Never Smoked. Lived Right. Died of Lung Cancer. The Puzzle of Cancer in Nonsmokers.

Avrum Spira’s aunt died of lung cancer almost 20 years ago. She was a nonsmoking exercise buff in her 40s who hadn’t been exposed to any known toxins; she worked in a government office, not a coal mine. “One of the healthiest people you could imagine, did everything right,” says Spira (ENG’02), who at the time was an internal medicine resident at the University of Toronto.

The one thing she didn’t do right wasn’t her fault: she’d been born to a nonsmoking mother who had died from the same illness. “I’m absolutely convinced she had a genetic predisposition” to lung cancer, says Spira, a School of Medicine professor and chief of computational biomedicine. That conviction set him on a quest for the genetic key to a medical mystery: why some people who have never smoked fall victim to this scourge of cigarette users.

Lung cancer kills more Americans than any other cancer, and twice as many women die from it than from breast cancer, although the latter gets greater public attention, says Spira. In 2008, the last year for which data was available, more than 208,000 Americans were diagnosed with lung cancer and almost 158,600 died from it. Spira says between 10 and 15 percent of these annual victims are nonsmokers (the percentage has been edging up slowly in recent years) with no apparent exposure to other toxins—a crucial caveat. “How do you know someone has been or has not been exposed to something in the environment?” he asks. Some potential toxins, like radon, are invisible, he notes, “so people who we’re seeing now, with higher rates of nonsmoking lung cancer—is it because they were exposed to radon 20 years ago?”

It’s true that worldwide, the rise in the incidence of lung cancer —from the eighth leading cause of death in 1990 to fifth in 2010—is mostly a function, perversely, of good news: as living standards have improved in the developing world, more people survive into adulthood, meaning a decline in childhood deaths from malnutrition and infectious diseases. That has brought an accompanying uptick in the number of people dying from diseases mostly found in wealthier countries, among them cancer. Moreover, air pollution in industrializing countries has resulted in more lung cancer in nonsmokers there, Spira says.

But in the United States, he says, doctors believe there’s a similar spurt in lung cancers in nonsmokers who’ve had no apparent contact with other toxins. The most extensive studies, incorporating detailed questionnaires and visits to peoples’ homes to see their environment, show that “there hasn’t been a clear association among nonsmokers who are getting lung cancer with exposures to other things.”

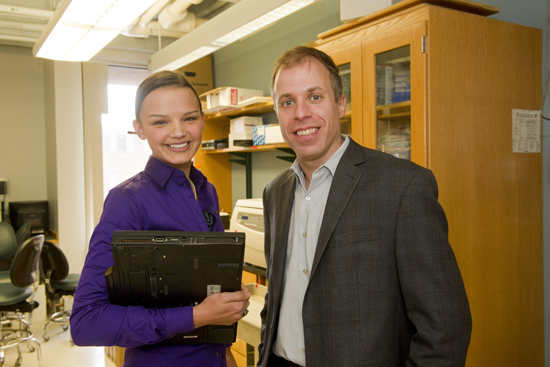

An ongoing, as-yet-unpublished study by a team that includes Spira is looking at tumor tissue and adjacent, noncancerous tissue from the lungs of 32 subjects with lung cancer: 8 smokers, 11 former smokers, and 13 who never smoked and had no apparent exposure to other toxins. The researchers ran the samples through a gene sequencer at MED, which “can give us unprecedented insight into the genomic changes leading to lung cancer” in nonsmokers, says Rebecca Kusko (MED’14), a graduate student spearheading the study in Spira’s lab.

With the sequencer, “we study the normal cells from each person as a control,” says Spira, “and then what happens in their tumor right next door, and say, what’s changed?” Preliminary results suggest that in the smokers, “a huge number of cancer pathways are activated,” as genes controlling cell growth in the tumors turned on. But those pathways weren’t necessarily activated in the nonsmokers, who showed different gene changes between their healthy lung tissue and their tumorous tissue. The researchers’ hypothesis is that the nonsmokers had a genetic predisposition, a pathway, to cancer that was activated by something in their environment.

That trigger, Spira theorizes, may be a viral infection (cervical, liver, and head and neck cancers are all caused by viruses, he says). The researchers are now sequencing the tumor tissue of the nonsmokers to try and find any viral genes. “Even if there’s one viral gene per million human genes, we might pick it up, we believe,” he says. The work will take a year or two.

Potential therapies—which are many more years away, he warns—might include screening people with the genetic predisposition and then giving those with the predisposition regular lung scans to catch cancers early. Another possibility would be drugs that could turn off uncontrolled growth in cancerous cells. (Spira got attention in 2010 for research suggesting that the natural compound myo-inositol could turn off incipient lung cancer in smokers.)

Those who walk Commonwealth Avenue and have to dodge fumes from smokers on break may wonder about secondhand smoke. Research is mixed, but Spira, who researches the amount of smoke necessary to change gene expression and possibly lead to lung cancer, believes that it takes a big dose—perhaps exposure over months or years.

Almost half a century after the surgeon general first warned of smoking’s dangers, Spira says that even Hollywood is catching on that not all cancer victims heedlessly bring the disease on themselves. In 2011, he was a presenter at the Prism Awards, given for accurate portrayals of illness in entertainment media. He handed an award to an actress whose character on the soap opera The Bold and the Beautiful had lung cancer.

The character was a nonsmoker.

This BU Today article was written by Rich Barlow. He can be reached at barlowr@bu.edu