Zika Strikes Miami

SPH researcher: Florida outbreak “was only a matter of time”

On July 29, the Florida Department of Public Health reported the first localized cases of Zika virus in the United States, in Miami, Florida. Because the virus has been linked to microcephaly—babies born with small heads and neurological deficits—and to other syndromes like Guillain-Barré (a disorder where the body’s immune system attacks the nerves, leading often to temporary paralysis), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released an unusual—some say unprecedented—travel alert, advising pregnant women not to travel to Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood, where the virus was found.

David Hamer, a School of Public Health professor of global health, a School of Medicine professor of medicine, and principal investigator for the global infectious disease surveillance network GeoSentinel, has been tracking the current Zika outbreak from its earliest days. BU Today spoke to Hamer about the news from Miami, what this means for summer travelers, and the next steps for scientists studying Zika.

Caption David Hamer, a School of Public Health professor of global health and School of Medicine professor of medicine, has been tracking the current Zika outbreak. Photo by Cydney Scott

BU Today: What’s going on in Miami?

Hamer: They’ve found some people who have become locally infected, who have not traveled outside of Miami. And that seems to have triggered a house-to-house investigation, where they’re trying to identify people who have been symptomatic, or even those who have not been symptomatic, and testing them for Zika. And by doing that testing, they encountered 4 cases initially, and it has increased to 17. And several of those people were asymptomatic, so they discovered them by doing blood testing.

Did they get it from a mosquito in Miami or from something else in Miami?

I think the public health authorities are fairly confident that it’s from a locally infected mosquito, as opposed to sexual transmission.

Were you surprised to hear about these cases?

It was just a matter of time. The mosquitoes are definitely there in much of Miami, or much of Florida, for that matter.

Which mosquitoes are people worried about, and how far north can they go?

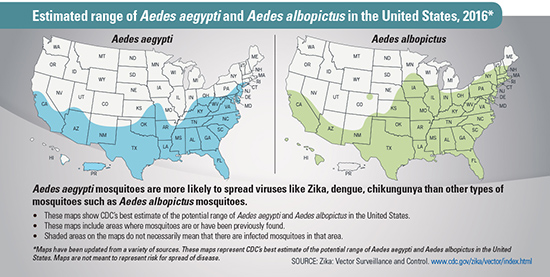

Everybody’s worried about both Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, but so far it seems like most of the transmission has been through Aedes aegypti. And its range seems to extend up to maybe Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana. It’s basically a few states in the South, and then it crosses over to Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, but not much further north. Whereas Aedes albopictus extends all the way up to Pennsylvania and New Jersey. It’s much more widespread across the United States.

What do we know now about sexual transmission?

It’s definitely an evolving story. There’s evidence of carriage of the virus in semen—I think there are some cases that have lasted a little more than two months.

I thought semen regenerated continuously. So why is the virus sticking around for so long and where is it actually staying?

I don’t really know. I’m not sure we really understand. The other question is: Is it hanging out somewhere within a woman in the genital tract also? And we don’t know. But now there’s definitely an interest in that, trying to understand where it’s carried and for how long.

Do you think that the sexual transmission might turn out to be a bigger factor in the spread of Zika than mosquitoes?

No, I think mosquitoes are going to remain the real major form of spread, but that sexual transmission is going to make it more complicated. I think there’s going to be a lot more data coming out soon to understand where it’s carried, what allows it to propagate, and how it persists.

Concern is focused on pregnant women or women thinking about getting pregnant, but Guillain-Barré is also an issue. Are other groups at risk? Should people cancel their travel plans to Florida?

I probably would not recommend that people change their travel plans, except to this one specific area within Miami. I think the people who should think twice are somebody who’s pregnant, somebody who’s planning to become pregnant in the next 6 to 12 months, or the significant other (the spouse or male partner) of that person. And that’s really it. We don’t know what the risk factors are for Guillain-Barré syndrome. It probably occurs in only a few people per thousand cases of Zika, so it’s a rare complication. And even though it’s worrisome and potentially dangerous, potentially even life-threatening, it tends to come on quickly and resolve quickly.

It sounds like there are still a lot of unanswered questions about Zika.

Yes, there’s a lot happening quickly. It’s exciting in a sad way, but I think we’ll see more. I think we’ll learn more, and then the real question is: are we going to see more? And I suspect we will.

This BU Today story was written by Barbara Moran.