Professionalism & Ethics in Medicine Lecture Addresses Pandemic’s Ethical Issues

The second annual Alan and Sybil Edelstein Professionalism and Ethics in Medicine Lecture, held virtually on Nov. 30, addressed the ethical issues at the heart of the pandemic. It was sponsored and moderated by David Edelstein (MD’80), a member of the Dean’s Advisory Board at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine who serves as director of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital.

“As we thought about topics for this year’s lecture, what stood out was how the COVID crisis intensified the challenges of doctor/patient ethics, particularly in areas such as autonomy, equity, privacy and trust,” said Marcia Edelstein Herrmann, MD’78, in introducing the lecture.

The panel of experts included Ravin Davidoff, MBBCh, professor of medicine and executive medical director at Boston Medical Center (BMC); Michael Ieong, MD, assistant professor of medicine and BMC medical director of the medical intensive care unit; Jessica Pisegna, PhD, assistant professor of otolaryngology and BMC section chief of speech and language pathology; David Hamer, MD, professor of medicine and global health and BMC infectious diseases attending physician; and Jacob Bloom, MD, a BMC fourth-year otolaryngology-head & neck surgery resident.

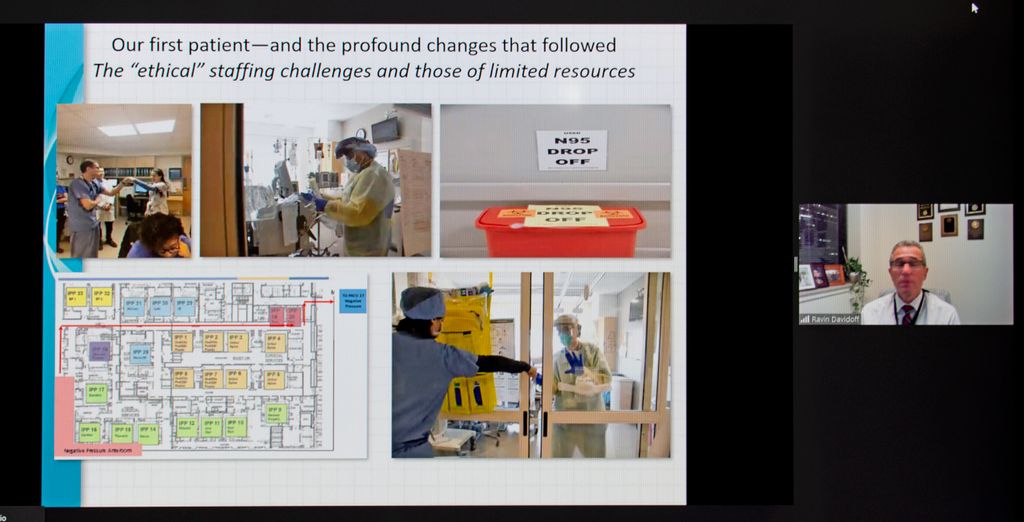

The COVID-positive patient census at BMC skyrocketed from 22 patients on March 24, 2020, to 121 patients in just eight days, and reached 219 on April 9. It marked a shift in focus from the individual to the overall public good and “maximizing survival at the community and societal level,” said Davidoff and at this early time, central state coordination had not yet been established.

“We knew there were going to be bed shortages, (but) the overall system was very slow to respond and plan for that,” said Ieong.

Scarcity of medical and personal protection supplies, no vaccines or proven medications and an inadequate system of testing exposed the social inequities in health care, said Davidoff, with Blacks and Hispanic/Latinx accounting for 76 percent of BMC’s inpatient admissions, double the number of inpatient admissions of people who were homeless compared to the previous year, and Blacks accounting for nearly half of COVID deaths at BMC.

Rationing of supplies, medicines and medical equipment seemed inevitable and hospital leaders and staff determined decisions would be made with the guiding principles of equity, accountability and transparency. For example, to address a critical ventilator shortage, the hospital formed a response team who would take the decision-making on who would get a ventilator out of the hands of the primary care teams.

“We had a plan in place and thank God — thank God — we never had to deliver on that approach,” said Davidoff.

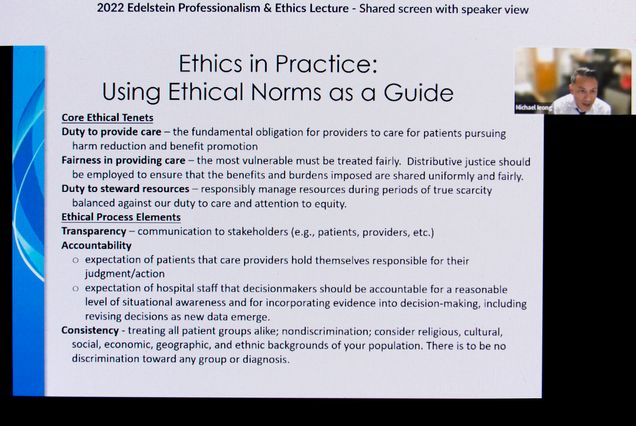

Ieong said the medical teams felt there was a fundamental obligation to provide care for all people.

“Fairness was a big issue,” he said, and communication was the key to transparency and accountability.

When vaccines became available, Davidoff said the team had to decide which health-care workers were prioritized.

“We very publicly talked about how we were making the decisions about which employees would be in the first wave…and how we would roll that out,” said Davidoff.

Early on, BMC started training additional personnel of all specialties to deliver intensive care unit (ICU)-level care. Jacob Bloom was a new intern when he was asked to help in the ICU.

“I thought if there was ever a time to stand in there and help out, not just the patients in front of me but society as a whole, this was my time to contribute,” he said.

Pisegna’s specialty, speech therapy, came with high risk. Her teams worked up close with COVID patients who had trouble speaking, swallowing, or who had throat surgery and tracheotomies. They had to triage patients based on the severity of their malady, with more severe cases seen in person and others remotely. When the hospital needed beds, a patient who only needed a swallow test to be discharged was prioritized, said Pisegna.

Hamer said a crowdsourcing approach helped BMC survive. They’d bulk-buy drugs they thought they’d need. Clinicians were on call 24 hours a day to consult with infectious diseases specialists on the wards regarding who should receive the limited amounts of a certain drug to help slow the progression of COVID-19, he said.

“There’s some really challenging ethical decision-making in this process,” Hamer said. They developed a protocol for identifying patients who were most likely to benefit.

“It took a lot of effort to make sure the right patients received treatment,” Hamer said. “They did a great job.”