Teaching Doctors How to Close Life’s Last Door

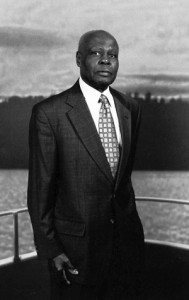

At age 78, Charles Swanigan could jog three miles at a stretch. One year later, with the prostate cancer he had battled for a decade spread throughout his body, he could hardly move. Just getting out of bed, he tells his doctor and two BU School of Medicine students paying him an autumn house call, wracks him with pain. View the video here.

Swanigan’s cozy Roxbury living room, with its fireplace and hardwood floor, has added a new piece of furniture: the hospital bed where Swanigan spends his days, shriveled arms protruding above the blankets. Eating has become an ordeal; the food will no longer stay down. The retired property manager, a divorced father of four, is cared for by his 20-year-old son. As Eric Hardt, a MED associate professor and a Boston Medical Center geriatrician, tells his students, the patient has endured a radical prostatectomy and “every drug known to man.” Yet Swanigan constantly clutches at new treatments that might prolong his life. “He’s going down fighting,” Hardt says.

Now, Hardt watches in the darkened living room as Lucas Thornblade (MED’12) checks Swanigan’s vitals, including his pulse. Thornblade’s examination roams far beyond questions of blood pressure and weight. “I was going to ask how you’re doing spiritually and emotionally,” he says. “I’m not sitting here worrying,” Swanigan answers. “It’s just, it’s not fun sitting here in bed.”

Hardt asks if any fellow parishioners from Swanigan’s church ever stop by. “A few,” says Swanigan. “I would have thought I’d have more, but…”

“This is kind of hard to talk about,” Hardt says, “but what if something unexpected and terrible happens?” Swanigan says he has a will. “If your heart were to stop beating,” Thornblade says, “some patients would prefer to have CPR and electric shocks given.”

“If that happened,” Swanigan asks, “how much of an extension is it? Just a few weeks, a month or so? I prefer not to be resuscitated and be in a lot of pain, if that’s what’s going to happen.”

“Thank you for sharing that with us,” says Thornblade, who helps Swanigan sign a do-not-resuscitate directive after the patient is assured that it won’t preclude necessary treatment.

“I heard you used to play clarinet. That was my father’s instrument as well,” says Thornblade. “Had a strong, strong desire to be a classical musician,” replies Swanigan, who studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music. “But it’s a tough field unless you want to go into teaching.”

“Any plans for Thanksgiving or the holidays?” the doctor asks.

“No,” says the patient, “nothing.”

********

Death is a toxic subject for doctors trained to heal, not prep their patients for the morgue. “No one wants a talk about it, because it doesn’t make for a good story,” says Matthew Russell, a MED assistant professor. Russsell (CAS’94, SPH’03) says end-of-life needs weren’t part of the curriculum during his medical training in the 1990s. A 2007 study of 51 oncologists by Duke University’s Center for Palliative Care (palliative medicine tries to relieve pain and suffering) found that even when cancer patients did open up about their sorrows, fears, or anger, the discomfitted docs doused the discussion three-quarters of the time.

That’s changing. MED’s old-fashioned house calls—after 150 years, the oldest such program in the country, Hardt says—are an important part of the palliative and end-of-life training in the school’s four-week geriatrics clerkship. (Clerkships are medical students’ temporary assignments in various hospital specialties.) Lectures instruct students how to be human beings as much as doctors, and that emotional connections with dying patients are as essential to good care as a stethoscope. The students also learn that while death is universal, how we die is tailored by our individual cultural and spiritual heritage.

Hardt, one of 15 docs on BMC’s geriatrics team, says the training grew partly from the observation that there are more people dying within the geriatric group than anywhere else in the hospital, including the intensive care units and oncology. The lesson has taken hold in medical schools nationally, where end-of-life care, including palliative medicine, is a growing trend, says David Longnecker, director of health care affairs for the Association of American Medical Colleges. Longnecker says that BU’s education in these fields is highly regarded.

The move has been fueled partly by reports such as a 2009 article in the Association of American Medical Colleges journal Academic Medicine, in which residents who’d been given bedside training with dying patients reported feeling more competent at end-of-life care.

Ebony Lawson (MED’12), who accompanied Hardt and Thornblade on the house call to Swanigan, says the visit showed her “firsthand how to approach difficult decisions.” She knows that a doctor inevitably deals with death, and she takes that discussion seriously. Still, she says, it’s emotionally difficult to talk about.

********

“How many of you have directly cared for a patient who died?”

Russell puts the question to the 10 students in the palliative care lecture he gives for the clerkship. A lone hand shoots up. “There is not a standardized dying patient,” he tells them. “People will have various symptoms to various degrees of intensity. We have to understand why this symptom is happening. The answer can’t be morphine, morphine, morphine in every case.” He warns that rote, inept treatment could accelerate the decline of a patient whose “goal could be making it the next few weeks to their granddaughter’s christening.”

The case studies that Russell cites are thick with medical jargon, but of his three Ms of medical examination, only the first, mechanism, probes a patient’s pathology and treatment. The second, meaning, explores what illness means to the patient herself—for example, asking what worries her about being nauseous. “It sounds weird, people don’t do it, and you don’t hear it all that much,” but mere yes-no questions about symptoms fumble the chance to be of real help, he says. He exhorts the students to remember who their patients are as people. “It’s the spouse of 60 years who’s going to lose a wife, the family who’s going to lose a matriarch. Our bread and butter is a patient and family’s worst day.”

The third M is a stunning word for a medical class—magic—all the more so for the humility it teaches a profession not known for being humble. The dying crave a miracle that will save them, Russell says, but healers must not oversell their powers in hopeless cases. “Remember the lesson of the Wizard of Oz,” he urges.

“There’s no place like home?” ventures a student.

“Oh, sh–,” says Russell with a laugh—he’d forgotten that famous moral of the story. “That’s not it. Another lesson.” He’s referring to the movie’s insight that the man behind the curtain is just a man. “We have to be mindful of our participation in that illusion of Oz,” he says. “Patients will often want us to be the wizard. You owe it to your patients to be true to what you know—which is limited.”

Underscoring the limits of care is the need to understand how a patient perceives them. Russell offers a case study of a 95-year-old demented woman who, near death, has stopped eating. Research confirms that her feeding tube will not prolong her life. Yet how do you suggest to her daughter that she order it removed? Students take a stab at the medical facts of the situation (“Unfortunately, she’s not going to be able to eat on her own,” tries one), but Russell reminds them that their doctor’s ear must hear the voice of the daughter’s heart.

“What is feeding someone? A proxy for something.” Love, suggests a student. Bingo, says Russell. “‘So don’t you ever tell me not to feed my mother, because she fed me every night.’ Food is love. You’re going to have to deal with that love thing. Make them know that what they’re not doing is love. I need to know that what I have done for my loved one matters and has mattered, because I want to know, at the close of their life, I have done everything I could have done. What needs to happen at that moment? An emotion. She needed to hear, ‘You did right.’”

********

In 2005, with help from an Aetna grant, Hardt developed a curriculum, called Culture, Spirituality, and End of Life Care, that attunes aspiring doctors to help patients of varying races, religions, and nations.

“We don’t have time to talk about all of America’s wondrous versions of racism,” he tells his class, making it clear that a doctor must never “lower the standard of care just because you don’t know the patient’s language.” Among his case studies is a Boston Globe story about a Buddhist family’s battle to keep their father on life support. Although his brain activity had flatlined, and “brain death equals death” in Western medicine, says Hardt, his heart continued beating, and to his family, that meant “the spirit still dwells in the body, so you can’t pull the plug.” Students struggle unsuccessfully with possible resolutions; in reality, Hardt says, the doctors kept life support on.

Nowhere does MED’s emphasis on diversity and humanity spice the curriculum more than in the final project of the clerkship. Outsiders expecting exam books or meticulously wrought case studies would be astounded at the actual projects that fourth year med students presented in November, from the aroma of jambalaya made by Toya George (MED’12) to a version of Jeopardy! with questions about international religions, emceed by Casper Reske-Nielsen (MED’12).

Jambalaya, plus the spirituals she plays on her computer for the class, reflect the comforts taken by people who share her southern heritage, George tells her classmates. Reske-Nielsen’s Jeopardy categories, flashed on the classroom screen, ranged from What’s in Store? (about the afterlife notions of various faith traditions) to Death’s a Drag. Classmates competed to answer clues like, “Famadihana is the practice of this with the dead to help the spirits join their ancestors.” (Answer: What is dancing? Famadihana is a tradition in Madagascar.)

The final projects’ nonscientific flavor, Hardt says, is a deliberate antidote to the emotionless professionalism that doctors typically adopt when confronting death and the bereaved: “‘Get tough, I’m sorry for your loss, suck it up.’ And we want to combat that and say, you know, these are people. And even though you have a specialized job, you’re still people too. You don’t have to block that out to become a good surgeon or good internist.”

It’s a lesson that stayed with Lucas Thornblade long after his visit to Swanigan’s home. “Learning about palliative care is the process of choosing which elements of medical care are appropriate for a person with a disease that may be terminal,” he says. And with the geriatrics clerkship, “for the first time, we’re caring for patients who may have more emotional and physical needs outside of the hospital than the patients that we’re used to caring for.”

Charles Swanigan died at home the evening after Thanksgiving with his family at his bedside.

This BU Today story was written by Rich Barlow. He can be reached at barlowr@bu.edu.