Shutting Down Skin Cancer

Melanoma is commonly caused by the damaging effects of ultraviolet light—from sources like sunlight and tanning beds—on the DNA of skin cells. This UV damage can activate genes that encourage precancerous cells to further mutate into full-blown skin cancer. At the same time, UV damage can turn off other genes that would normally prevent tumor growth. With enough wrongly flipped switches, cancer can flourish. And melanoma is certainly flourishing. This year alone, 96,480 new instances of melanoma will be diagnosed in the United States and 7,230 Americans will die from the disease.

With so many people affected by melanoma, scientists are on the hunt for better ways to screen for melanoma risk and treat the most lethal types of skin cancer. One particularly voracious type of melanoma, caused by mutation of a gene called NRAS (which instructs cells to produce a protein of the same name, NRAS), drives 25 percent of skin cancers.

“There are immunotherapies and targeted therapies that have shown huge improvements for patients with melanoma,” says Rutao Cui, a Boston University School of Medicine professor of pharmacology and dermatology. “However, for patients with NRAS mutations, they don’t have very useful or very effective treatment strategies.”

Now, an international research team led by Cui has discovered a new way to stop the progression of melanoma by NRAS mutations with the flip of a genetic switch. Their findings were published in Cell January 31, 2019.

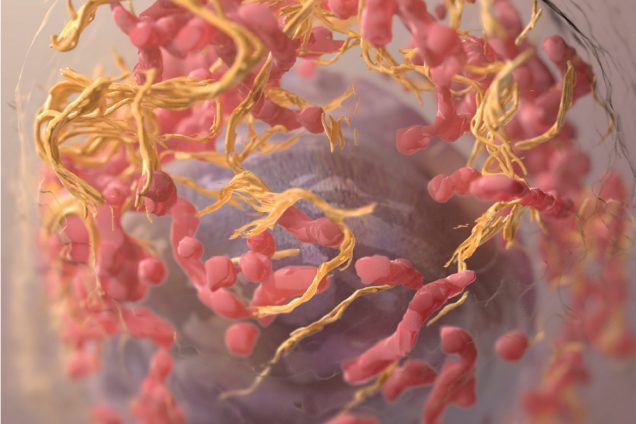

Inside our bodies, proteins like NRAS play the role of dominoes, interacting with one another to switch other important gene activities on or off. The researchers set out in search of a way to interrupt the process by which mutated NRAS can instigate the growth of skin cancer. Since targeting the NRAS gene—just one of several dominoes in this type of skin cancer pathway—has proven to be so difficult, the researchers were determined to find another approach.

For NRAS to trigger cancer development, it first needs to be activated by another protein in the body. Until now, it’s been unknown exactly which protein is responsible for activating NRAS. But after testing the effect of several different proteins on the activity of NRAS, the team zeroed in on a likely culprit, a protein by the name of STK19.

STK19 is not a newly discovered protein, but its purpose has not been known until now. Cui’s team found that STK19 appears to work as an “on” switch for NRAS—activating production of NRAS proteins, which in turn trigger the toppling of several other genetic dominoes downstream.

The researchers also found that unlike with NRAS, they could disable the STK19 gene and greatly diminish its ability to set the skin cancer sequence in motion.

Together, the team designed a new drug compound to shut down the effect of STK19 on NRAS. Then, testing its effect on skin cells cultured in petri dishes and in animal models, they proved that their compound can block NRAS activation and prevent melanoma from developing.

Cui says that this result is exciting not just for melanoma, but for other cancers as well. While the relationship between STK19 and NRAS may be particular to skin cancer, the approaches the team used to identify and block key activating proteins can be applied to find new treatments for similarly difficult-to-cure cancers.

Now the research team is looking to take their research to clinical trials to test the STK19 inhibitor in humans, and hopefully, someday make it available as a targeted therapy to combat NRAS-driven melanomas.

In the meantime, Cui says, much work still needs to be done to not only create better and more precise treatments for patients suffering with melanoma, but also to alert vulnerable populations about the risk factors associated with the cancer.

“We need more monitoring for early diagnosis and full-body examinations for problematic spots,” he says, “and more proactive strategies for patients [at the highest risk of developing melanoma] to prevent cancer progression and metastasis.”

This work was supported by Boston University, the National Key R&D Program, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China, the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities, and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research.

This BU Today story was written by Sarah Wells (COM’18).