LGBTQIA+ Cancer Patients

Filimonov AK, Rivera E, Flynn D, Goldina A, Denis G, Wisco JJ. Identifying and Revealing Gaps in Healthcare Access Amongst Pelvic Cancer Patients Who Identify As LGBTQIA+. 2023; in preparation.

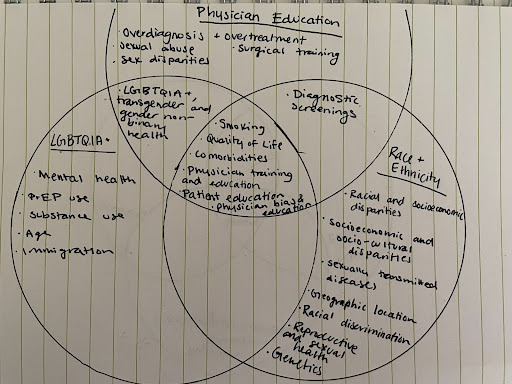

Code book of papers analyzed using grounded theory thematic meta-analysis (GTTMA). Each theme is broken down into sub-themes and followed by the second level of representative open codes from the analysis.

Physician Education:

“Trust is an essential component of effective CBPR partnerships. Building trust is less about formal meetings and procedures and more about consistently “showing up” for the community. “Showing up” does not just entail attendance at planned project meetings but support of community activities. For example, in working with American Indian and Alaska Native communities, one might attend social (e.g., Pow Wows, community dinners, talking circles) or health-related activities (e.g., walkathons and fundraisers supporting Native health initiatives). In working with homeless communities, one might serve meals at drop-in centers, participate in community-based agency fundraisers, or help organize volunteer activities at shelters. The key to building strong relationships in CBPR is showing authentic and consistent support for communities on their terms.”

“Recent studies suggest physicians’ prejudices substantially influence their feelings about patients and their treatment decisions. As a result, such prejudices appear to be major contributing factors to healthcare disparities… The greatest burden of these efforts lies with healthcare providers, academia, community organizations, payers, and government, with efforts to eliminate both access-related differences and the healthcare consequences of personally mediated and institutionalized biases.”

“Providers must, both individually and through their professional organizations, explore self-awareness, recognize stereotyping, develop skills for cross-cultural communications, and learn to explore patients’ views of pain, sickness, and treatment… Patient-based factors can be addressed by improvements in patient education programs aimed at increasing patient knowledge on how to access care, actively participate in medical decision making, and follow through on medical treatment plans. Providers, hospitals, payors and regulators will contribute to the elimination of healthcare disparities through improvements in both cultural “sensitivity”—the capacity to recognize that differences exist and the willingness to adapt behaviors—and cultural “competency”—the tools necessary to carry out plans, policies and practices to respond to such differences. Ideally, cultural “proficiency” in healthcare will achieve the same attention that knowledge and technical proficiency have in our quest for quality, affordable, accessible and equitable care.”

“One factor that may affect choices around transition is access to care, as not all patients have adequate access. The consequences of insufficient access to therapies may have profound effects, with remarkably high rates of depression and suicidality reported in this population, with some patients resorting to taking street hormones with no medical monitoring… The extent to which one may undergo hormonal or surgical intervention is highly reliant on not only personal preferences, but also health care barriers. In fact, almost 25% of individuals identifying as transgender in one survey reported not having access to medical care for transition. This includes the failure of most insurance providers to cover hormonal therapy, gender transition surgery, mental health services, as well as inadequate infrastructure for clinicians to code these therapies properly for reimbursement.”

“Timely and on-going access and uptake of sexual health screenings among YMSM, particularly Black YMSM, is critical as these groups are disproportionately affected by HIV, and high rates of undiagnosed or untreated STIs may contribute to HIV disparities in this population… Additionally, while there are no established screening guidelines for MSM, yearly pap screenings for anal cancer may be undertaken.”

“Patient barriers that have been the primary focus of research on clinical trials participation for underrepresented populations include lack of insurance coverage, high out-of-pocket expenses, fear, suspicion, concerns regarding negative side effects and invasive procedures, and lack of awareness about health research studies. However, low research literacy, or limited understanding of research processes, may also be a key contributor. Limited research literacy and unfamiliarity with research concepts may also result in individuals consenting to participate without comprehending the full procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives of participating in research.”

“Increasing clinical trial and biobanking participation among underrepresented populations is a pressing need. A standardized research communication tool is poised to address communication challenges in the recruitment process by facilitating conversations between researchers and potential study participants.”

“Complicating the issue of pain management is the subjective nature of pain assessment, both as expressed by the patient and as interpreted by the physician. Beyond obvious communication barriers caused by language differences, the patient may provide nonverbal cues that are misleading to the physician. Further, in a “no pain, no gain” culture, particularly one in which patients have a lack of trust or even a fear of the system, they may be reluctant to imply that they either have significant pain or cannot “handle it” themselves. Depending on socioeconomic and insurance status, patients may be treated for chronic pain at an emergency center and only when they experience an acute exacerbation. They may seek physician care reluctantly and only after seeking relief using their traditional culture-centered pain remedies and/or “healers.” Many times these alternative treatments can confound the treatment and the diagnosis of pain.”

“Physicians’ treatment decisions may be confounded by an inability to obtain needed information from the patient, as well as by perceptual biases (eg, viewing men as “stoic” and women as “hysterical”). Physicians may experience a level of discomfort with patients of a dissimilar culture; they may tend to stereotype patients based on culture and/or ethnicity as alcohol or drug abusers, or as physical abusers (men) or physically abused (women). Cultural, ethnic, and gender differences should be noted by physicians. They should strive to develop and implement in their practices culturally, ethnically, and gender-sensitive intervention models that have applicability to the management of pain as well as other morbidities… Accuracy of diagnosis is also of great importance, for it helps in quantifying the projected time of disability and the specifics of activity restrictions. Imaging studies tend to be done earlier in an attempt to obtain a more specific diagnosis. Physical therapy is often used to get the patient off of restrictions more quickly. Subspecialty referrals are more common in this area of medicine both for diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment issues. Time and accuracy are essential in these cases.”

“All participants reported sexual problems and half of the women reported sexual distress since treatment. Almost all women reported pain during sexual contact. The majority reported symptoms of a shortened and/or tightened vagina, vaginal adhesions, loss of sexual desire, lubrication problems, a burning sensation and sensitive vaginal skin, loss of blood after penetration, reduced sexual enjoyment, and/or fear for sexuality (e.g., because of possible pain or infections). Also, one-third reported loss of sexual satisfaction… Participants’ risk perception was influenced by the way they perceived the instructions from their health care providers. The two women who never intended to perform dilator use reported insufficient information provision. One of them received some information, but no dilator set or instructions. She thought her doctor estimated it was not necessary… More than half of the women expressed negative emotions about dilator use. Experiencing pain, blood loss, or discharge during dilator use made half of the women anxious to use a dilator, and a few were bothered by tension of the pelvic floor muscles. Some had stopped dilator use because of it… A couple of women were frustrated about their health insurance company not paying for the dilator set (as one of the two hospitals itself did not supply them) or having to buy neutral (water- or silicone-based) lubricants themselves. One older woman stated being embarrassed by having to explain at her local drugstore why she would need lubricants… However, some women stated to lack professional advice or support and therefore did not use a dilator more often. Another woman regretted not getting more follow-up appointments with her helpful oncology nurse. Several women suggested that it would be helpful to have at least one consult with a psychologist or other health care provider to support them with dilator use at the end or just after treatment.”

“We completed 4 focus groups, with a total of 23 female surgeons. This included 2 trainee focus groups with 15 participants and 2 attending focus groups with 8 participants. General, colorectal, vascular, neurosurgery, urology, OB/GYN, urogynecology, gynecologic oncology, and orthopedic surgery were represented. No additional or differing themes were identified in the attending groups, with these groups reporting that the same negative experiences continue after the completion of training. Four overarching thematic categories emerged from the focus groups: exclusion, increased effort, adaptation, and resilience to workplace slights… The advice of mentors heavily influenced participants’ career choices; thus, negative comments during critical times when trainees choose a career direction were mentioned as something that may push women away from surgery. One trainee noted, “He told us that the ladies in the room might want to think about something like [pediatrics] or family medicine, so that we can be at home and see our children grow up.” If a trainee was determined to pursue a surgical specialty, they would often be encouraged to “choose a lifestyle-comfortable surgical specialty,” such as breast surgery or OB/GYN… These findings support prior work indicating that gender bias is pervasive in surgical specialties. We identified exclusion, increased effort, adaptation, and resilience to workplace slights as common themes for female surgeons’ experience of gender bias. Trainees in our study had significantly worse experiences than attending surgeons for 3 Sexist MESS domains, but gender bias and microaggressions were cited as a problem for the majority of female surgeons.”

“A further barrier to the conceptualization and implementation of a broad scale manpower design is the unwillingness of a large percentage of medical and health professionals to accept the potential roles of new professionals, as well as to come fully to grips with the concept of ‘consumer participation’ – from policy formation to service delivery. Both concepts demand a re-examination of the traditional medical hierarchy and roles… The greatest single obstacle to creative new systems of healthcare lies in the unfortunate training of most professionals that locks them into a “role.” If doctors, nurses and other health workers can conceive of their “role” as a series of tasks, some of which can more appropriately be performed by new professionals, movement toward more creative and efficient systems will result… Rather than engendering an atmosphere of distrust and threat a spirit of cooperation and mutual respect can be fostered.”

“In recent years, some hospital institutions have insisted that every history and physical examination on a patient admitted to hospital include a rectal examination, but a recent study from a teaching centre in Pittsburg revealed that 56% of all admissions did not document a digital rectal examination… Over 80% of patients admitted to the medical clinical teaching unit in a university hospital had no documentation of performance of a rectal examination by the medical resident physician or the attending staff directing the care of the patient, while breast and pelvic examinations appeared to be even more rarely done.”

“This study also demonstrated that rectal examinations documented by medical residents appear to be largely focused on the detection of blood loss rather than a true ‘physical examination’ of the rectum, anus or prostate gland. Moreover, the absence of rectal examinations by attending staff physicians indicates that the results of these rectal examinations done by medical residents were not confirmed by attending staff physicians, even in patients who were admitted with a primary gastrointestinal disorder… Similarly, there was a failure to document a clinical evaluation of the prostate gland in 44 of 45 males in this study, including 26 patients over the age of 60 years.”

“Compared with male physicians, female physicians performed rectal examinations on males about 50% less than did male physicians. This difference was even more dramatic for female patients. Female physicians performed rectal examinations in about 45% of the female patients, whereas male physicians performed rectal examinations in less than 5% of the female patients admitted. Breast and pelvic examinations were even more rarely documented (this lack of documentation was equal in male and female resident physicians).The reasons for these apparent ‘sex-based’ differences in examination rates require further elucidation… Instead, it appears that female patients are most likely to be incompletely examined in a teaching hospital setting if initially seen on a medical ward by a male resident physician. Because there are apparently increasing numbers of complaints, particularly toward male physicians with respect to sexual harassment, a fear of potential consequences, including litigation, may have been partially responsible for the results observed. If so, a greater documentation of nursing staff presence would be expected, but this did not occur. Alternatively, some physicians, anticipating that a subsequent referral to a gastrointestinal subspecialist or a surgeon will result, may feel that an additional examination may be superfluous. If so, patients not referred for subspecialty consultation with a gastrointestinal disorder would be expected to have had a rectal examination. This did not occur.”

“The term “lesbian” describes “not only sexual orientation, but also an identity based on psychological responses, cultural values, societal expectations, and a woman’s own choices in identity formation. Bisexual women have the potential for attraction to both men and women; they are attracted to individuals rather than to a person of a particular gender or biologic sex. Lesbians are diverse and represent all religious, ethnic, economic, age, and cultural groups. Because same-sex behavior is stigmatized and lesbians often defy stereotypes, they may remain a hidden population in their interactions with researchers and healthcare providers. The assumption of heterosexuality is so prevalent that healthcare providers and researchers may perpetuate the invisibility of lesbians within the healthcare system. Not only are lesbians often invisible within the healthcare system, they also are less likely than heterosexual women to use preventive cancer-related screening services.”

“ENCOREplus®, a national program from the YWCA designed to reach underserved women from all ethnicities, was tested in 27,494 women. The program activities included outreach, education, enabling, support services, and provider networking and linkage. Of the participants older than 40 who were nonadherent to breast cancer screening guidelines at baseline (70%), 58% received mammograms in the six months following the intervention. Of the participants older than 18 who were nonadherent to cervical cancer screening guidelines at baseline (69%), 37% received Pap tests in the six months following the intervention. Another program designed to serve women from all ethnicities used formal and informal meetings to disperse written materials, show videos, and generally educate women, all in their native language, about breast and cervical cancer and associated screening guidelines… All the interventions were better than no intervention. The reminder postcard was the best, increasing adherence by 25%. In the second study, 249 patients aged 50–75 in central North Carolina who had not had any colorectal screening tests in five years and did not have a family history of colorectal cancers were randomized into two groups. The first group watched an 11-minute video about colorectal cancer, received an educational brochure about colon cancer screening, and had their charts flagged indicating interest in screening. The other group watched a video about car safety, and their charts were not distinguished. Screening tests were completed by 37% of the intervention group and 23% of the control group (p < 0.03).”

“After the intervention, one woman, whose sister had ovarian cancer, obtained a pelvic examination. Prior to the intervention, she “just could not make [herself] do it.” Of the 22 women, 12 (55%) were up-to-date with their colorectal cancer screening, having had a recent sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Of those 12 women, two stated that they would never have another because of the pain associated with the procedure… The women described three major barriers to screening: (a) lack of money, (b) fear of the pain, and (c) their healthcare provider did not arrange for the test.”

“About one-half of men preferred the self- or partner anal exam rather than a doctor-performed exam which may speak to embarrassment associated with DARE and stigma regarding the anus; thus, SAE/PAEs may increase anal cancer screening access by providing an option to detect an abnormality that motivates a clinic visit.”

“The symptoms were grouped as National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK guidance – positive (abdominal or pelvic pain, increased abdominal size or bloating, loss of appetite/feeling full and increased urinary urgency or frequency) or modified Goff Symptom index positive (abdominal or pelvic pain, increased abdominal size or bloating and loss of appetite/feeling full). The Goff symptom index includes duration and frequency of symptoms… The date the woman was first seen in hospital, the speciality involved and the route to that appointment was recorded. For those residents in England, this was supplemented where missing, with HES data. The routes were classified as 1) emergency presentation (via accident and emergency department) 2) two-week urgent ‘cancer’ referral to rapid access outpatient diagnostic clinic 3) routine referral to secondary care (e.g. gynaecology or colorectal outpatient clinic). The patients who were seen privately (outside the NHS) were included in this group.”

“Men who received care in public clinics, hospitals, or VA sites were more likely to have undergone general screening, and further, rectal screening. Notably, adolescents who seek sexual health care through a primary care physician may also receive less comprehensive sexual health care. Men experiencing STI symptoms may also be more likely to seek care at a clinic (e.g., public health STD clinics). Clinics also may reduce or eliminate a number of barriers to accessing care, including concerns about billing or parental notification. High rates of uninsurance among young men and MSM may also steer men to clinics. Further, clinics may offer specialty sites where services are tailored to gay, bisexual, or LGBT clients and where routine check-ups are the norm.”

“Surveys show that up to 70% of health care providers report unfamiliarity with screening recommendations for transgender individuals, which is, in part, due to lack of health maintenance guidelines specific to transgender patients. Moreover, this may lead to low-quality care and poor recommendations… Our study also highlights areas in which physicians provided erroneous recommendations to transgender and gender diverse patients. In two cases, providers documented counseling transmasculine patients that testosterone therapy alone provides adequate contraception, although previous reports have proved this to be false. In parallel, our cohort AFAB showed significantly lower cervical cancer screening rates, which may be due to a misconception among providers and patients that transgender men not engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse do not require regular screening.”

“The women who delay care were also more likely to have been on weight-loss programs five or more times. Many health care providers reported that they had little specific education concerning care of obese women, found that examining and providing care for large patients was more difficult than for other patients, and were not satisfied with the resources and referrals available to provide care for them… Concerning provider attitudes: many large women perceive that they are treated less respectfully than thinner women; they think that they are not getting appropriate care because of their weight, and they are concerned that providers lack training and experience to perform adequate pelvic exams. In issues concerning weight: women were embarrassed or angry at routine weighing; women viewed unsolicited weight-loss advice as intrusive and distracting from the real concerns of the women’s medical visit. In issues concerning medical equipment: regularly used medical equipment was not routinely available in a size that was functional for large women, such as blood pressure cuffs, speculums, and examination tables. The combination of some or all of these barriers negatively affected women, but affected a much higher percentage of larger women. The result was delay, reluctance, or avoidance of medical visits.”

“After being taught how to perform an SAE or PAE, 93.0% of men said they planned to do another in the future. After completing the exam, five men said they were not willing to do the SAE/PAE again due to lack of concern about anal cancer, dislike of the exam, forgetting how to do the exam, embarrassment, dislike of potentially toughing faeces, and/or difficulty reaching the anus. Most men (92.5%) reported they would see a doctor if they detected an anus abnormality after doing an SAE/PAE. Similar proportions of men preferred the SAE/PAE exam and a doctor examination. At the end of the clinic visit the clinician asked the men “if the procedure hurt” without reference to any particular procedure during the visit, e.g., DARE or SAE/PAE. No men reported bleeding although 15.0% reported that a procedure hurt. During the study, this question was expanded so that the final 54 participants were asked more detailed questions about pain. A total of 4/54 (7.4%) of these men reported any SAE/PAE pain with an average score for these four men of 1.75 on a scale of 0–5 where 0 indicates no pain. All four said the pain would not make them avoid the procedure in the future… Since lack of knowledge about anal cancer is associated with substantial anxiety after an abnormal screening result, increased anal cancer educational efforts are needed for MSM in addition to education about self-palpation if subsequent studies confirm a high proportion of MSM already self-palpate for disease.”

“Pap screening programs have been difficult to implement in low-resource settings because of limited infrastructure and access to trained cytopathologists and clinicians. Consequently, a region with low screening coverage such as Eastern Africa still has among the highest estimated annual incidence of invasive cervical cancer in the world (34/100,000). A primary screening approach based on testing for the central etiological risk factor for cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, in self-collected specimens could help increase access to screening in low-resource settings… In terms of public health implications, our results of AHPV self-testing versus physician testing performance were from a high-risk population in a low-resource setting and thus not necessarily generalizable to low-risk populations. Also, one concern of self-collection in primary screening is that a woman who tested HPV positive may not return for follow-up screening or treatment.”

“Effective communication and information provision in health care is considered a pre-requisite for informed decision-making and represent important contributors to patient satisfaction and coping… Clearly written patient education materials play an important part in supplementing verbal discussions with health care professionals. There is a growing interest in how information and communication interplay with patient decision-making and subsequent clinical outcomes.”

“Content analysis of the patient education materials identified similar inconsistencies in recommended practice. While explanation and rationale for the use of dilators was present in 91% (n = 29) of the information leaflets, few of the leaflets (31%) offered information on the aetiology of sexual health difficulties within the context of wider pelvic radiotherapy side effects… It was interesting to note that although medical staff were not usually involved in the delivery of patient education, with regards to vaginal dilation, 48% of respondents indicated doctors played a role in evaluating patient compliance… Despite this evidence, surveys consistently report that certain areas of patient education and information are poorly conducted or missing from health care provision… This study has highlighted persistent inconsistencies in patient education regarding vaginal dilation within current UK practice and identified the lack of psychosexual content in both written materials and clinical discussions.”

“Despite the significant effect on sexual function, clinical assessment of treatment-induced SD following RT is an underexposed item during regular radiation oncologist consultations. For this reason, patients should be actively informed on problems associated with radiation-induced SD and must be guided toward appropriate therapeutic options. To our knowledge, information concerning the attitude of radiation oncologists is barely available yet… As medical doctors are the major information source of treatment-induced morbidity and have a legal obligation to inform their patients on treatment-induced morbidity, investigating their current sexual counseling practices is of significant importance.”

“The respondents were given a list of possible barriers for discussing SF, in order for them to indicate to which extent they agreed. Radiation oncologists mentioned “patient is too ill” to discuss sexual issues as a major barrier (36.2%). The second barrier, to which 32.4% agreed, was “no angle or reason for asking.” Other barriers were “advanced age of the patient” (27%), “culture/religion” (26.1%), “language/ethnicity” (24.5%), “sexuality is not a patient’s concern” (23.9%), “patient doesn’t bring up the subject” (20%), “lack of training” (19.3%), and “patient is not ready to discuss sexual functioning” (13.1%). The barriers that did not keep radiation oncologists from sexual counseling were all barriers regarding gender, “it’s someone else’s task” (2.6%), “age difference between you and the patient” (3.5%), “afraid to offend the patient”(3.5%), and embarrassment (5.3%)… In order to provide this component of care, radiation oncologists need to have good communication skills, an open and nonjudgmental approach, and knowledge of the potential consequences of radiation therapy on sexuality. Especially for gastrointestinal patients who possibly receive radiation on or close to the pelvic area, awareness should be improved among radiation oncologists. Both standard education within radiation oncology residency as additional education for practicing radiation oncologists are strongly recommended. Radiation oncologists who have the intention to integrate sexual health in their practice and would like to make use of a structured framework, could for example counsel with the widely used Permission (P), limited information (LI), specific suggestions (SS), and intensive therapy (IT) (PLISSIT) model. Guidelines and standard operating procedures for radiation treatment should implement possible sexual side effects and the importance of addressing them as a part of informed consent and follow-up.”

“Individuals with higher educational levels had increased odds of contact with specialist care compared with those with low educational level (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.17–2.95) when adjusted for age… A high educational level was significantly associated with increased odds of having contact with specialist care. There may be several explanations for this. Higher education could imply better health literacy and a better ability to communicate with the GP, and the GP may then be more likely to refer the patient to a specialist… Furthermore, high educational level is associated with an increased likelihood of keeping appointments, which might partly explain our findings. We found no significant associations with other sociodemographic variables that have been linked to prolonged time to diagnosis in other studies. This may suggest that health literacy is the strongest determinant for contact with a specialist, and that possible associations with income and labour market affiliation may be due to confounding.”

“Among individuals reporting at least one of the four cancer alarm symptoms, no significant association with GP contact was found for BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, household income, educational level or marital status. Thus, the variables included in the adjusted logistic model were age group, labour market affiliation and ethnicity… Likewise, immigrants had higher odds of reporting GP contact (OR 1.56, 95%CI 1.13 to 2.15) compared with ethnic Danish individuals… Women in the oldest age group and immigrants had significantly higher odds of having contacted the GP when reporting at least one of the four symptoms. No associations were found with smoking status, BMI, alcohol consumption, labour market affiliation, household income, marital status or educational level… This study found that higher educational level was positively associated with increased healthcare seeking, while no significant associations were found for lifestyle factors. This might indicate that educational level is a proxy for health literacy, and that the latter is the determining factor for healthcare-related actions rather than lifestyle.”

“Members of the LGBTQ+ community at large have historically experienced high levels of discrimination and violence, as well as greater rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide… Patients from the transgender community appear to have higher rates of cancer-related risk factors. Members of this community, as well as other sexual and gender minority groups who have experienced violence or discrimination, have reported higher rates of cigarette/tobacco use and alcohol use including binge drinking. These lifestyle factors are important to consider in transgender men, as cigarette/tobacco use has been associated with cervical neoplasia, vulvar neoplasia, and mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer.”

“One survey of gynecologists reported that 80% of providers had not received any training on caring for patients who are part of the transgender community. When considering provider confidence in caring for transgender male patients, less than 30% of gynecologists felt comfortable with this role. Most of these providers reported being unaware of recommendations for cancer screening in this patient population… Furthermore, providers should receive education on these topics so they can become familiar with the use of hormones and surgical interventions for gender transition to facilitate better care for transgender patients and recommend or collaborate with providers with higher level of expertise… Gynecologic oncology provokes emotional distress for many patients. Treatment may include aggressive surgery and intensive medical interventions with high recurrence rates among patients with ovarian cancer and other advanced malignancies. Additionally, there is potential genital physical disfigurement due to necessary surgical or radiation treatment among patients with some gynecologic malignancies, leading to alterations in physical appearance and sexual experiences, and this may add to the stress of seeking and undergoing care in this area among transgender men.”

“A key feature of interactions that went poorly was a provider who either lacked knowledge of the health care needs of TGGNB individuals or lacked experience treating TGGNB patients…A common experience described within this theme was the denial of care related to patients’ TGGNB identity. Participants described three distinct ways in which they experienced denial of care. First, participants reported denial of care related to transition. For example, one participant described a provider who refused to discuss hormone replacement therapy “due to religious beliefs” (Genderqueer person, 30 years old). Denial of care was also experienced because of the participant’s gender identity.”

“Concerning education, participants wanted health care providers to have what one participant referred to as “trans 101,”—essential, basic information about gender identity, sex, and the major health concerns faced by TGGNB. Other participants echoed this, saying providers “should know the basics regarding our unique circumstances and health needs. They should understand hormone therapy and how we see our bodies” (Genderqueer person, 34 years old). Further, participants felt that medical students should not just receive education and training on TGGNB health care, but that the training specifically should involve TGGNB people themselves. Simply stated, provider training on trans health and patient care should involve consulting with “actual trans people” (Transgender woman, 28 years old)… Participants also noted they should not be responsible for educating providers, and that it is providers’ responsibility to seek education on… In addition to training providers in gender‑ affirming care, our findings suggest the necessity of implementing institutional and system‑ level changes to support providers in their abilities to provide such care to TGGNB patients.”

“In general, there is a dearth of published research examining LGBT youth and the health care system. Youth may not disclose sexual risk to providers, and providers may be uncomfortable or untrained in addressing sexual behavior, sexual minorities, or sexual minority youth. Low rates of rectal screening in this sample may be attributable to patient factors (e.g., not disclosing sexual behavior to providers, or unawareness of the need for screening), or provider factors (e.g., discomfort with sexuality, sexual minority youth, or anal health)… Provider LGBT cultural competence is especially important, as homophobia, racism, and lack of culturally competent health care may prevent MSM from accessing care, and may taint future health care interactions.”

“We found significantly lower rates of contraception use and cervical cancer screening in our population compared to national rates and no significant difference in utilization based on health insurance type… Our population is unique, as 92% were insured and <3% were uninsured, suggesting that no matter how robust the insurance coverage, transgender and gender diverse individuals still face health inequities. For example, Table 5 shows a general trend toward lower utilization rates in our rural cohort compared to urban settings. Transgender individuals living in rural areas often experience increased stigmatization by health care providers, leading to avoidance of seeking health care services due to fear of discrimination.”

“In patients with anastomotic leak, mortality rate increased up to 16% vs 2.0% in patients without anastomotic leak (P < .0001). At multivariate analysis, rectal location of tumor, male sex, bowel obstruction preoperatively, tobacco use, diabetes, perioperative transfusion, and the individual surgeon were independent risk factors for anastomotic leak. The surgeon was the most important factor (mean odds ratio 4.9; range 1.0 to 13.5)… The individual surgeon is an independent risk factor for leakage in double-stapled, colorectal, end-to-end anastomosis after oncologic left-sided colorectal resection.”

“A shorter learning curve than standard LRP has been reported in addition to approximately an hour less operative time and half the estimated blood loss. However, these advantages, if real, come at a great financial cost. An important concern for both these laparoscopic approaches is that the surgeon’s skill and prior results with open prostatectomy likely greatly influence if or when he considers LRP or RALP to be an improved technique over open prostatectomy. It may take hundreds of cases for a truly expert open radical prostatectomist to achieve similar results and comfort laparoscopically, emphasizing the importance of critically evaluating the training and learning curves of these procedures. The highest volume standard laparoscopic prostatectomy surgeons and centers, performing 6 to 9 cases per month (100–200 cases within 1 to 2 years) developed and pioneered this operation and demonstrated its increased operative time, complication rates, and positive surgical margins during the first 50 to 60 cases, thus defining the LRP learning curve… We observed an increased complication and positive surgical margin rate than in prior lower volume series. It is unclear if this is related to surgeon skill, surgical approach, or a stricter definition of complications and positive margins.”

“The common theme from these reports is that the number of RPs previously performed by a surgeon affects patient outcomes, with as many as 200 RPs postulated to be required before a surgeon reaches the expert portion of the learning curve… Here we have reported that patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing RP performed by 2 surgeons recently graduated from a urologic oncology fellowship training program had outcomes similar to those of patients treated by more experienced surgeons… Our study serves as a baseline for assessing the impact of a fellowship-type training on the morbidity of open RP. We suggest that being trained in a clinically rich environment, where an experienced surgeon and trainee perform the procedure together, might be one way to accelerate the learning process associated with RP… Much of the average surgeon’s experience is acquired during residency training. The breadth of procedures required to complete a urology residency program nowadays is staggering; urology residents are trained in endourology, incontinence and reconstruction surgery, transplantation surgery, impotence and infertility surgery, pediatric urology, and urologic oncology.”

“Primarily, urologists need to recognize that smoking cessation counseling can and should be an element of their care for bladder cancer… Some might argue that once a man is diagnosed with bladder cancer, it is already too late to quit smoking. In the United States for instance, bladder cancer is generally a disease of the elderly, with more than 70% of cases diagnosed after the age of 65 years. Moreover, among men, the median age of diagnosis is 72 years. Large cohort studies and meta-analyses, however, have shown that benefits from smoking cessation can exist even among the elderly… The first step in preventing bladder cancer is to educate men and the public about the risks of smoking, as currently, it appears that knowledge is lacking.”

“The presence of obesity is correlated with sexual and erectile dysfunction. In women, this correlation links obesity to disorders of the female cycle and hormone regulation, which are in turn associated with sexual function. Poor self-acceptance of body image, comorbid mental disorders, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships may aggravate the situation… Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) is a collective term for a broad spectrum of clinical conditions. They mainly include urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction. The prevalence increases with age, and it is estimated to be between 2% and 42% in adult females. Obesity is known as an important risk factor for developing pelvic floor disorders. The greater intra-abdominal pressure, weakened pelvic floor muscles, and structural damage or neurologic dysfunction contributing to prolapse and incontinence are possible mechanisms for the effects of obesity on PFDs.”

“Overweight and obesity are associated with an increased risk of a number of cancer diseases. Among women, sex-specific cancer represents a large proportion of malignant diseases: breast cancer is the most common and cervical cancer is the sixth most common cancer entity globally. Decreased estrogen levels have been supposed to increase the risk of developing breast and endometrial cancer and are therefore among the reasons for the increased incidence of malignant diseases in women. Endometrial hyperplasia is a precancerous condition that arises in the presence of chronic exposure to estrogen unopposed by progesterone, such as in PCOS and obesity. Therefore, regarding sex-specific aspects in the bariatric treatment of women, the question of the influence of surgery-induced weight loss on sex-specific cancer arises. A histologic study of the endometria of morbidly obese women who presented for bariatric surgery found a prevalence of endometrial hyperplasia of about 10%. Bariatric surgery not only changed the risk variables for the development of endometrial cancer but also improved the quality of physical health significantly. Therefore, it can be assumed that severely obese women represent a risk group in terms of endometrial cancer.”

“The three most agreed reasons that keep GPs from asking about SA were ‘no angle or motive for asking’ (81.6%), ‘presence of third parties’ (73.0%), and ‘not enough training’ (54.4%). Responders younger than 47 years old agreed more often with ‘presence of third parties’ and ‘afraid to offend the patient’ (linear-by-linear association, P <0.001, P = 0.025). Responders older than 46 years agreed more often with: ‘sex is a private matter’ (linear-by-linear association, P = 0.001). GPs with 10 years of experience or less agreed more often to the barrier ‘presence of third parties’ (P = <0.001)… Only 0.4–1.1% patients told their gynaecologist spontaneously about abuse during a visit to the clinic. Incomplete knowledge together with little disclosure from patients might lead to an underestimation and restricted discussion of SA by GPs… the participating GPs were motivated to enhance their knowledge on how to counsel for SA.”

“In most practices (84.3%), the NP is assigned to perform the cervical smears. Female GPs performed the cervical smear significantly more often than their male colleagues did (P = 0.030). The responders estimated that 34.5% of their NPs never asked, 21.3% rarely asked, and 12.9% sometimes asked about SA before performing the cervical smear. Three per cent of the NPs are estimated to ask always, often or regularly in advance of a cervical smear and 28.1% of the responders did not know if their NPs asked about SA (n = 310)… Most of the cervical smears are performed by NPS; half of them were trained during a course instructing them how to perform the procedure. According to the GPs’ estimation, one-third of the NPs never ask about negative sexual experiences in advance of a cervical smear. Approximately one-third of the GPs did not know if their assistant asks about SA in advance of a cervical smear.”

“Women were significantly more likely to have an ICD-9 claim for microscopic hematuria (p<0.001) and less likely to have an ICD-9 claim for gross hematuria… The reasons for delay are likely multifactorial. Johnson and colleagues found in a claims-based study that only 47% of 559 men and 28% of 367 women presenting with hematuria were referred for urologic evaluation… In addition to referral patterns, patient beliefs and compliance as well as access to care may also play a significant role in delayed diagnosis but have received limited study.”

“On univariant analysis when grouped by systems, women with gastrointestinal symptoms had worst survival and those with gynaecological and urinary symptoms the best. Compared to those presenting via two-week urgent cancer referral, women presenting as an emergency had significantly worse survival. Irrespective of route to diagnosis, compared to women initially managed by a gynaecologist, those initially managed by the emergency physicians or gastrointestinal physicians/surgeons had worse survival… Our findings that emergency presentation confers worse survival compared with two-week urgent ‘cancer’ referral are in line with Barclay et al. and Altman et al. It highlights the need to ensure for fast tracking of referrals to gynaecological services… Women with these symptom complexes are likely to have advanced disease and poorer survival. The lack of significant impact on survival of healthcare interventions such as route or interval to diagnosis or secondary care team involved in initial management suggests that in invasive epithelial tubo-ovarian cancer, tumour biology is the overriding driver of survival.”

“It should be clear to urologists that they can make a significant difference by helping men to quit smoking. As reported in the male British Doctor׳s Study, quitting smoking at 40 years of age can add 9 years of life expectancy to a man… Smoking cessation is just a piece in the men׳s health puzzle. By adopting a holistic men׳s health lens, urologists can find new opportunities to make a positive effect on the health of men. A useful tool is the American Urological Association׳s Men׳s Health Checklist, which provides a guide for physicians in coordinating the care of male patients… Men׳s attitudes toward smoking and bladder cancer will not change on their own. By connecting the dots through awareness, education, research, and healthcare delivery, urologists can make a difference. The benefits of smoking cessation for men are indisputable, and efforts should be made to incorporate it into regular care.”

“Overuse encompasses overdiagnosis, which occurs when “individuals are diagnosed with conditions that will never cause symptoms,” and overtreatment, which is treatment targeting overdiagnosed disease or from which there is minimal or no benefit… Be cautious in using diagnostic tests to identify disease without high pretest probability because most disease can be diagnosed with a thoughtful history and skillful physical examination. Clinicians managing patient symptoms without obvious cause should be aware that physical and psychological symptoms co-occur, should recognize that most symptoms resolve within a few weeks to months, and should consider that serious causes of symptoms rarely emerge during long-term follow-up.”

LGBTQIA+:

“Our study also highlights the continued mental health crisis in the transgender population. Consistent with other studies, 36% of our sample had contemplated suicide and 10% made an attempt in the past year, compared to 4 and 1%, respectively, in the general Colorado population. Providers should ensure to screen for and address mental health issues for all transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Public health programming should include interventions specifically targeting this population. We found that access to a transgender-inclusive provider may partially mitigate these mental health disparities, as it is associated with lower rates of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. The most prominent factors associated with a perception of being transgender-inclusive were knowledge about transgender health, addressing transgender-specific health needs, and being comfortable with transgender patients. This aligns with other studies that have found that increased support, provider knowledge about transgender issues, and access to transition-related care improve mental health.”

“An elevated risk among sexual minorities might have only a small effect on all-cause mortality. Consistent with that perspective, we observed a much elevated hazard for suicide-related mortality among WSW compared with women reporting only male sexual partners despite the lack of differences in all-cause mortality. Furthermore, the robustness of the elevated rate is consistent with previously reported odds of suicide attempts among sexual-minority adolescent and adult females compared with heterosexual females. These findings suggest that the greater vulnerability to suicide-related morbidity among sexual-minority women is matched by parallel vulnerability among WSW for suicide-related mortality.”

“The findings of this study provide evidence that supports the existing literature that health inequities exist by sexual orientation, which can inform policy and program development in NC. Both LGB men and women had over 2.5 times the odds of ever having been diagnosed with a depressive disorder compared with heterosexuals. These findings are consistent with theories suggesting there is a health cost to having heightened levels of psychosocial stress from discrimination and stigma. Our finding of higher levels of cigarette smoking among LB women was consistent with previous findings. The health inequities found in our study among women are striking. LB women experience higher odds of chronic conditions when compared to heterosexual women. LB women had 3.5 times the odds of having a disability, and over twice the odds of ever having been diagnosed with COPD or asthma, and over 2.5 times the odds of being obese. Stress and obesity have been associated with asthma, which is consistent with the minority stress model, which posits unique stressors for LGB people. LB women had higher odds of ever smoking cigarettes and current smoking even after adjusting for age, education, and employment status (all of which were significantly related to current smoking in the general population). LB women also had greater odds of exposure to secondhand smoke at work and at home which could be associated with higher rates of asthma.”

“LGBT people comprise a population in need of suicide prevention efforts. Because access to firearms is associated with death by suicide, it is reassuring that in our study LGB respondents were significantly less likely than heterosexual respondents to report firearms in their homes. Transgender people may be even less likely to have firearms in the home than their non-transgender peers.”

“Foreign-born participants also reported higher levels of feeling unfair treatment by physicians than U.S.-born LGBT older adults. This disparity may point to the “double disadvantage” effect of being both sexual minority and foreign-born. LGBT older adults, particularly those in need of mental health services, often report discrimination in healthcare. Foreign-born individuals may face additional challenges in finding culturally responsive health providers. Further, discrimination and stress resulting from the increasingly anti-immigrant climate in the United States may exacerbate barriers to health-care access and contribute to greater feelings of unfair treatment… Foreign-born LGBT older adults also reported higher levels of individual-level barriers to accessing healthcare, particularly lack of trust in physicians, than U.S.-born participants.”

“Transgender people face multiple barriers within the healthcare system and frequently report delaying medical care due to cost, discrimination and harassment in healthcare settings, difficulty finding a healthcare provider, and denial of care. Being transgender was a legally acceptable reason to be denied insurance coverage until implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2010.”

“The reasons why men, and particularly bisexual men, are unwilling to disclose their sexual identity in a government survey require further investigation. However, the persistence of sexual stigma in Canadian society, despite the recent legal gains of LGB communities, likely plays a central role in men’s decision whether to disclose their sexual orientation… More so, willingness to disclose was influenced by age, HIV status, living environment, education, income, and ethnicity.”

“Gay/bisexual men had significantly lower mean BMI and lower prevalence of overweight and obesity than heterosexual men. Heart disease and hypertension prevalence was similar for both groups. Gay/bisexual men had higher prevalence of lifetime asthma and lower prevalence of diabetes than heterosexual men. Gay/bisexual men had higher education and income levels, were more likely to report having health insurance in the past 12 months, and were more likely to be White and less likely to be Hispanic or Asian than heterosexual men. Gay/bisexual men were more likely to be current smokers, and to report household smoking, but they were less likely to report food insecurity than heterosexual men.”

“Our core finding that gay and bisexual men who are classified as overweight or obese appear to have elevated likelihoods of chronic diseases may be better understood in the context of their exposure to minority stress… Additional mechanisms that contribute to the greater risk of chronic disease in sexual minority men may include behavioral and environmental factors such as diet, physical activity, and the built environment. Research findings concerning diet and physical activity among gay and bisexual men are mixed. One study found more physical activity and healthier eating habits among heterosexual men. In another study gay men reported less availability of fruits and vegetables in their communities and homes, and higher sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, whereas bisexual men reported more physical activity than heterosexual men. Another study found that eating patterns and physical activity levels were similar for men across sexual orientations and had an independent effect on BMI… Social norms, including concerns about body image, may be related to and/or interact with minority stressors, which in turn could result in higher likelihood of chronic disease.”

“Results of each of the logistic regressions examining participant demographic characteristics (i.e., age, relationship status, employment status, education level) and mental health outcomes (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms) as potential predictors of obesity across each of the six LGBT subgroups.”

“It is important to note that rates of overweight and obesity were troublingly high, with more than 50% of each LGBT subgroup reporting BMIs in the overweight/obese range, and more than one-fourth of each group (and up to 46.0%) reporting BMIs in the obese range. Recent national estimates place the U.S. obesity rate at 34.9%.1… The current findings also reveal significant variations in psychosocial correlates of obesity across LGBT subgroups. Namely, age, relationship status, employment status, and educational level emerged as being significantly related to obesity for some sexual minority subgroups but not others. In addition, depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms emerged as being significantly related to obesity for cisgender gay men only, with no psychosocial factors emerging as significant predictors of obesity for cisgender bisexual men, transgender women, or transgender men. Overall, these findings support the need for culturally tailored healthy weight promotion efforts within the LGBT community that incorporate the cultural realities not just of the LGBT community as a whole but also of distinct subgroups.”

“A higher proportion of participants who were older, had greater financial security, and with more stable housing status continued on the study than did those who were younger, who only sometimes or did not have money to cover basic needs and who had unstable or no housing.”

“In our analysis, older age was independently associated with being more likely to initiate PrEP, with the rate of initiation among men aged 40 years and older being four times higher than among those younger than 25 years… We also found that indicators of socioeconomic disadvantage (eg, not being employed, having unstable housing status, and having less or no money for basic needs), were associated with a reduced rate of initiating PrEP or being on PrEP… High-risk sexual behaviours such as condomless sex, condomless sex with two or more partners, group sex, and using non-injection chemsex-related drugs were also associated with PrEP use, indicating appropriate use of PrEP by these men. Similar to our findings, a recent national online prospective study in Australia reported that younger age, less use of illicit party or sex drugs, and lower engagement in HIV sexual risk behaviours such as group sex or any condomless sex, were independently associated with non-uptake of PrEP. The study also reported an increase in the uptake of PrEP from baseline (2014–15) to 24 months of follow-up.”

“Indeed, we found significant differences in awareness and interest in PrEP between provinces, even after adjusting for socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics. As funding models and interventions for PrEP are being considered across Canada, this research identifies populations that may benefit from additional PrEP education efforts or may face other individual-level barriers accessing PrEP… Increased willingness to pay for PrEP among respondents with higher SES, as well as increased awareness of PrEP among respondents with higher educational attainment, is consistent with fundamental cause theory—first articulated by Link and Phelan (1995).”

“The fact that educational attainment was positively associated with awareness and willingness to pay for PrEP out-of-pocket, but not with interest in PrEP, is consistent with fundamental causes theory: respondents with higher SES are more likely to know about, and have the means to access PrEP, despite being equally as interested in this health innovation as those with lower SES.”

“Younger age and lower educational attainment were associated with current tobacco use among sexual minority men and women, which is also consistent with previous findings among sexual minorities and the general population. Older participants were more likely to have quit using tobacco. However, in contrast to previous reports, higher educational attainment was not significantly associated with quitting tobacco for either sexual minority men or women. Previous studies found associations between education level and smoking status… Among sexual minority men in our sample, both alcohol and heroin use were each associated with increased odds of currently using tobacco… Among sexual minority men in our sample, alcohol, cocaine, and heroin use were each associated with a decreased likelihood of quitting tobacco. Alcohol use and frequent bar attendance have previously been identified as high risk situations for relapse among gay male smokers.”

“The disproportionate rates of tobacco use among gay and bisexual men intersect with the disproportionately high rates of tobacco use and smoking among people living with HIV. The intersection of these two health disparities represents a critical public health concern for sexual minority men also managing HIV, particularly as tobacco use has been associated repeatedly with worse HIV disease and treatment outcomes for sexual minority men who smoke or use other tobacco products.”

“As hypothesized, demographic, healthcare, and contextual variables were associated with smoking status. Demographic correlates (younger age, racial/ethnic minority status, lower levels of education, and income levels), replicated national trends of smoking behaviors among adults. Sexual identity also played a role in smoking: bisexual women were more likely than those who identified as lesbian or mostly lesbian to be current smokers. These results are consistent with the extant literature supporting elevated risk for smoking among bisexual women.”

“In addition to advice to quit, best practices for healthcare providers in helping to reduce smoking among their patients include linking patients to available smoking cessation treatments. Changes to policies and procedures at the level of the healthcare system can have a positive impact on assisting providers in offering smoking cessation services by identifying patients who smoke in the electronic medical record, by offering brief smoking cessation counseling training for all providers, by monitoring provider adherence to offering smoking cessation services to all patients, and by partnering with state-run quitlines to offer free services to patients.”

“The success of this program in increasing cancer screening among lesbians older than 50 suggests that a minority-specific intervention can increase positive health behaviors such as screening for cancer.”

“Not only are lesbians often invisible within the healthcare system, they also are less likely than heterosexual women to use preventive cancer-related screening services. A metaanalysis of seven large surveys completed from 1987–1996 (N = 11,876) demonstrated that lesbian and bisexual women were less likely than heterosexual women to undergo routine screening procedures such as mammograms and gynecologic examinations… For women who may put off health care for fear of having their sexual orientation discovered and recorded or because they have found hostility within the healthcare system as a result of their sexual orientation, the use of specialized educational programs is vital. For this minority group, simply identifying the women who comprise it is not enough; healthcare professionals, researchers, and educators must understand that some women belonging to this sexual minority may fear exposure. Many lesbians in this age group have encountered hostility from healthcare professionals and, thus, are reluctant to seek health care. In addition, many of the screening programs do not have culturally appropriate materials designed to appeal to women who are intimate with other women.”

“Overall, transgender respondents reported poorer health and increased days of activity limitation. Some of the largest disparities faced by transgender respondents are seen in substance use and mental health… Current substance use was also elevated among the transgender sample. Nearly one third of transgender respondents reported using marijuana and one-fourth reported binge drinking in the past 30 days.”

“There is now a body of work identifying barriers and facilitators to older LGBT+ people accessing care and support services. However, less is understood about ‘healthcare stereotype threat (which) is the threat of being personally reduced to group stereotypes that commonly operate within the healthcare domain’… This is particularly in relation to older LGBT+ people who are known to avoid healthcare services due to concerns about prejudice and discrimination. Increased knowledge could improve healthcare professional’s competency and confidence, resource allocation, inclusion in healthcare education and developing a standard/quality framework for training.”

“YMSM appear to engage in more instances of substance use and sexual risk behaviors as they age… Increased impulsivity and psychosocial stressors, including the potential challenges of coming out and negotiating a stigmatized sexual identity, make emerging adulthood an acutely vulnerable developmental stage for YMSM. Additionally, increased substance use and sexual risk behaviors may be associated with myriad health-related concerns, including depression and intimate partner violence… In general, drug use variables were positively and significantly correlated with one another, suggesting that participants who reported more frequent use of one drug (e.g., alcohol to intoxication) also reported more frequent use of other drugs (e.g., marijuana, inhalants, and other drugs). Similarly, the condomless sexual activity variables were strongly and positively associated with one another, again suggesting that more frequent engagement in one activity was related to more frequent engagement in other unprotected sexual activities. This pattern was evident across time. The pattern of correlations among the drug use variables and sexual activities differed across assessments. In general, however, more frequent use of alcohol and drugs was positively associated with higher levels of condomless sexual activity… A critical finding of our investigation is that the association between drug use and condomless sex does not differ by race/ethnicity. This builds upon our earlier reports from this cohort study that show that Black YMSM, who are most affected by HIV in the United States and in our study, do not engage in more sexual risk behavior than their White peers. Moreover, similar findings are indicated for drug and alcohol use; any differences that do emerge are attenuated in light of socioeconomic status. Such findings support the notion that behavior in and of itself, is insufficient in explaining HIV prevalence in the Black population, supporting the work of other. Social and structural factors, including poverty and more limited access to quality health, which may lead to more untreated and unmanaged HIV infections within the population and greater psychosocial burdens which may engender risk, provide a clearer explanation of the drivers of these epidemiological patterns… To this end, medical practice focused on gay men’s health must understand HIV in this context, with attention to the synergy that exists between drug use and sexual risk and also the numerous other health burdens young sexual minority men face including violence and mental health burdens, and finally within socio-political-economic circumstances of the time.”

“As in the original analysis, significant (p<0.01) differences were found in regards to education, income, systolic blood pressure and history of hard drug use. The revised categorization revealed that income and education levels were the highest among Gay men and the lowest among Bisexual men, and that Gay men were more likely to have a history of hard drug use than Heterosexual men, but were less likely to have a history of hard drug use than Bisexual or Homosexually-experienced Heterosexual men. Systolic blood pressure was lower for both Gay and Homosexually-experienced Heterosexual men compared to Heterosexuals, but there was no significant difference for Bisexual men.”

“Our results indicate that certain subgroups of SMM are at increased risk for CVD compared to Heterosexual men, and this increased risk cannot be completely attributed to differences in demographic characteristics or negative health behaviors. Specifically, we found that Bisexual men were at significantly increased risk for CVD and Homosexually-experienced Heterosexual men were at significantly decreased risk for CVD compared to Heterosexual men. Gay men did not exhibit significantly increased CVD risk compared to Heterosexual men after accounting for differences in education and history of hard drug use. These findings indicate that it is critically important to look at differences within sexual minority categories, as combining Gay, Bisexual and Homosexually-experienced Heterosexual men into one broad category may mask important differences… Future work is also needed to elucidate the mechanisms by which sexual minority status confers increased CVD risk and, in particular, how these mechanisms may differ among sexual minorities and by gender.”

“Age cohort was found to significantly impact the likelihood of gay men utilizing health services where older gay men were seen to access medical care less often when compared to both younger cohorts. When comparing to older gay men, middle-aged gay men were more likely to have sought medical care in the past 12 months. Additionally, younger men were more likely to have sought medical care in the past 12 months compared to older men.”

“A factor commonly attributed to the physical health disparities among gay men is the avoidance of health-care settings. Avoidance of health-care systems refers to a lack in receiving health-care services due to a specific phenomenon such as the presence of real or perceived stigma… Internal stressors may emerge in the form of internalized homophobia, expectations of rejection or discrimination, and/or concealment of sexual identity as a result of stigma and discrimination felt by individuals… Middle-aged men, due to their experience of coming-of-age during or shortly after the AIDS epidemic, may relate to their higher likelihood of seeking care more regularly… Younger men may have sought medical care more often than older men for services such as HIV/STI testing or HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consultations which are heavily advertised to this younger generation who did not personally live through the AIDS epidemic.”

“A person’s mental health, likelihood of disability, and functional ability in later life can be related to lifetime exposure to discrimination, lack of social support, and poverty, as well as having lower educational attainment. Consequently, groups that experience disadvantage in these areas may demonstrate poorer health at earlier ages, accelerated aging, and earlier mortality compared to their more advantaged peers… Compared to heterosexual women, sexual minority women face greater risks for mental health problems such as depression, frequent mental distress, and greater tension or worry due to the marginalization, discrimination, and stigma they face in the broader social environment.”

“Some surprising results appeared in relation to how race/ethnicity moderated health disparities. Although race/ ethnicity was not hypothesized to moderate relationships to mental health outcomes, findings suggest that sexual minority women of color were less likely to experience frequent mental distress than white sexual minority women. For some functional health dimensions (activity limitations and use of special equipment), sexual minority women of color also reported better health compared to white sexual minority women.”

“The validity and reliability of measures can be affected by many factors, including race, ethnicity, immigration status, age, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. For example, a study of American Indian adolescents, using questions to assess sexual orientation first tested in a general sample of Minnesota adolescents, found a higher nonresponse rate than was found in the Minnesota sample… A coordinated and thoughtful approach to adding sexual orientation variables to existing data systems, as recommended above, could take many years. However, if the activities outlined above are undertaken, the 29 objectives addressing health disparities based on sexual orientation in Healthy People 2010 will be appropriately monitored. DHHS can then undertake the activities necessary to eliminate health disparities. Of course, if the above activities are undertaken, the monitoring of Healthy People 2010 will only be one valuable outcome. More important, the overall health of LGB people will be assessed and for the first time, providers and researchers concerned with the health of these populations will be able to raise awareness and acquire the necessary resources to address important health concerns.”

“There were significant racial/ethnic differences in health-promoting and health risk factors. African Americans showed a higher level of lifetime LGBT-related discrimination when compared with non-Hispanic Whites, although Hispanics did not. Race/ethnicity was not associated with lifetime LGBT-related victimization or day-today discrimination. When compared with non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans and Hispanics had lower levels of household income, educational attainment, identity affirmation and social support, and higher levels of identity stigma and spirituality.”

“As hypothesized, lower socioeconomic resources, including income and education, were reported by African American and Hispanic LGBT older adults compared with non-Hispanic Whites. Both income and education mediated the relationship between racial/ethnic minority status and poorer physical and psychological HRQOL, a relationship well documented in racial/ethnic health disparities research… Recognizing identity affirmation as a significant factor in both physical and psychological HRQOL provides an opportunity to support individuals’ positive identity appraisal as opposed to solely challenging sexual identity stigma. Additionally, supporting the development of personal spiritual resources and creating safe and affirming spaces for spiritual development may further promote HRQOL among LGBT older adults of color. Future interventions should be tailored to promote the development of supportive social networks available to LGBT older adults of color including close family relationships and broader and more inclusive racial/ethnic and LGBT communities.”

“While immigrants tend to have better health than native born individuals when arriving to the United States, a phenomenon commonly referred to as the immigrant health advantage, the health advantage tends to deteriorate with time. Hence, immigrants with longer residence in the United States are at increased risk for poor health and chronic disease development. Several migration-related processes and mechanisms such as acculturation, stress from adapting to new environments, and socioeconomic disadvantage have been suggested as explanations for this health decline over time. Moreover, barriers to health-care access and sociopolitical challenges associated with immigration status may exacerbate health disparities among the immigrant population. Older adult immigrants have complex health needs that are associated not only with the aging process but also with social, political, economic, and cultural factors that can shape health-care access, health-related behaviors, and outcomes.”

“Among structural-level barriers in the adjusted model, foreign-born LGBT older adults reported higher mean frequencies of not having the care needed available in their area (M: 1.58 vs. 1.27; p < .05), not having transportation to care (M: 1.60 vs. 1.20; p < .05), and experiencing unfair treatment by physicians (M: 1.65 vs. 1.44; p < .05). Foreign-born LGBT older adults also reported higher mean frequencies of lack of access of LGBT friendly healthcare than U.S.-born LGBT older adults in the unadjusted model (M: 1.69 vs. 1.39; p < .05), but the difference was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for covariates… As poverty and education are well-established social determinants of health, foreign-born LGBT older adults may encounter greater challenges to good health than their U.S.-born counterparts… Higher levels of not having needed care available in the area among foreign-born LGBT older adults may be attributable to several factors, including the unique health-care needs of the foreign-born population.”

Transgender and Gender Non-Binary Health:

“The transgender population is one of the most medically underserved populations and faces significant disparities accessing gynecologic health care services. Transgender men have lower rates of cervical cancer screening and Papanicolaou (Pap) tests, and one study documented that transgender male patients had 37% lower odds of being up to date on Pap tests compared to cisgender women… These health disparities also vary geographically. Research shows that living in a rural setting can increase the likelihood of isolation and discrimination against the transgender population.”

“We found significantly lower rates of contraception use and cervical cancer screening in our population compared to national rates and no significant difference in utilization based on health insurance type… Our population is unique, as 92% were insured and <3% were uninsured, suggesting that no matter how robust the insurance coverage, transgender and gender diverse individuals still face health inequities… Transgender individuals living in rural areas often experience increased stigmatization by health care providers, leading to avoidance of seeking health care services due to fear of discrimination."

“Surveys show that up to 70% of health care providers report unfamiliarity with screening recommendations for transgender individuals, which is, in part, due to lack of health maintenance guidelines specific to transgender patients. Moreover, this may lead to low-quality care and poor recommendations… Similarly, health maintenance screening in transfeminine individuals, status post-vaginoplasty, is another area of ambiguity. While these individuals are not at risk for cervical cancer, they are at risk for HPV and other sexually transmitted infections. In our cohort, few transgender women who underwent vaginoplasty had a documented pelvic examination over the past year and none had documented Pap testing. Review of provider notes revealed two cases of providers documenting: “Pap does not apply because no cervix present.” However, a study conducted in the Netherlands tested neovaginal swabs for HPV in transgender women and discovered that 20% of sexually active transgender women tested positive for high-risk HPV compared to zero percent of sexually inactive transgender women. It is imperative that formal guidelines also be established for HPV screening in transgender women who undergo neovaginal reconstruction… Our study also highlights areas in which physicians provided erroneous recommendations to transgender and gender diverse patients. In two cases, providers documented counseling transmasculine patients that testosterone therapy alone provides adequate contraception, although previous reports have proved this to be false.”