Trailblazing BU Alum Gets a Gravestone 125 Years after Her Death

Rebecca Lee Crumpler (MED 1864), the first Black woman to graduate from a US medical school, and her husband, Arthur, were buried in unmarked graves at the back of Fairview Cemetery in Hyde Park, Mass. They received headstones last month, thanks to fundraising by a local group and donations from across the country. Photo by Cydney Scott

Rebecca Lee Crumpler (MED 1864), the first Black woman to graduate from a US medical school, and her husband, Arthur, were buried in unmarked graves at the back of Fairview Cemetery in Hyde Park, Mass. They received headstones last month, thanks to fundraising by a local group and donations from across the country. Photo by Cydney Scott

Rebecca Lee Crumpler (MED 1864) was a trailblazer, the first Black woman to graduate from a US medical school. Born in Delaware in 1831, she moved to Charlestown, Mass., in 1852, and after the Civil War, moved to Virginia to tend to former slaves who were refused treatment by white doctors. She went on to publish a medical book (one of the first Black physicians to do so), which was notable for its clear messaging about women’s health. She died in 1895 of fibroid tumors.

But despite Crumpler’s accomplishments, she has been buried in an unmarked grave in Fairview Cemetery in Hyde Park, Mass., for 125 years. She was written about in history books and her house is a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, yet it was nearly impossible to find her final resting spot.

Melody McCloud (CAS’77, MED’81), an OB/GYN at Emory University Hospital, says Crumpler’s journey to medical school was a phenomenal accomplishment. Photo courtesy of McCloud

Melody McCloud (CAS’77, MED’81), an OB/GYN at Emory University Hospital, says Crumpler’s journey to medical school was a phenomenal accomplishment. Photo courtesy of McCloud

That changed last month. On July 16, the pioneering physician and her husband, former slave Arthur Crumpler, who was buried beside her, finally received proper granite stones, thanks to fundraising by local groups and donations from across the country.

Melody McCloud (CAS’77, MED’81), an OB/GYN at Emory University Hospital and founder and medical director of Atlanta Women’s Health Care, spent years researching Crumpler’s legacy and was thrilled when she learned that gravestones would at long last mark the final resting place of Crumpler and her husband. McCloud says Crumpler’s journey to medical school was a phenomenal accomplishment, as she encountered both sexism and racism. “She must have faced hell in her professional life,” McCloud says. “Some of the hospitals wouldn’t grant her admitting privileges, some of the pharmacists refused to fill her prescriptions, some people joked that the ‘M.D.’ behind her name stood for ‘mule driver.’ What she accomplished was exemplary.”

A pioneering alum

Raised by an aunt who tended to sick neighbors, Crumpler worked as a nurse in Charlestown before enrolling in Boston’s groundbreaking New England Female Medical College. When she entered in 1860, there were about 54,000 doctors in the United States. Only about 300 were women, and none were Black. Crumpler graduated four years later, and a decade after that, the college merged with Boston University.

After graduation, Crumpler moved with her second husband, Arthur (who had escaped slavery) to Richmond, Va., and began work at the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency created at the end of the Civil War to help recently freed slaves secure food, housing, and medical care. Although she encountered prejudice and hostility as a Black female doctor, she persisted, and soon discovered her life’s mission: treating illness in poor women and children.

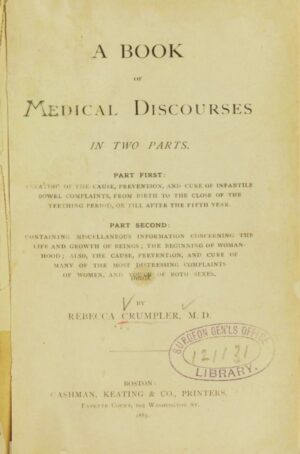

Title page of Crumpler’s A Book of Medical Discourses (1883). Photo courtesy of Internet Archive

Title page of Crumpler’s A Book of Medical Discourses (1883). Photo courtesy of Internet Archive

Upon the couple’s return to Boston in 1869, Crumpler opened her own medical practice at her home at 67 Joy Street in Beacon Hill (now a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail). She published A Book of Medical Discourses in 1883, which is believed to be the first medical text written by a Black author. Scientific American describes it as a forerunner to the famous What to Expect When You’re Expecting; it covered topics like pregnancy, nursing, teething, and other ailments that come up during the first five years.

Crumpler died in 1895 of fibroid tumors, at age 64. Historians believe that she probably wasn’t aware that she was the first Black female graduate of a medical school. She was buried at the then-new Fairview Cemetery (the couple had moved to Hyde Park about 15 years before her death). Arthur, a blacksmith and porter, was buried next to her when he died in 1910. They were among the first people buried in the cemetery, and many of them do not have headstones, according to a blog post by the Friends of the Hyde Park Branch Library.

A legacy that lives on

McCloud’s MED class was only about 10 percent Black, she says, and she didn’t know about Crumpler when she graduated in 1981. She first learned about Crumpler as a young doctor starting out in Atlanta. She joined the Rebecca Lee Society, named for Crumpler, one of the first medical communities for Black women. McCloud later began writing about Crumpler so she would get the recognition she deserved.

In 2013, McCloud was casually talking with a member of BU’s Alumni Relations team and learned that MED sometimes decorates its hallways with historical exhibitions. McCloud knew just who they should feature next. It is now a permanent exhibition.

In 2019, McCloud contacted Virginia Governor Ralph Northam to urge that Crumpler be honored for her work caring for freed Blacks in Richmond, and he declared National Doctors Day (March 30) “Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler Day.”

Then in February 2020, McCloud got a phone call that solidified a cause she had been fighting for for almost four decades. Vicky Gall, president of the Friends of the Hyde Park Branch Library and a history lover, had come across Crumpler’s name while reading a list of Hyde Park residents on Wikipedia, according to the Boston Globe. Gall learned that the Crumplers didn’t have a gravestone and was working to remedy that. The Friends group started a fundraiser, securing donations from the four Massachusetts medical schools (including BU), a recruiting class from the Boston Police Academy, and private donors across 21 states.

When McCloud heard the news that granite gravestones were being erected, she says, “I was so excited, oh my God.” She couldn’t attend the ceremony in person, but she reached out to a friend who works at NBC to see if they would be interested in covering the story, given all the eyes on the Black Lives Matter movement and the question of whether Confederate monuments should be allowed to remain. She received a call back from a producer at NBC Nightly News: they wanted to do a story.

Representation matters

While Crumpler devoted her life to addressing health inequities among people of color, the coronavirus pandemic has proven that much progress is still needed. Reports show that long-standing systemic health and social inequities have put many minority groups at an increased risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19. According to a recent editorial by the dean of Weill Cornell Medicine, studies show that there is greater trust between doctors and patients when they are the same race or ethnicity, leading to increased engagement on both sides and a better following of the doctor’s recommendations. But in 2018-2019, only 6 percent of medical school graduates were Black, and only 5 percent of active US physicians were Black. In addition to a host of other efforts, MED recently endowed a scholarship in Crumpler’s name, awarded to students from underrepresented groups, with preference given to Black women.

Role models are important, especially for people of color, says McCloud. She talks about her fond memories of Doris Wethers, her Black female pediatrician. “That was rare in the 1960s,” she says. “I used to love to go to her office. I knew she helped people feel better. She was instrumental in me wanting to be a physician.”

McCloud remembers when her high school history teacher told her mother to make sure she was enrolled in typing, “‘because Black people don’t become doctors,’ she said. But I knew better, because I had Dr. Wethers. It’s so important to see people who look like you doing things you want to do.”

And Rebecca Lee Crumpler did it first.

This BU Today story was written by Amy Laskowski. Photos by Cydney Scott.

View all posts