We knew about the situation in China and elsewhere. At the medical school, we started asking what this could mean for Boston and what we needed to be thinking about.”

Goodell had wondered how a family medicine doctor like herself could help, particularly at the time of year when her office workload was a little lighter than usual. Like most BMC doctors, she had considered the possibility that a surge of COVID-19 patients might call many to the front lines. But the gravity of the impending crisis didn’t hit home until she received a survey from the family medicine clinic, asking those not routinely involved with inpatient care to rate their ability to provide such care. “That was one of my greatest moments of coronavirus terror,” she says. “My first thought was, things must be really bad if they need doctors like me to take care of patients in the hospital. I haven’t done that since 2009.”

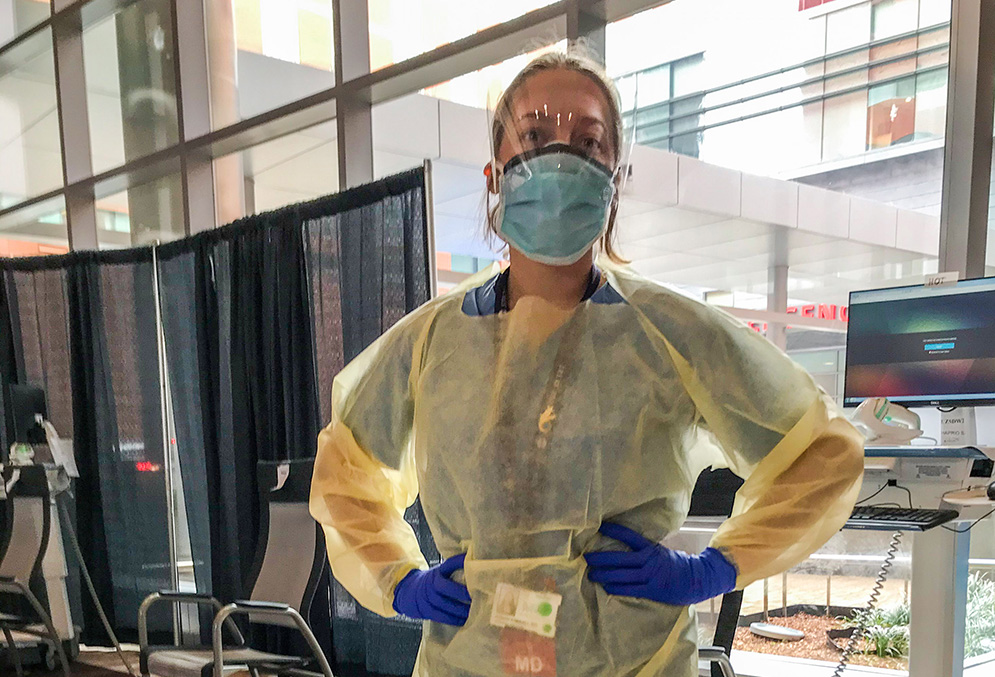

At the ILI clinic, Goodell was outfitted in complete personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes a cap, a yellow gown, and an N95 mask and face shield. Clinic doctors wear two sets of gloves, changing the outer pair from patient to patient. She told administrators that she was available to work any hours. “I was thinking morning or afternoon, maybe eight to five,” she says. “They said, ‘OK, it’s going to be eight to eight.’ I didn’t expect that. After the first day, I said, ‘You know, 12 hours is a really long time when you are wearing personal protective equipment that’s hard to put on and take off.’ You can’t just go to the bathroom or even take a drink of water. You have to take everything off and put everything back on.”

The clinic now offers doctors two shifts: from 8 am to 1 pm and from noon to 5 pm, with two doctors on each shift. Goodell—along with other doctors from family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics—works varying shifts each week. The clinic sees about 50 patients a day, and tests about 18, taking a nasopharyngeal swab that is sent to the lab.

Although doctors at the clinic query patients using a clear template with yes-no answers, Goodell says she can’t stop being a primary care doctor. “I start by asking them, ‘So, what’s going on with you?’” she says. “I find that about 50 percent of the people have symptoms and are actively worried that they have the coronavirus. The other half aren’t worried, but they ‘screened in’ when they came to the hospital or called their doctor for another reason. I try to figure out their risk for coronavirus, ask them to go over their symptoms, and then if testing is warranted, we do the test.”

The decision to test or not is complicated. “We don’t have enough tests for everyone who I think should be tested,” says Goodell. “Some days we are able to test more people because we have enough supplies. Some days we are told that we are only testing people who are at a high risk of spreading the virus to others—for instance if they live in a homeless shelter or are sleeping on the street or are healthcare workers.”

Goodell comforts patients who aren’t being tested, assuring them it doesn’t mean they aren’t being appropriately treated. “The difficult fact is, even if it is coronavirus, if you don’t need to be in the hospital, the correct treatment is to rest, take Tylenol, and monitor your breathing,” she says. “If it’s a virus, it has to run its course. People should stay home and take good care of themselves.”

Despite the frustrations stemming from equipment shortages, Goodell says the patient contact at the clinic can be immensely rewarding. “It’s why I became a doctor,” she says. “I thought the thing that’s most important to people is being healthy and if I could be a doctor I could help people get healthy and stay healthy. It’s gratifying. Even though I can’t test all the people I want to test, I can use every communication skill I ever learned. I can dig deep into my well of patience and concern and have moments of connection with people who are really scared. I can make them feel a little bit more comfortable, a little less scared, and a little bit better prepared with some actions they can take.”

She says she is not scared. She is careful to protect herself at the clinic and her family at home. When she comes home at night, she enters through the lower level, where a one-bedroom, one-bathroom guest suite will be her primary living space for at least the next three months. From the upstairs, she can hear her family preparing dinner—another family routine that she no longer shares. She still does eat dinner with her family, but sits alone at the far end of the table.

In the morning, Goodell makes her own coffee and toast and gets out of the house by 7 am. The minute the door closes behind her, she says, her husband wipes down the kitchen with disinfectant.

None of the new routine comes naturally, and some of the seemingly trivial changes have been surprisingly difficult. “We have a decent-sized playroom,” Goodell says. “That’s where our television is, and we can still watch movies together if we sit far apart. Normally, when we watch movies, we like to cuddle. These days, I can tell that my kids keep wanting to give me a hug. We can’t do that.”

Anxiety, determination, and hope

James Hudspeth

On Friday, April 3, James Hudspeth admitted three patients to Boston Medical Center. “I would not have told you at the end of that shift I was worried about any of those patients going to the ICU,” says Hudspeth, who oversees the hospital’s COVID-19 response inpatient floor. “But at the end of 24 hours, two of those patients were in the ICU. As an experienced doctor, that is very disconcerting. I’ve been doing this for 14 years, and I have a very good sense of a patient with pneumonia, who looks good and who looks bad, and what kind of patient I need to worry about. COVID-19 upends all that.” Read more

On Friday, April 3, James Hudspeth admitted three patients to Boston Medical Center. “I would not have told you at the end of that shift I was worried about any of those patients going to the ICU,” says Hudspeth, who oversees the hospital’s COVID-19 response inpatient floor. “But at the end of 24 hours, two of those patients were in the ICU. As an experienced doctor, that is very disconcerting. I’ve been doing this for 14 years, and I have a very good sense of a patient with pneumonia, who looks good and who looks bad, and what kind of patient I need to worry about. COVID-19 upends all that.”

Hudspeth’s general medical admissions floor houses COVID-19 patients who are too sick to stay home, but not sick enough to require intensive care, and patients undergoing testing for COVID-19. On April 5 there were 176 such patients at BMC. Most will get better. Some will get worse.

“One patient came in with a positive COVID-19 test and about six days of symptoms,” he says. “He was a slightly heavier gentleman with hypertension—all of which we increasingly appreciate are risk factors for worse outcomes. He came in just on the edge of where we would put someone on oxygen, and I would typically expect someone like that to get better or worse over the course of several days. He was in the ICU the next morning, and on a ventilator the next evening. That speaks to how this is a new disease that acts in different ways.”

One difference is the speed at which the disease can move, both through patients and through the population. Hudspeth is reluctant to estimate the number infected, largely because things have been changing very fast. “In the beginning of March, when we had 20 patients who were being ruled out for COVID-19, one or two actually had the disease,” he says. “Now we are seeing an epidemiological shift. At this point, when a patient comes in, our thinking is that this is COVID-19 and that’s what we’re going to work up first.”

Nurses and doctors on the floor do what they can to support the patients. They check the lungs, kidneys, and blood pressure, and carefully monitor breathing. And they try new things.

Every day, Hudspeth says, the hospital’s infectious disease doctors revamp treatment algorithms used to help make medical decisions and devise new treatment approaches based on literature being produced day by day, week by week, across the world. Over the course of a month, they considered using HIV medications, such as lopinavir and ritonavir. But a small study indicated those may not be helpful. Other small studies have supported the use of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine.

“Our infectious disease doctors have a very nuanced perspective,” Hudspeth says. “They don’t think that these are miracle drugs, and they still don’t know if they work, but if there is enough of a suggestion that they may have a benefit, and don’t cause a problem, then it’s worth using them for the moment, but being very thoughtful about what the data show us as new information comes out.”

At BMC, many patients arrive with health problems like diabetes, hypertension, or heart disease—medical conditions that could be exacerbated by either COVID-19 or by its treatments. Almost every COVID-19 patient in the hospital is extremely stressed, and many live each day with high levels of psychosocial stress.

“We are used to dealing with an underserved population at BMC and dealing with patients who have a great deal of psychosocial stress across the board,” says Hudspeth. “We try to reassure patients who are afraid because of the disease, and we try to address psychosocial issues concerning things like homelessness and substance abuse. COVID-19 adds another level of complexity because patients can’t go back to a shelter, can’t go back to some treatment programs, and some can’t go back to crowded housing they share with vulnerable family members.”

At the same time, BMC’s healthcare providers are dealing with their own unprecedented levels of stress—much of which, Hudspeth says, depends on people’s home situations. “For me it’s not so bad,” he says. “I don’t have children and I don’t live with my parents. My wife is a primary care physician who is working in an ILI clinic at BMC. We had a forthright discussion at the beginning of this. We decided that we were both comfortable working with these patients. We accepted that there was some level of risk, and we accepted that if we become infected the probability of either of us having a bad outcome was low. I think for colleagues that have children or older parents at home or have personal medical issues placing them at higher risk, this is a very challenging decision. I’m thankful that at BMC we have enough providers that we can keep people who are at higher risk away from the front lines and use them in other roles to support our efforts.”

For Hudspeth, however, COVID-19 has curtailed a reliable routine exercise in stress relief. “Ordinarily, when I have a tough day, I just go sit with one of my patients and talk to them for a while,” he says. “That is a very restorative thing, to be reminded that this is a human who I am helping to try to feel better with my work. With this situation, I have to be gowned up, I have to be wearing a mask, and that really detracts from the human connection. It adds a lot more stress to the situation.”

Hudspeth says he has seen “tremendous progress” in the four weeks since the inevitability of COVID-19 settled on doctors at BMC. “I feel like the people in infectious disease grasped the enormity of what was going to happen,” he says. “Then everyone agreed that this is real and this is happening, and we started to see patients, and since then there has been a very well-organized structure to address this. Operationally, we have reorganized the hospital in very fundamental and important ways.”

Collaboration has been critically important in that regard, Hudspeth says. “We know the strategy people, and the head of physical therapy, and head of the lab, and this situation is requiring all of us to come up with new operations and new workflows on a daily basis, and to communicate that to our front lines and reinforce them in real time,” he says. “It’s a real testament to the people we have here and the connections that people have built up over the years that we’ve been able to do this with the degree of success and precision that we have seen. Two months ago, to think that we would be doing this would have been risible.”

“We’ve built structures,” he adds. “Now the question is whether what we built is going to be resilient enough and strong enough to make it through the next several weeks.”

Stemming collateral damage

Sarah Kimball

For Sarah Kimball, a primary care doctor and codirector of Boston Medical Center’s Immigrant & Refugee Health Center (IRHC), life has changed with two sudden shifts. First, three weeks ago, the IRHC halted in-person visits and moved all communications to telephones. The risk of infection from COVID-19 had made person-to-person contact far too risky. One week later, Kimball accepted an invitation to codirect BMC’s newly launched influenza-like illness (ILI) clinic, which operates in the Shapiro Building. Read more

For Sarah Kimball, a primary care doctor and codirector of Boston Medical Center’s Immigrant & Refugee Health Center (IRHC), life has changed with two sudden shifts. First, three weeks ago, the IRHC halted in-person visits and moved all communications to telephones. The risk of infection from COVID-19 had made person-to-person contact far too risky. One week later, Kimball accepted an invitation to codirect BMC’s newly launched influenza-like illness (ILI) clinic, which operates in the Shapiro Building.

There, Kimball wears full personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes a face shield, an N95 mask, a gown, and double-layered gloves. She moves from patient to patient, each seated at least six feet apart, asking about symptoms and their occupations. “We want to know how sick they are, what symptoms they have experienced, where they work, and if they are homeless,” Kimball says. “We do a symptom screener and then we do a risk screener.”

Patients are sent in one of two directions, based on Massachusetts Department of Public Health guidelines. They either go home or to the emergency room. That protocol is necessary, says Kimball, but it can result in some painful partings. For instance, a married couple visiting from out of town came in with potential COVID-19 infections, but while the sicker husband was triaged to the emergency room, the wife was only symptomatic.

“Our current rules state that you can’t send people to the emergency room if they are only symptomatic,” Kimball says. “So, we had to tell the wife that she couldn’t go with her husband. This woman doesn’t even live here. We had to figure out where she could go. I can’t imagine being sick enough to go to the emergency room right now, when people are very afraid, and having to do it removed from a family member. It’s so hard on people. It adds to the fear factor.”

In her first week on the job, March 30 to April 3, the busiest day saw 100 patients. Kimball expects the number to climb quickly in the next few days. In addition to directing patients to the proper level of care, she tries to ease the stress on a patient population that is very scared, often about their income as well as their health. One patient, for instance, came in with a sore throat and mild fever, but was most anxious about her ability to return to work.

“If she couldn’t work, she couldn’t pay the rent, and she was really worried about food. So, even more than her health risk, she was worried about her family making it through the week economically,” Kimball says. “That speaks to the level of difficulty that many patients are living with. If you are living on the margin, COVID-19 can push you over. Working at BMC, a safety net hospital, reminds us what a privilege it is to be able to quarantine, to have the space in your home, and the financial security to not go to work.”

Kimball does her best to reassure patients. She provides them with “work letters,” stating when it is safe for them to return to work, based on US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. Those guidelines require that at least seven days have elapsed since the start of symptoms, and that there have been no symptoms for three days, including the resolution of fever without medication.

Kimball’s concerns about the collateral damage of COVID-19 include the many people who depend on BMC’s Preventive Food Pantry. “If those people are sick and can’t come in, how do we get food to them?” she asks. “I know that people at BMC have been working hard to develop a COVID-19 fund that would help send food and groceries. Our development team has put a lot of energy into this.”

She also worries about the immigrant and refugee community that has been the focus of her work at the IRHC for six years, and is now served only by telephone. “A lot of these people have limited proficiency in English,” she says. “Many of them have gig jobs like driving for Uber, or are frontline health workers like health aides. We have to think about how to adapt the model of care to a population that has so much more vulnerability.”

For people who live with immigration-related fear, Kimball says, COVID-19 has really ratcheted things up. “Patients tell me they’re worried about deportation, and we are seeing many immigrants avoid healthcare services because of the Public Charge Rule, which can complicate immigration for people who accept some public benefits, even though COVID-19 testing and treatment is not considered under the rule,” she says. “So right now we are doing a lot of damage mitigation so they know it’s safe to come in for testing and treatment. That’s really important: if people don’t know it’s safe to go to the hospital, they put themselves and people around them at risk.”

Greater distance, stronger bonds

Michael Ieong

Michael Ieong, medical director for the Boston Medical Center’s intensive care units and assistant professor of pulmonary, allergy, sleep, and critical care medicine at Boston University’s School of Medicine, is accustomed to 12-hour days. But before the ICU filled with COVID-19 patients, his 12-hour days were spent coordinating disciplines and workflows, and as he puts it, “making sure everything works well.” He did rounds, did some teaching, and like other ICU doctors, responded to situations with the confidence that he was applying evidence-based best practices. Read more

Michael Ieong, medical director for the Boston Medical Center’s intensive care units and assistant professor of pulmonary, allergy, sleep, and critical care medicine at Boston University’s School of Medicine, is accustomed to 12-hour days. But before the ICU filled with COVID-19 patients, his 12-hour days were spent coordinating disciplines and workflows, and as he puts it, “making sure everything works well.” He did rounds, did some teaching, and like other ICU doctors, responded to situations with the confidence that he was applying evidence-based best practices.

“What has changed,” he says, “is we are now dealing with something where it’s not entirely clear what the best practice is. We are in uncharted waters, and it’s very hard to apply our regular clinical acumen to something we’ve never seen before.”

Ieong says COVID-19 presents doctors with two disturbing medical problems. One is the rapidity of the severe and often-fatal lung injury that afflicts some patients. The second is the length of time during which patients may recover. In most lung-injury cases, doctors can often tell within days if the patient is likely to recover. With COVID-19, the trajectory is much less clear, and it can take weeks to recover, tying up ventilators that are in very short supply.

“Another aspect of this that’s very different is the sense of personal threat to us and our colleagues and families,” says Ieong. “It’s something that every single nurse, provider, and student trainee is carrying around all the time. How you manage that is a challenge. It colors everything you do. We are being very conscious of everything we touch. We develop protocols and recommendations on what people should do—how they should get dressed in the morning, how they should disrobe in the evening when they come home, things they should think about at home.”

In his home, says Ieong, he no longer kisses his six-year-old daughter and no longer sleeps in the same room as his partner. And on those now painfully infrequent occasions when he visits his 93-year-old mother, who lives just across the street, he insists that both of them wear masks and stay six feet apart.

At BMC, much of the customary camaraderie has been put on hold. “The normal practice is that we will do rounds together,” Ieong says. “It’s always been very much a team effort. Now we try to stay away from each other. It’s very difficult to function as a team when you practice social distancing, and it’s impractical. Even things like using a computer that someone else has used has changed. The whole infrastructure of the hospital is designed to pull people together so they can collaborate. Now you are literally fighting to hold on to the collegiality, because that’s what keeps you going.”

However, he adds, “the overwhelming universal sense of one common opponent” in COVID-19 has helped maintain—and even intensify—the team’s single-minded goal of slowing and stopping the novel virus.

And all of this is happening far too fast. The ICU saw its first COVID-19 patient in mid-March. Within one week, there were four. Now an entire floor of the unit is filled, completely displacing its regular patients, who have been moved to the surgical space. All elective surgeries have been canceled. Surgical, cardiology, and neurointensivists are helping out with COVID-19 patients. All treatments are supportive, says Ieong. None are curative. “It’s mainly an effort to mitigate the patient’s severely impaired capacity to extract oxygen,” he says.

Ieong says BMC is ensuring that all patients are treated equally and that no group of people are shouldering the burden over others. The patient surge has not yet required doctors to make decisions about allocating potentially scarce resources like ventilators, but Ieong, who cochairs the hospital’s ethics committee, expects they might get there soon.

“The established ICU capacity in all hospitals in Boston is almost entirely tapped, and we are having to surge beyond it by creating new ICU beds,” says Ieong. “All of the ICU ventilators are being tapped, and we are starting to use operating room anesthesia ventilators. There are more patients getting placed on ventilators than are being liberated. In the end, the number of intubated patients just keeps increasing, accumulating in a way that you can’t get your head around. I suspect that sometime next week, we are going to be in dire circumstances.”

Under these circumstances, Ieong emphasizes that BMC will still “strive for transparency—being clear about what we are doing, so that we have the trust of our patients and our leaders, and everyone knows what we are doing, even if it’s less than optimal. The important thing is that everyone is certain that they are doing the best they can with what they have.”

This BU Today story was written by Art Jahnke.

View all posts