Historical Significance (LP) new

Historical Significance

“You show your humanity by how you see yourself not as apart from others but from your connection to others.” -Desmond Tutu

Equity and inequity are human creations. Following the 2020 murder of George Floyd, millions of people chose to demonstrate for a more equitable society, representing the largest protest movement in the history of the United States.1 People resolved to tackle the root causes of multiple and overlapping inequities in the United States and globally. Within healthcare, we have come to a growing awareness that structural change is necessary to tackle health disparities.2 Many dare to imagine what a truly equitable society would look like and how we might get there.

We can celebrate notable progress. In 2019, we marked the 50th anniversary of Pride Month and the Stonewall Uprising, and in 2020 we noted 30th anniversary of The Americans with Disabilities Act. In 2021, the federal government reaffirmed the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe’s recognition of their land in Massachusetts. At BUMC, we herald the ongoing efforts of faculty, staff, and students to make medicine more inclusive for all. The Racism in Medicine and Gender and Sexual Diversity Vertical Integration Groups have assessed our curriculum and made recommendations to address inequities in the curricular content. The Grayken Center for Addiction, the Boston Center for Refugee Health and Human Rights, and Boston Health Care for the Homeless programs continually advocate for individuals who are often deprioritized or forgotten in society. Members of our institution drive numerous additional efforts to address deep-rooted challenges in both medical education and beyond.

Despite progress made, much more remains to be done. In 2017, 8 percent of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and 29 percent of transgender people said they had been denied healthcare in the past year on account of their sexual orientation or gender identity.3 In 2021, 1 of out every 95 humans had fled their homes because of conflict and violence, becoming refugees, stateless, or displaced.4 Stigmatization of people with substance use disorders remains prevalent even as opioid overdose deaths in the U.S. increased to more than 100,000 in 2021.5

In addition to serving the communities around them, medical schools must face their internal challenges. The intellectual capital and societal influence accrued to academic medical centers – combined with the reality that social determinants of health drive 80-90 percent of the variation in health outcomes6 – places a special responsibility on medical schools to address health inequity. However, as of 2018 only 40 percent of medical schools had curricular content addressing racial inequity.7 Additionally, the numbers of Black, Latinx, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaskan Native medical students remain below their population levels in the United States,8 despite the fact that clinicians from diverse groups are more likely to understand the concerns of those groups and serve in diverse communities.9 While Black, Latinx, and Hispanic matriculants increased in 2021, American Indian and Alaskan Native matriculants declined by 8.5 percent.10

During medical school, students from historically excluded groups often endure marginalization. Black students may face lower academic expectations, microaggressions, and social isolation.11 Sadly, at least one study has shown that the more that first year African American students identified with their race, the more likely they were to experience depression and anxiety.12 In parallel, the 2013 AAMC student survey found that gender and sexually diverse medical students experienced decreased social support, elevated social isolation and stress, and a less welcoming overall environment in comparison to their straight classmates.13 Students with disabilities – apparent and nonapparent – often struggle to find clear and inclusive technical standards, receive meaningful access to accommodations, or obtain sufficient health and wellness support. 14,15

The struggle against inequity represents a moral duty. We live in an interconnected world, where the well-being of one group of people affects all of us. As medical educators, we join you in working to fashion a more just, inclusive, and peaceful world.

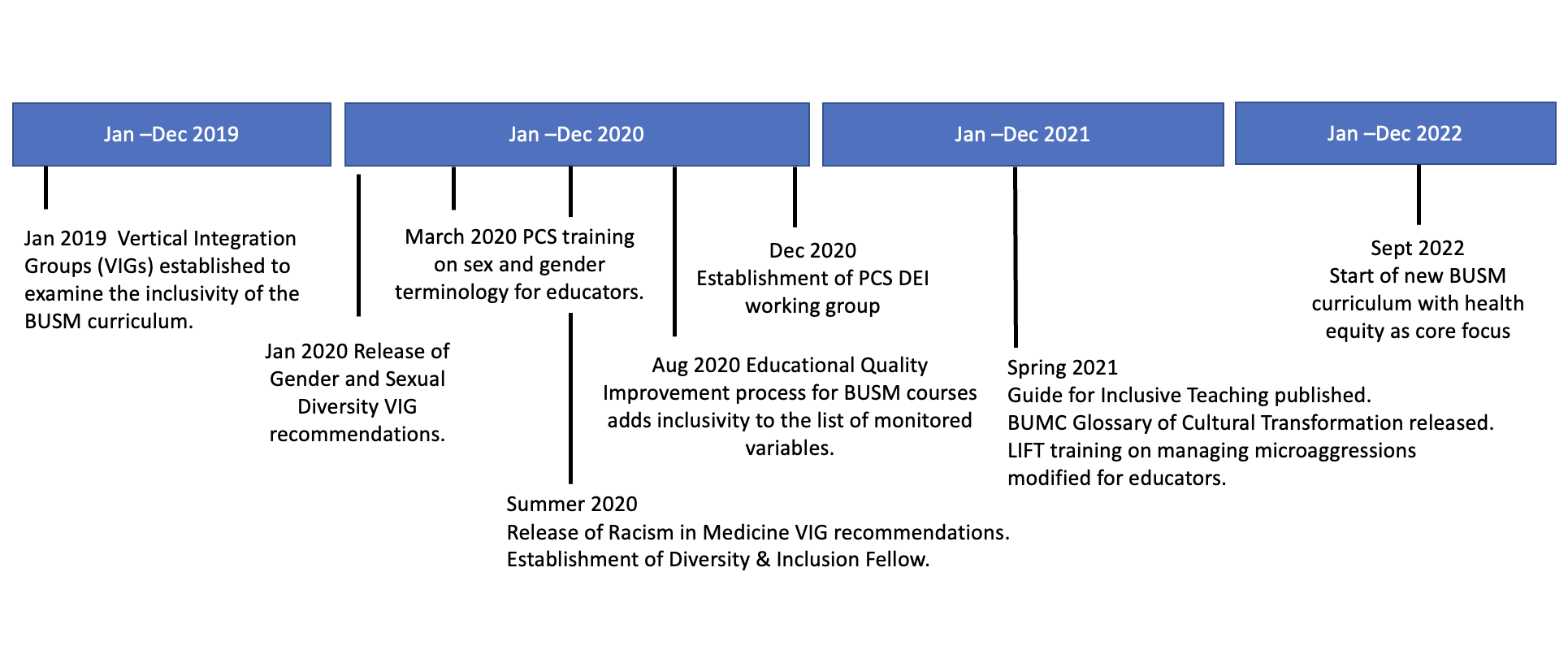

Snapshot of recent initiatives and progress in the ongoing work towards ensuring inclusivity in the BUSM curriculum.

Snapshot of recent initiatives and progress in the ongoing work towards ensuring inclusivity in the BUSM curriculum.

References

- Buchanan L, Bui Q, Patel JK. Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html. Published July 3, 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022.

- Lavizzo-Mourey RJ, Besser RE, Williams DR. Understanding and Mitigating Health Inequities — Past, Current, and Future Directions. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(18):1681-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2008628

- “You Don’t Want Second Best”: Anti-LGBT Discrimination in US Health Care. Human Rights Watch; 2018. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/07/23/you-dont-want-second-best/anti-lgbt-discrimination-us-health-care

- Refugees UNHC for. Figures at a Glance. UNHCR. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

- Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually. Published November 17, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm

- Magnan S. Social Determinants of Health 101 for Health Care: Five Plus Five. NAM Perspectives. Published online October 9, 2017. doi:10.31478/201710c

- Medical schools overhaul curricula to fight inequities. AAMC. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/medical-schools-overhaul-curricula-fight-inequities

- Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, Murillo AL, Grover A, Adashi EY. Diversity of the National Medical Student Body — Four Decades of Inequities. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(17):1661-1668. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr2028487

- Sanson-Fisher RW, Williams N, Outram S. Health inequities: the need for action by schools of medicine. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):389-394. doi:10.1080/01421590801948042

- Medical School Enrollment More Diverse in 2021. AAMC. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/medical-school-enrollment-more-diverse-2021

- Daher Y, Austin ET, Munter BT, Murphy L, Gray K. The history of medical education: a commentary on race. J Osteopath Med. 2021;121(2):163-170. doi:10.1515/jom-2020-0212

- Hardeman RR, Perry SP, Phelan SM, Przedworski JM, Burgess DJ, van Ryn M. Racial Identity and Mental Well-Being: The Experience of African American Medical Students, A Report from the Medical Student CHANGE Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(2):250-258. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0136-5

- Hollenbach A, Eckstrand K, Dreger A. Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender Nonconforming, or Born with DSD: A Resource for Medical Educators.; 2014.

- The disabilities we don’t see. AAMC. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/disabilities-we-dont-see

- Meeks L, Jain N. Accessibility, inclusion, and action in medical education: Lived experiences of learners and physicians with disabilities. AAMC. Published online 2018. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/249/