The Addiction Puzzle

As part of a week-long series on addiction research, BU Today highlighted the work of Alexander Walley, School of Medicine assistant professor of medicine and the medical director of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s Opioid Overdose Prevention Pilot Program.

Drug or alcohol addiction affects nearly 23 million Americans and costs the United States an estimated $428 billion each year. Modern science has dispelled many misconceptions about the disease and scientists are working hard to find effective treatments. At Boston University, more than 100 researchers have been awarded over $130 million in addiction-related research and services grants since 2006, and faculty currently direct over 50 funded addiction-related research projects.

Still, many questions remain: why do some people become addicted and others don’t? Why are some recovering addicts able to maintain sobriety while others have chronic relapses? Does evidence-based research contradict what has been assumed to be effective screening and treatment programs? In what ways does addiction impact men and women differently?

Brigitte knew there was something wrong with her son. The day after Thanksgiving in 2011 he left their Foxboro home early in the morning, saying he wanted to get some Black Friday deals. “I knew something was up right then,” she says. After all, how many 21-year-old men care about sales at the mall?

When he returned that afternoon, her suspicions were confirmed. “I could just tell from his posture that he had been using,” she recalls. Brigitte (not her real name) had been shocked several months earlier to learn that her son was addicted to heroin. The rest of that day, she followed him around the house, unwilling to let him out of sight. At 1:30 a.m., she checked on him one last time. He was typing on his laptop and told her with a smile, “Mom, don’t worry. I’m too young to leave yet. I’m not going anywhere.”

A half hour later, his father was awakened by the sound of the laptop thudding to the floor. He checked, saw his son wasn’t breathing, and woke his wife and daughter in a panic. “We were all screaming at each other,” says Brigitte. “He looked totally lifeless. His lips and eyes were dark blue. It was horrible.”

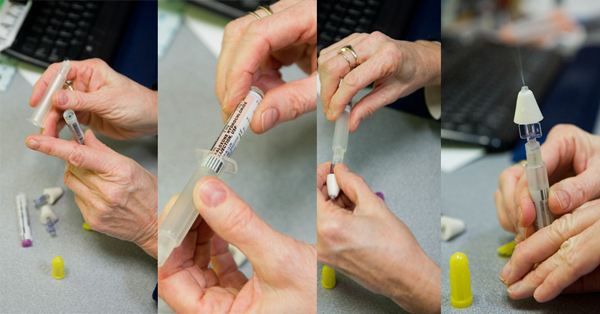

While her daughter called 911 and her husband started rescue breathing, Brigitte ran downstairs and grabbed a small pouch from the top of the fridge. It contained two doses of naloxone—often called by its brand name, Narcan—an antidote for heroin overdose. With shaking hands, she sprayed a dose into her son’s nose. Usually, naloxone reverses the effects of an overdose almost immediately, but because the heroin had been laced with fentanyl, an opioid that can be hundreds of times more potent than heroin, nothing happened. She gave him another dose, and when the EMTs arrived, they gave him another.

Her son was finally revived in the emergency room over an hour later, and recovered fully. “All the doctors were surprised we had the Narcan and knew how to use it,” says Brigitte. “It’s a powerful tool to have.”

Bringing people back to life

Narcan would not be so accessible to parents like Brigitte if not for Alexander Walley (SPH’07), a School of Medicine assistant professor of medicine and the medical director of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s Opioid Overdose Prevention Pilot Program. Through the program, the state distributes free naloxone kits to people likely to witness an overdose, and teaches them how to administer the drug. “Now they have this tool that they can use to literally bring people back to life, and that is a powerful experience,” says Walley. “It represents something that’s much bigger than just the medication.”

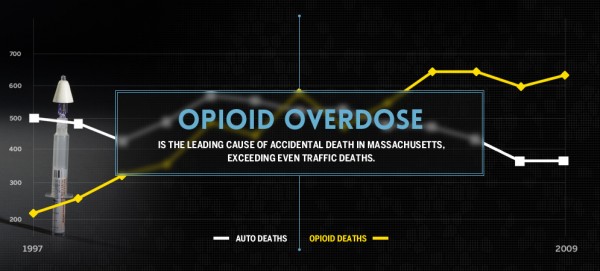

Opioid overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in Massachusetts, exceeding even traffic deaths. The overdose prevention program, which costs the commonwealth about $400,000 a year, has been a success: since it began in 2007 the program has trained more than 20,000 people to administer naloxone. They’ve used the drug to reverse more than 2,300 overdoses in Massachusetts, and the death rate from opioid overdose has leveled off.

The program has generated controversy, however, mostly from critics who argue that making the antidote widely available will encourage people to use heroin more recklessly, an argument that Walley dismisses. “For people who reach the point of overdosing, their judgment often has been hijacked by the drive to use,” he says. “Having naloxone around is not going to affect whether they’re going to use or not. It’s going to give them an opportunity to live longer, so they can go into treatment and try to beat their addiction.”

The program is unique in that it distributes a prescription medication to nonmedical personnel through trained public health workers under a standing order signed by Walley. Not all doctors like the idea.

“It’s a little edgy,” acknowledges Jeffrey Samet (SPH’92), a MED professor of medicine, a School of Public Health professor of community health sciences, and chief of general internal medicine at Boston Medical Center. “It’s giving a drug to someone to give to someone else, without ever seeing that someone else,” Samet says. “That’s just an uncomfortable feeling for doctors. But you step back, put on your public health hat, and say, ‘Well, it actually works.’”

“When this program started, it was not popular,” says Hilary Jacobs, director of the Bureau of Substance Abuse Services at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. “It was risky business for Dr. Walley to get involved. But he totally understands opioid addiction and is committed to helping this population. He’s been a great partner.”

Overdose is preventable

Walley became interested in addiction volunteering at a homeless shelter in Harvard Square as an undergraduate at Harvard. In medical school at Johns Hopkins, and during his residency in San Francisco, he witnessed firsthand the devastation caused by HIV and intravenous drug use, but also the great potential for healing. He came to Boston University to work with Samet and Richard Saitz (CAS’87, MED’87), an SPH professor of community health sciences and a MED professor of medicine, who also work to treat HIV and addiction through primary rather than acute care. In Boston, as in Baltimore and San Francisco, he watched as many of his patients suffered through—or died from—an overdose. “It’s such a waste and it’s devastating for families,” Walley says. “Overdose is preventable and we have effective treatments now for HIV and addiction. If we can keep people from dying from overdose long enough for treatment to work, their lives get better.”

Heroin has been a problem in New England for decades, but since opioid painkillers like OxyContin became more widely available in the 1990s, use and abuse has risen dramatically. In 2002, 884 people were hospitalized for opioid overdose in Massachusetts; by 2012 that number had more than doubled, to 1,857. Opioids are risky because they bind to receptors in the brain stem, which controls automatic processes such as blood pressure and respiration. Even at low doses, opioids decrease a person’s respiratory rate. Naloxone works by attaching to opioid receptors, kicking the opioids off, and reversing their effects. Naloxone is not addictive and will not produce euphoria, but in someone who has a high tolerance for opioids, it sometimes causes immediate withdrawal symptoms.

About 15 states now have naloxone distribution programs, and Massachusetts has been a national leader. One of Walley’s major contributions has been gathering data to prove that the system works. In a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published in the British Medical Journal in 2013, Walley and coauthors found that opioid overdose death rates were reduced by as much as 46 percent in communities where the program was implemented.

“The real success is if we can demonstrate it works and get it out there to the rest of the world,” says Samet. “Even if Alex goes out there and speaks about it, it just doesn’t have the same weight as being written up in a prestigious journal. That was huge.”

The Massachusetts program, under Walley’s medical direction, has also expanded the number of trained health workers who can distribute naloxone, and has helped put it into the hands of parents whose children are addicted to heroin. One of them, Joanne Peterson, founded and directs a support network for parents called Learn to Cope. In 2007, health workers began coming to the group’s meetings to train parents and distribute naloxone kits, but access wasn’t meeting demand. At Peterson’s request, the Department of Public Health and Walley authorized Learn to Cope to distribute naloxone, and the group now has 35 parents who train others. Since 2007, 16 parents have used it to save their children.

Peterson says that Walley’s help has been invaluable. “He just cares so much about this problem,” she says. “Think about the number of lives he’s saved. To me and other parents, he’s a hero.”

This BU Today story was written by Barbara Moran (COM’96.) She is a science writer in Brookline, Mass and can be reached through her website WrittenByBarbaraMoran.com.