Day-long Seminar Celebrates the Life, Work and Legacy of Pioneering Black Psychiatrist Solomon Carter Fuller, MD

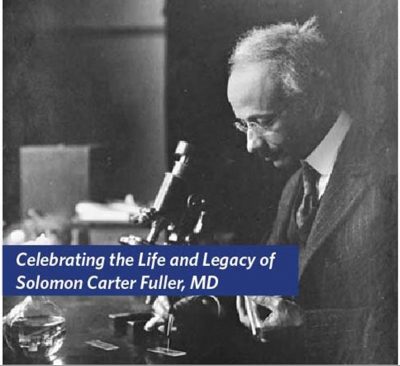

In one of the iconic photographs that accompanies discussions of the life and work of world-renowned neurologist, pathologist and educator Solomon Carter Fuller, MD, he is looking down at a glass slide, his microscope close at hand, focused on his task. The first Black psychiatrist in the United States, Fuller graduated from Boston University School of Medicine nearly 125 years ago in 1897.

In one of the iconic photographs that accompanies discussions of the life and work of world-renowned neurologist, pathologist and educator Solomon Carter Fuller, MD, he is looking down at a glass slide, his microscope close at hand, focused on his task. The first Black psychiatrist in the United States, Fuller graduated from Boston University School of Medicine nearly 125 years ago in 1897.

The grandson of slaves, he overcame obstacles of race with unwavering purposefulness throughout a 45-year career as a trailblazing scientist, academician and consultant. Recognized by his peers for the rigorous scientific approach he brought to psychiatry, Fuller himself believed he could have achieved more and risen higher if not for the color of his skin.

“Today, we celebrate Dr. Fuller’s achievements at a time when African American physicians faced even more barriers than today,” said BUMC Provost and BUSM Dean Karen Antman, MD, in her remarks opening the day-long seminar held Feb. 17, commemorating his life, his contributions to psychiatry and his legacy.

In highlighting his career, Antman noted that Fuller was chosen by Dr. Alois Alzheimer of the Royal Psychiatric Hospital in Munich as one of five foreign research assistants, and the only American scientist, to help him study the brains of dementia patients that led to the discovery of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Ahead of his time

“He was a visionary. He was completely ahead of his time,” said Chantale Branson, MD, assistant professor of neurology and course director at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta and an adjunct professor at BUSM.

This research uncovered abnormalities in brain tissue – twisted protein threads known as neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques, dense clumps of protein located between nerve cells. In 1912, Fuller published the first comprehensive review of the research that established it as a disease, not senility or insanity. Fuller’s research diverged from Alzheimer’s in highlighting the role of plaques over the neurofibrillary tangles. He also showed it was a disease of the young and old, and distinct from the dementia caused by arteriosclerosis, the hardening of veins with age.

“He was a visionary. He was completely ahead of his time,” said Chantale Branson, MD, assistant professor of neurology and course director at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta and an adjunct professor at BUSM.

Branson spoke on the historical life and times of Fuller that established his intellect and his drive to succeed and overcome obstacles.

Fuller’s paternal grandparents were former slaves who purchased their freedom and moved to Liberia. Fuller was born in 1872 in Monrovia, Liberia, and ventured to the U.S. as a teenager seeking an education. By 1897 he had graduated from BUSM, and within two years he’d advanced from an internship at Westborough Insane Hospital (whose name was changed to Westborough State Hospital in 1907 and closed in 2010) to Head Pathologist. In that same time span, he was named director of the Clinical Society of Massachusetts and an instructor of pathology at BUSM.

In 1909 he joined Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and 172 of the world’s leading psychologists, physicians and educators invited to an international conference at Clark University in Worcester. In a photo from the conference, he is one of 39 pictured posing with Freud and Jung.

But Fuller never rose above associate professor in BUSM’s neurology department, despite serving as the chair from 1928 to 1933, although he was never given that official title. He resigned in 1933 after a white assistant professor with less experience was promoted to professor and department chair. He continued in psychiatric practice in Framingham until his death in 1953.

Upon his retirement, BUSM appointed Fuller professor emeritus of neurology.

Persistent challenges

“He had an amazing career, but it was also filled with the challenges of his time. These challenges persist, even in our times,” said David Henderson, MD, psychiatrist-in-chief at Boston Medical Center and professor and chair of psychiatry at BUSM.

Branson and other seminar presenters acknowledged that conditions have improved for Black academics, researchers and practitioners in the psychiatry fields, but that obstacles still remain. Branson said that Blacks are under-represented in fields like neurology. The 2021 U.S. Census estimated Black or African Americans at 13.4 percent of the U.S. population. But Branson cited an American Academy of Neurology 2020 Insights Report that showed Black or African Americans comprise just 2.8 percent of U.S. neurologists, with an average salary nearly $20,000 less than their white or Asian American counterparts.

“He had an amazing career, but it was also filled with the challenges of his time. These challenges persist, even in our times,” said David Henderson, MD, psychiatrist-in-chief at Boston Medical Center and professor and chair of psychiatry at BUSM.

Henderson called Fuller a triple threat, a neurologist, pathologist and psychiatrist who had an impact on psychiatrists and researchers practicing in those fields, regardless of their race.

“(Fuller) was resilient and persistent as an academic clinician and as a pathologist and a scholar. And what really impressed me, amongst his many accomplishments, was his drive to succeed and to self-educate,” said Christopher Andry, M. Phil, PhD, chief of pathology & laboratory medicine at Boston Medical Center and chair of pathology & laboratory medicine at BUSM.

Henderson said it’s difficult for the University to go back and correct the wrongs of 100 years ago, but that there’s been a significant effort to address them in the present day.

Since 1969 the American Psychiatric Association has given out an award in Fuller’s name to a psychiatrist who has significantly improved the quality of life for Black people. Henderson was a 2007 recipient of the APA Solomon Carter Fuller Award for his work in Africa and Asia training psychiatrists. While doing that work, he also was researching the roots of mental health issues in ethnic U.S. populations.

In 1972 the Commonwealth of Massachusetts built the Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center on the BU Medical Campus.

Fuller biographer Mary Kaplan spoke at the BUSM seminar on a drive to have Fuller’s life documented in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

But to many of Fuller’s grandchildren, his accomplishments were largely overshadowed by that of his wife Meta, a well-known sculptor, according to grandson John Fuller.

“When I was a youngster, I only knew my grandfather as Grandpa and we didn’t know of his accomplishments until later,” Fuller told the seminar.

“It’s a proud day for the family, that BU has recognized my grandfather,” said David Fuller.

Access, research and treatment challenges for Blacks and people of color

“We have a bias and disparity in terms of health care and access to health care (that) exists across the life course, (and) starts even before babies are born,” said Goldie Smith Byrd, PhD, director of the Maya Angelou Center for Health Equity and professor of social sciences and health policy at Wake Forest School of Medicine. “As we age those disparities grow get even larger.”

“Some of the negative racial interactions in Fuller’s experience, continue today in the Black experience in health care, and research has shown that Alzheimer’s disease is disproportionately impacting Blacks and people of color,” said Goldie Smith Byrd, PhD, director of the Maya Angelou Center for Health Equity and professor of social sciences and health policy at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

“African Americans and Hispanics … are more likely to have Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia … because we have greater familial (genetic) risk, we have more limited health care access, and later or no diagnosis,” Byrd said in the seminar’s keynote presentation. Other populations like Native Americans and Asian Americans are being studied but even less is known, she said.

“We have a bias and disparity in terms of health care and access to health care (that) exists across the life course, (and) starts even before babies are born,” said Byrd. “As we age those disparities grow get even larger.”

Byrd believes the COVID-19 pandemic really highlighted the impact that lower incomes and decreased access to health care can mean to prevention and treatment.

That disparity exists on the research side as well, where African Americans and other groups were being left out of medical trials.

Some of it is a reluctance of those groups to participate due to an inherent distrust of medical research in the Black community given past abuse like the Wake Forest eugenics studies and the Tuskegee syphilis study, Byrd noted. She said researchers also need to understand the culture of the group they are seeking to engage.

Byrd said her organization has been striving to rebuild trust in North Carolina Black communities by working with family units and through faith groups.

“Trustworthiness requires us to look at ourselves as providers, as researchers, as trialists, to see if we are making … the appropriate, culturally relevant connections,” said Byrd, “as well as giving back to that community by communicating test results and support.”

It’s Personal

“This is an underrepresented community. Not that attempts haven’t been there, but they haven’t been able to influence people and rally to get things done,” said Valerie Nolen, senior facilitator for the BU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center’s (BU ADC) Community Action Council and a diversity, equity and inclusion partner with BUSM’s department of neurology.

Valerie Nolen knows all about communication and trust. She is the senior facilitator for the BU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center’s (BU ADC) Community Action Council and a diversity, equity and inclusion partner with BUSM’s department of neurology.

Nolen didn’t know anything about Alzheimer’s before her mother called her home in 2002, saying “Something is wrong with your sister.”

One look and Nolen could see that the sister she knew was gone.

Nolen, a career businesswoman, started to educate herself and quickly found she knew nothing about the disease – it just hadn’t been talked about in her family or community. Nolen hadn’t even heard about Fuller or his Alzheimer’s research until she traveled to Europe and asked about the disease there.

“This is an underrepresented community. Not that attempts haven’t been there, but they haven’t been able to influence people and rally to get things done,” said Nolen.

She joined BU ADC in 2005 and has made it her mission to educate the Black community on the importance of participating in trials and getting tested for Alzheimer’s.

“I think when people hear about Alzheimer’s research, they think it’s all about taking a new drug or medicine,” said Budson. “Or that they have to have Alzheimer’s to participate.”

“Although we do have some research like that, there’s a lot of research going on that healthy older individuals can participate in, and a lot of it has no medicines at all,” said Budson.

Nolen has the same message for everyone who balks at testing or supporting the research whether in the neighborhoods of Boston or on Capitol Hill.

“I understand you’re apprehensive, but I also understand how important it is to confront our fears, recognize them, find someone to talk to about it,” she said. “You can talk to me, and then we can go forward.”

Royisha Young, the research coordinator at the BU ADC, said the center was established in 1996 and is one of 37 federally funded Alzheimer’s disease research centers located around the country. Its mission is to reduce the human and economic costs of the disease through research, care and education.

“(We) give numerous educational talks in the community encouraging brain health and healthy lifestyles,” she explained. Center staff also go into the community to recruit people to participate in various research trials they are conducting like genetic studies, caregiver research and imaging.

“These help us to learn about how brain images can provide more information about diagnosing and detecting Alzheimer’s disease early on when treatments are most effective,” said Young.

The effect of AD on the family unit

“A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease will have a significant impact, not only on the individual diagnosed, but also their family unit,” said Lola Baird a licensed independent social worker at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System.

“A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease will have a significant impact, not only on the individual diagnosed, but also their family unit,” said Lola Baird a licensed independent social worker at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System. The rate of Black Americans diagnosed with Alzheimer’s has more than doubled since 1995, Baird said, with more than 9 million expected to be afflicted by 2036.

Baird’s research showed that prejudicial housing policies grouped Black people in communities with high crime rates. That created persistent long-term stress, which contributes to higher Alzheimer’s rates in those communities.

“Understanding the impact of sustained or continuous exposure to trauma on later life outcomes is important as our population ages,” Baird said.

A love of lifelong learning

Part of the legacy of Fuller is his dogged work to get an answer to a problem and his love of learning.

“Dr. Fuller’s life and legacy actually mirrors mine,” said Keith Josephs, MD, professor of neurology and neuroscience at the Mayo Clinic. Like Fuller, Josephs came to the U.S. from another country, Jamaica, to pursue his education. He received a master’s degree in Mathematics from the University of Florida, his MD from the Medical College of Pennsylvania, and a second master’s degree in Clinical and Translational Research.

Similar to Fuller’s research on Alzheimer’s, Josephs meticulously researched a condition, Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech, whose symptoms, slow speaking rate, articulatory distortions and sound substitutions and others, were found in other, more studied, syndromes. Patients often lost the use of their limbs and died within a decade of onset, Josephs’ explained.

Josephs saw his rise from a community college in Miami to multiple degrees and a professorship at the Mayo Clinic as riding a wave.

“It is something about the inner motivation, wanting to climb this ladder, to be better and better,” Josephs said. In his overview of his career, Josephs described his approach as one of constant questioning and diligent pursuit of the answers, whether it was in a classroom, or in a clinical setting, or when doing research.

Is it enough to be motivated and talented?

“I think many Black psychiatrists today continue to struggle with our place in American psychiatry and our role,” said Steven Starks, MD, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Houston College of Medicine.

But a panel discussion of the barriers facing Black psychiatrists, neurologists and pathologists, found that desire and talent were not enough, even though nearly 90 years had passed since Fuller resigned after being passed over for promotion.

Steven Starks, MD, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Houston College of Medicine sees Fuller’s story as one of optimism in the face of challenge. But he also believed that the same obstacles Fuller faced over promotion, pay equity and opportunity in research and other areas, still existed.

“I think many Black psychiatrists today continue to struggle with our place in American psychiatry and our role,” said Starks.

Speaking as a panel member discussing the challenges and opportunities facing Black people seeking promotion in academia, Henderson believed that a lot had been done in the past 90 years, but he said there was a lot more to do.

“There has been progress, but I think we have to take a leap here, we really have to take big, big steps,” he said. “Everybody has been trained on implicit bias now. Every institution has supported implicit bias and there’s training and training yet we still have reports of bad actors and an unfriendly environment for people of color.”

Altha Stewart, MD, another recipient of the Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller Award and a senior associate dean for Community Health Engagement and associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Tennessee, said, “Change cannot just come from the Black community or other people of color.

“I think to be more welcoming, everybody’s got to carry their load. No one should expect that people of color, especially Black people, need to paint the picture of what the next step is you need to do,” she said.

“I’m actually pleased to see that the environment is changing in some ways and that there’s an effort and a desire (to talk) about inclusivity. It’s hopefully for most people a genuine thing,” said Teshamae Monteith, MD, an associate professor of clinical neurology at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine.

“Inclusivity is super important for underrepresented groups, but I think as you change the culture and start really moving these inclusivity initiatives forward you’ll find that there are many people that feel this way,” said Monteith.

“We know there are a lot of challenges,” said panel moderator Michelle Durham, MD, a clinical associate professor of psychiatry and vice chair of education in the BUSM department of psychiatry.

“But I think the list is long for opportunities to make this better … There are many more ways to improve the system for Black people and people of color on the academic side, the health care side and for society as a whole,” said Durham. “We need everybody on this journey for equity in all institutions.”

Learn more about the seminar.

View all posts