CTE Found in Dead College Football Player: First evidence of brain disease in athlete with no concussions

In April, University of Pennsylvania offensive lineman Owen Thomas complained to his parents that he was feeling stressed. He said he was worried that he would fail some of his college courses. The next day, Thomas, who had just been named captain of Penn’s football team, was found dead in his apartment, where he had hanged himself. His parents and friends were baffled. They had known him as “vibrant, a leader, and a problem-solver.”

The 21-year-old junior, and his two brothers, had played football since childhood. Two weeks ago, Thomas was diagnosed, postmortem, with mild chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), an Alzheimer’s-like brain disease associated with repetitive head trauma and seen, most notably, among a number of former National Football League players, at least two of whom took their own lives.

(to view the video, click here)

The diagnosis was made by Ann McKee, a School of Medicine associate professor of neurology and pathology and one of four codirectors of BU’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (CSTE), who is also director of neuropathology at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in Bedford, Mass. It was independently confirmed by neuropathologist Daniel Perl, of Mount Sinai Medical Center, in New York. McKee and other BU researchers emphasize that it’s impossible to definitively link Thomas’ suicide to CTE, but they note a pattern of suicide and suicidal behavior in CTE victims, such as NFL stars Andre Waters and Terry Long.

“I knew there was a missing piece,” says Thomas’ mother, the Rev. Katherine Brearley, of Allentown, Pa. “No one has given me even a hint of an explanation why Owen, at the drop of a hat, would kill himself. It’s out of all proportion and totally out of his character.”

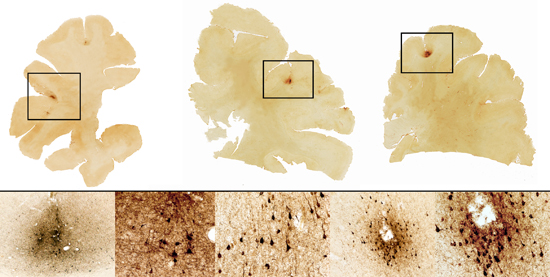

Top row: Brain sections showing dense tau protein deposition in multiple areas of frontal cortex (boxes). Bottom row: Microscopic images showing large numbers of tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles (dark brown spots) in the areas of damage.

Top row: Brain sections showing dense tau protein deposition in multiple areas of frontal cortex (boxes). Bottom row: Microscopic images showing large numbers of tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles (dark brown spots) in the areas of damage.

Thomas’ diagnosis is unique in two ways: he is the first active college athlete to be found with the disease, and unlike other known victims of CTE, he was never diagnosed with a concussion. However, Thomas had been a lineman and a linebacker, positions that typically involve multiple hits to the head during every game and practice, with estimates of approximately 1,000 hits per season or more. As part of its research, the CSTE team has been studying the role of subconcussive hits in the development of CTE.

CTE, believed to be caused by repeated jolts to the head, is characterized by the buildup in the brain of the toxic protein tau, which impairs normal brain functions and eventually kills brain cells. Early symptoms, which may not become evident for years, include memory impairment, emotional instability, erratic behavior, depression, and problems with impulse control. Dementia waits in the wings.

“This finding emphasizes that the early stages of this disease can start at young ages even in the absence of well-documented concussions,” says McKee. “It’s more evidence that we urgently need more research on CTE to fully understand the severity and frequency of brain trauma that can trigger this response, so that we can implement rule and equipment changes to protect our athletes.”

Thomas joins a growing list of active and retired football players, and other contact sport athletes, who have been diagnosed with CTE after their deaths. McKee has found CTE in 12 of 13 former professional football players, as well as in amateur football players, professional boxers, and hockey players.

“We will never truly know what led Owen to take his own life,” Brearley says. “However, knowing that he had a brain disease that could have had an impact on his emotional state, cognitive functioning, and impulse control brings us some solace.”

CSTE codirector Robert Cantu, a MED clinical professor of neurosurgery, who wrote the original return-to-play guidelines for concussions in the 1980s, says brain trauma guidelines similar to the pitch-count regulations now used in Little League baseball need to be developed for youth football, which is played by one in eight boys in America. A number of states, including Massachusetts, have adopted legislation mandating return-to-play rules and brain trauma education for all coaches, athletes, and parents.

“We count the pitches of every baseball player to ensure a small number do not develop shoulder and elbow problems,” Cantu says, “and yet we don’t count how often children get hit in the head playing football, even though it can lead to early dementia or possibly depression and suicide years later.”

Brearley says she had never heard of the progressive brain disease when former college lineman and retired professional wrestler Christopher Nowinski, another CSTE codirector, called to see if the family would be willing to donate their son’s brain. Brearley agreed, but didn’t think they’d find anything.

“I’m astounded,” she says. “We set off down this path of playing football without realizing the risks he was putting himself in. You don’t send someone back in with a bone injury. If I’d even had a clue that he was risking his brain, I’d have said absolutely not. It’s so painful to think about.”

In the wake of their son’s death, Owen Thomas’ father, the Rev. Tom Thomas, who himself played college football, signed up with CSTE’s research registry, run by codirector Robert Stern, which tracks former players over their lifetime and will study their brains and spinal cords upon death. “If Owen hadn’t taken his life now,” Thomas says, “I’m concerned by how his life would have turned out given the progressive nature of CTE.”

Brearley and Thomas are now advocating for greater awareness among coaches, trainers, and parents, particularly at the college level.

“Owen was a leader and a wonderful person,” Brearley says. “It would be an honor if he is able to trigger changes in college football practices. Our hope is that the Ivy League schools will step up and play a leadership role in this issue.”

This BU Today story was written by Caleb Daniloff. He can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu. The video is by Devin Hahn and Alan Wong. They can be reached at dhahn@bu.edu and alanwong@bu.edu.

Read more about BU’s research on CTE and its effects on changes in the NFL and youth sports here.

View all posts