Sandro Galea Aims to Change the Conversation around Health with New Book

SPH dean says more focus should be on preventing, not treating

In his provocative new book, Well: What We Need to Talk about When We Talk about Health, Sandro Galea, dean of the BU School of Public Health and Robert A. Knox Professor, argues that as a society, we’ve been thinking about health the wrong way: we conflate the concept of health with the practice of medicine and place too much emphasis on treating illness rather than preventing that illness in the first place.

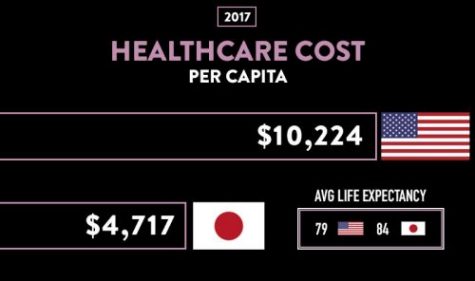

He cites study after study demonstrating that our country’s health output per dollar is worse than any of our peer countries. We’re spending money on “ineffectual, finger-wagging efforts to modify behaviors, then later on medicine to help us after we get sick,” says Galea.

Instead, he says, we need to think more deeply about the interconnected forces around us—from money and power to love and hate, compassion, fairness, and justice—and how they can lead to sustainable health and wellness.

“Our health is not defined by things like seeing doctors or taking medicines or getting in our 5,000 steps a day,” he writes in the introduction to Well (Oxford University Press, 2019). “Rather, it’s defined by the full spectrum of our life circumstances, from the families we come from to the neighborhoods where we live to the people we see and the choices we make.”

In other words, our health is both governed by, and limited by, the world we live in.

BU Today spoke with Galea about his book and his goal of shifting our national conversation about health to better focus on the forces that make us healthy. He will speak at a book signing, free and open to the public, on Friday, May 3, at the Harvard Coop.

BU Today: How did the idea for the book come about?

Galea: Well is a combination of old and new. It is partly an expression of ideas that have long simmered in my mind and partly a response to changes in our national conversation which are fairly recent, and which have, I would argue, created an opening for talking about health in a new way. The book is divided into 20 chapters, each exploring one of the core forces that shape health—forces like power, money, politics, place, love and hate, pain and pleasure, and choice. These factors are at the heart of whether we get sick or stay well, yet, historically, they have not always been part of the health conversation. This has begun to change, however, in the last few years, a process which has been informed by the unique social and political shifts of our present moment. Well is an attempt to add to this conversation, with the hope that changes to how we talk about health will lead to changes in how we structure our society, to ultimately create a world that is geared toward generating health.

You write that we have been mistaking health care for health, placing a premium on treating illness rather than preventing it in the first place. How have we gotten it so wrong?

As individuals, our experience of health tends to follow a similar pattern. We do what we can to live healthy lives, and when we get sick, we see a doctor who prescribes treatments, which, hopefully, cure us. It is understandable, then, that we tend to think of health as we experience it—almost like it is a math equation (disease plus medicine equals health). But health is far more complex than this. It is more like a web of overlapping, constantly shifting influences, which include our environment, income, education, and social identity. Because we see health through a curative lens, when we think we are talking about health, we are often actually talking about health care, and when we think we are investing in health, we are actually investing in doctors and medicines, rather than in improving the socioeconomic conditions that truly shape health. We need to correct this mismatch by investing in the core drivers of health the same way we currently invest in treatments.

You say economic justice is imperative to improving health and suggest ways to achieve that: expanding the earned income tax credit that reduces the tax burden for low-income Americans, raising the estate tax to pay for funding of public goods, and pushing for a single-payer healthcare system. But given the political climate, are any of those realistic?

We cannot be healthy if we cannot afford the resources that generate health—such as nutritious food, quality education, a good home in a safe neighborhood, or the simple peace of mind that comes with having enough money to handle contingencies. Ensuring all can access these resources means tackling the growing divide between those with an excess of economic opportunity and those with none. To ensure this access, we must pursue economic justice at the policy level.

Our politics is in a state of flux, with a range of voices competing to define the agenda for the coming decades. We have already seen how forceful advocacy can shift the window on what is regarded as feasible in the political realm. Many of the Trump administration’s policies, for example, might have been considered not merely unrealistic, but unthinkable just a few years ago—such as the policy of family separation. But just as policy can be shifted in a harmful direction, it can also be shifted towards steps that will improve health through social and economic justice. Conversations around a more progressive tax policy, for example, have informed several campaign platforms in the 2020 presidential race. The roots of tangible changes lie in changes to the conversation, and it is never too soon to work towards these shifts.

You’re optimistic that we can begin improving the forces that keep us healthy—where do you see reason for hope?

There is ample reason to hope we are moving, collectively, in a healthier direction by addressing the root causes of health. This movement reflects decades of work by health advocates, as well as public response to the dramatic, paradigm-shifting events of the Obama-Trump years. Take one of the core threats to health in the contemporary United States: gun violence. For a long time, it seemed like the politics around guns would never change, that mass shootings would continue to occur and opponents of common-sense gun safety laws would continue to block all meaningful reform. In recent years, however, we have seen the rise of a student-led gun safety movement which has begun to exercise real power and has the potential to completely change the status quo around guns by addressing the problem at the political level. At the same time, it is now common to hear gun violence called what it is: a public health crisis. It was not always this way. That we now see shootings as a threat to public health is a testament to many years of trying to change the terminology around guns, so that we could eventually change thinking and apply public health solutions to this problem, which we have now begun to do. This is what can happen when we look past the surface of health challenges to address their root causes.

You talk about the need to shift our focus away from individual decision-making and toward a broader view of choice. But in a culture that prizes individualism, is that possible?

There is a myth in our culture and politics that individual freedom is invariably at odds with collective actions aimed at promoting health. Smoking bans, food portion controls, gun safety legislation—all have at one time or another been pointed to as evidence of a “nanny state” bent on hampering individual freedom. Yet we cannot be free if we are sick. We cannot be free if we are injured or dead. Choice shapes our risk of falling prey to these outcomes, but all choices are not created equal. We like to think our health is in our individual hands, yet it is high-level choices—such as political choices to regulate dangerous products, or corporate choices to sell them—that truly decide how healthy we are able to be and how much freedom we can enjoy. Making the case for a broader view of choice means talking about these different kinds of choice and how efforts once mischaracterized as intrusive are actually ways to lessen the monopoly on choice enjoyed by the powerful and give more freedom to the individual and her choices—the freedom that comes with health.

You stop short of giving a blueprint for how to improve the conditions that shape health, saying instead that you hope others will build on the framework you set out. Do you see any candidates in the 2020 presidential race who are doing this?

The conditions that shape health are everywhere in the 2020 political debate. From economic justice to confronting America’s fraught racial history to addressing the generation-defining issue of climate change, the political conversation touches on many subjects that matter for health. It is important to note, however, that while health is intimately tied to politics, it is ultimately not a political issue. All of us wish to be well. All of us wish to build a world where our children can be healthy and safe. Politics is a means to this end; a healthy politics leads, ultimately, to healthy people.

Well is peppered with references to pop culture, like The Devil Wears Prada and Star Trek. Why was it important to cite pop culture?

Health is closely linked to culture. Books, films, and music reflect the core conditions that shape our society and our health. They also provide a common frame of reference, making them especially helpful when one is trying to illustrate an idea. Star Trek, for example, has long been interested in issues of tolerance, diversity, and how we can create a future that is radically better than our past—all of which link to the themes of Well. As for The Devil Wears Prada—it is hard to find a better example of how corporate choices shape our world than a parable of high-fashion tastemakers deciding next season’s trends from an exclusive New York office. Plus, who does not like Meryl Streep?

Speaking of pop culture, you’ve even put together a Spotify playlist to accompany the book. How did you come up with the idea for that?

As I wrote the book, I found that with each chapter, a new song would get stuck in my head. Generally, these songs would link to the theme of the section I happened to be working on. Some were silly, some serious, some outright inspiring. Eventually, I began writing them down, and the playlist was born. It started as a bit of fun, but now I wonder how I ever released a book without one.

Listen to the Spotify playlist for Well below.

Sandro Galea will be on Reddit I/AmA today, Friday, May 3, at noon ET, to discuss what we should think about when we discuss health and wellness on an individual, national, and global scale. Join the conversation and ask any questions related to health, wellness, and global public health.

Galea will discuss his new book, Well: What We Need to Talk about When We Talk about Health, on Friday, May 3, at a book talk and author signing at the Harvard COOP, 1400 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, at 7 pm. The event is free and open to the public. Register here. By public transportation, take an MBTA Red Line train to Harvard Square.

This BU Today story was written by John O’Rourke.